This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

In school grading terms, Mountain View Elementary is a B school.

Based purely on demographics, the school in Salt Lake City's Glendale neighborhood should be getting a D, or even an F.

Mountain View is one of the most diverse and economically impacted schools on the Wasatch Front. The vast majority of its students — 87 percent — are racial or ethnic minorities. And 94 percent live in low-income households. Normally, those factors would indicate a lower overall grade for the school.

Instead Mountain View is an outlier, bucking conventional wisdom and its own demographic destiny.

"We don't necessarily look at that as a deficit," Principal Kenneth Limb said of Mountain View's demographics. "We have great diversity here."

Other majority-minority, economically disadvantaged schools fall into a more discouraging pattern: Students living in poverty or with limited knowledge of English perform worse in school than their affluent, native English-speaking peers.

An analysis of school grades and PACE reports for Wasatch Front school districts shows a general connection between high-diversity and low-income school populations and lower school grades. The grades are based on students' year-end test scores in math, English and science, graduation rates and ACT scores.

Among the Ogden, Davis, Salt Lake City, Murray, Jordan, Canyons, Granite and Alpine school districts, A- and B-grade schools were more likely to have low levels of poverty and racial diversity than schools with D's and F's.

In those eight school districts, no school with an A had a minority population greater than 35 percent of its student body. And no F-earning school had a minority population smaller than 37 percent.

Critics of Utah's newest system of school grades argue that they simply document and reinforce Census tract or ZIP code data: Higher-income, less diverse schools get better marks.

But Mountain View Elementary — and a handful of other outliers — give the grading system's mastermind, Utah Senate President Wayne Niederhauser, reason to hope. The Sandy Republican sponsored the 2011 legislation establishing the state grading system. The grades, he says, reflect more than income and diversity.

"There is an argument out there that school grades are an indication of your ZIP code and that is not true," Niederhauser said. "The information that school grading is giving us is helping make positive changes."

He maintains the grades help identify successes at schools like Mountain View that buck demographic trends, which can then be replicated throughout the state.

"They're not anomalies," Niederhauser said. "They're doing things that other schools aren't doing."

—

Best Practices

Limb knows his school's demographics affect student performance, but he considers Mountain View's profile a strength.

He describes the school's diversity as "funds of knowledge." Students benefit from a school environment filled with different cultural backgrounds, he said, and as long as children are making progress, parents are satisfied.

"School grading is a political thing," Limb said. "If you ask our parents what our school grade is, they will not know and most of them won't care."

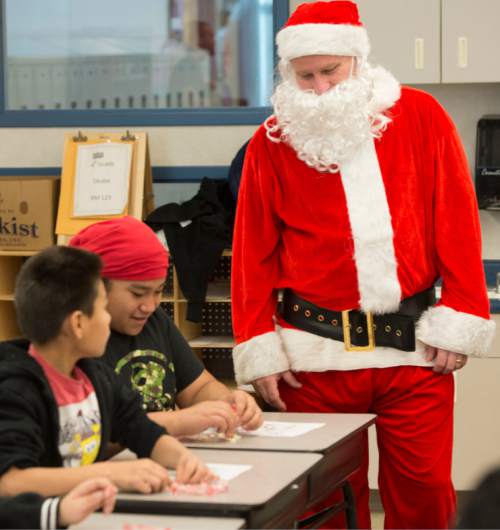

More than 20 languages are spoken at Mountain View, Limb said, and many students are refugees who only recently arrived in the United States.

Each kindergarten class is staffed with an assistant, in addition to the teacher, to help with children who start school behind their peers. And small groups of struggling students are regularly pulled aside for individualized instruction.

"I hesitate to say we're doing well," Limb said. "We have a long way to go."

But Mountain View is not the only diverse, low-income school to buck demographic trends.

If the Salt Lake City elementary is an unexpected outlier, Ogden's Horace Mann Elementary sticks out like a sore thumb.

With 67 percent of its students living in low-income households, the school is not only the poorest A school analyzed by The Salt Lake Tribune, its demographic profile stands out from that of other A-earning schools, where poverty rates hover in the low teens to mid-30 percent range.

Principal Ross Lunceford said the school's demographics correlate with higher numbers of families in crisis and single-parent households. It also means that a student at Horace Mann is less likely to have the kind of at-home resources, from reading materials to Internet connectivity, that benefit other students.

But those factors, Lunceford said, are not insurmountable.

"In Ogden, we truly believe that our schools, even though they're highly impacted, can succeed," he said. "Our goal was to be on top of the pile, wherever the pile ended up."

Teachers at Horace Mann meet weekly in grade-level teams. The groups ease collaboration between colleagues and provide a setting to review individual student performances and develop strategies to help struggling kids.

That type of teamwork and performance review is common in Utah schools, including those at the bottom of the school grading curve, and Lunceford said success comes from the personnel a school has in place.

"The staff makes the school," he said. "You can have all the right things in place and you've got to have the right people along with that."

Todd Theobald, the principal of another outlying school, Majestic Elementary in West Jordan, echoes that theory. He watched his school go from "literally one point away from an F" to a B in the most recent grade reports. Nearly two-thirds of students at the school, 61 percent, are racial or ethnic minorities, and 77 percent are low income.

Roughly half of the students at Majestic are learning English as a second language and Theobald said it's clear that his students do not have the advantages of more affluent students in Utah, whose parents have college degrees and arrive in kindergarten ready to learn.

"To pretend like poverty doesn't impact a school is just ridiculous," he said. "This myth that (demographics) are not going to make a difference, which is what political people say, it's just not true."

After last year's school grades were issued, Theobald said, he and his staff focused on incremental steps instead of the steep climb ahead of them. They ignored the enormity of universal proficiency and focused on teaching a few things really well.

Each month teachers would pick three standards from the Utah Core for their grade level, and make sure students mastered those standards.

"By doing that, we started seeing kids making progress," he said. "And then success motivated more success."

What the public sometimes overlooks, and what school grading fails to show, Theobald said, is the disparate circumstances that exist for students outside the classroom.

In sports terms, school performance reports often focus on the finish line, he said, without acknowledging how different the starting points can be.

"What it means for Majestic to be a B is very different from another school," he said. "That's the subtlety that we understand as educators that parents don't."

—

Extra Resources

The outlier schools have more than strategy boosting their grades.

Like many high-performing, low-income schools in Utah, Mountain View, Horace Mann and Majestic all are Title I schools. They receive supplemental funding from the federal government to offset the challenges of a low-income population.

That funding translates into hiring more staff and reducing class sizes, providing additional training for teachers and investing in targeted intervention programs for struggling students.

Last year, Horace Mann received roughly $81,000 in Title I funding, Majestic got $700,000 and Mountain View received $342,000, according to Utah State Office of Education records.

All three elementary principals said those extra resources played a role in their school's relative grade success.

"We need it," Limb said.

Any school with a low-income population of 75 percent or higher must be designated as Title I, said Ann White, director of federal programs for the state.

But for schools below that threshold, it is up to the school district to determine how many slices to take from the pie of Title I funding.

"Canyons and Jordan (school districts) choose to serve fewer schools so they can give them more dollars," White said.

She urges caution when discussing how demographics help or hinder school performance.

It's important to remember that minority and low-income students are not less intelligent than their white, affluent peers, White said. At the same time, educators have to acknowledge the challenges that some students face.

"It's not the capability of the student by any means," she said. "It has to do with lots of external factors."

It helps to consider Utah's refugee population, White says, with students often placed in school mid-year with little or no English literacy and no familiarity with the American schooling system.

"English language learners struggle, as I would," she said. "Drop me into Russia, or into a Mexican school, and say, 'You've got a year to learn Spanish' and I'd have to work really hard to do so."

—

Making the Grade

Utah is in its second year of school grade reports. While critics say the system is a shallow measurement of what goes on in a school or educators' efforts to help students, state lawmakers still back their strategy for gauging school performance.

Low grades carry a stigma of failure that is disheartening for teachers who feel they're doing their best, said Sandy Jorgensen, an instructional coach at West Valley City's Monroe Elementary.

Her school received a C grade this year, but is also one of the most economically impacted schools in the Granite School District.

"We want to get higher," she said. "Sometimes it's difficult for teachers who are working so, so hard."

Meanwhile, administrators at the outlier schools say they will continue to build programs to target help at struggling students, whether or not they agree with the state's grading system.

"I don't put a lot of weight in them, but we don't dismiss it," Lunceford said.

Theobald said his staff recently helped a family find housing, and throughout the year, the school is involved in non-academic programs aimed at supporting low-income families.

Those efforts may not directly translate into higher test scores, he said, but it's unlikely a student will have the at-home support they need when they're living out of a car.

"There's so much work that we're doing that will never be measured by a school grade that's making a life better and helping kids be able to focus on education," Theobald said.

Niederhauser, however, considers the program a success. The grades, he said, have led to discussions about how to improve student performance, and policymakers are learning from the results.

The Utah Senate president acknowledged that many of the state's success stories are Title I schools that receive supplemental funding. He is currently working on a bill that would provide Utah's worst-performing schools with extra resources and training for principals.

"We're not just going to leave these folks hanging," Niederhauser said. "We're going to try to give them support now to help bring their grades up."

It's unlikely that any accountability system could paint a full, perfect portrait of school performance, he added. But school grading rightfully focuses on outcomes.

Without an accountability system, he said, a school could hide its failings behind the successes of specific programs, like International Baccalaureate or Advanced Placement, while every year failing to prepare the majority of students for life after high school.

"It may not tell the whole story, but it tells the most important story, and that's the end results," he said.