This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

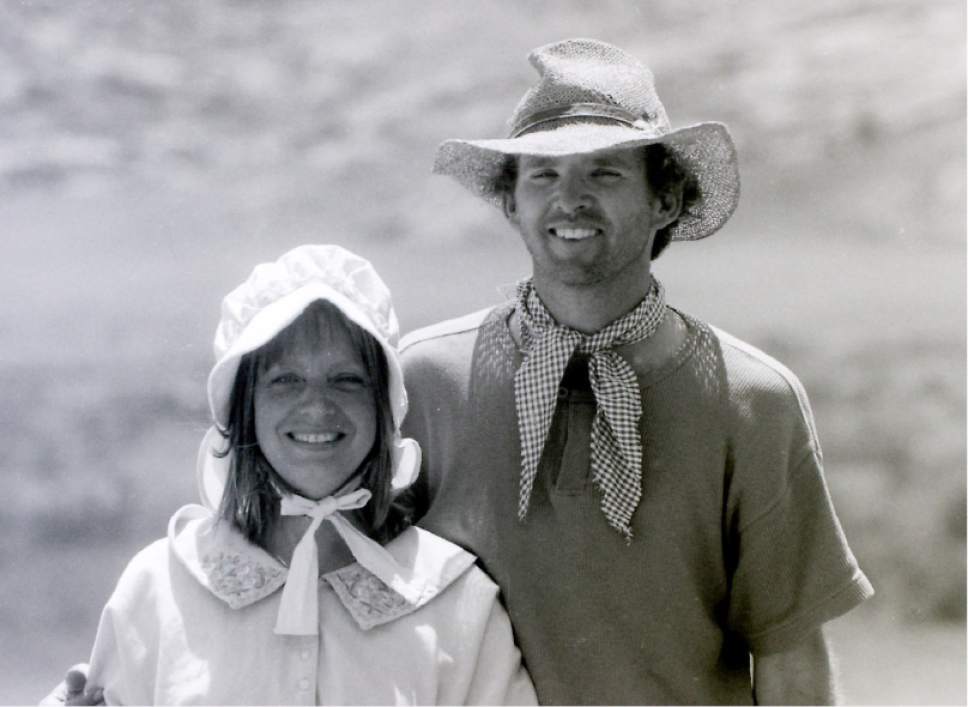

It takes a certain kind of person to don King Arthur attire and joust in public parks, show up in gray or blue uniforms for reimagined Civil War battles, or walk 1,000 miles in droopy sunbonnets and long skirts as a Mormon pioneer.

I am not drawn to such re-enactments — especially not the trekking kind.

Growing up in suburban New Jersey, I share Woody Allen's view that nature is lovely, "I just don't want to get any of it on me."

So when my editor told me in 1996 that a band of Latter-day Saints was planning a trip across the Plains in covered wagons or pulling handcarts for the 150th anniversary of the epic Mormon journey and that our paper would be covering it every day for three months — and that I would be among three reporters chronicling the experience — I thought he had lost his mind, or at least all editorial judgment.

But there I was a year later, bouncing around the back of a covered wagon in my Deseret Industries skirt — borrowed bonnet on head and reporter's pen in hand — as we snaked across the flats of Nebraska and the rocks of Wyoming before soaking in the cheers from a throng of 50,000 well-wishers at This Is the Place Heritage Park.

"This is beyond my wildest imagination,'' said Midway resident Linda Whitaker, viewing the crowds.

The emergence of the wagon-trainers from the mouth of Emigration Canyon at 11:30 a.m. on that scorching July morning in 1997 was the crowning moment of a 97-day odyssey that captured media attention from New York to London to Paris.

Television stations and newspapers were irresistibly captivated by the image of horse-drawn wagons, walkers and cart-pullers trudging unceasingly through dust, mud, wind, heat, rain and snow for 1,080 miles in contemporary America — like Amish on the move.

Even then-President Bill Clinton congratulated the travelers, saying in a letter, "The story of the Mormon pioneers ... is the story of everyone who has ever traveled to our shores seeking freedom to worship according to the dictates of their own conscience.''

LDS Church President Gordon B. Hinckley was on hand that day to salute the sesquicentennial procession.

"The picture greeting you today is different from what it was in 1847,'' Hinckley told those who gathered at the foot of a monument marking the spot where Brigham Young is said to have declared, "This is the right place.''

These days, the amiable late Mormon leader said, "thousands of automobiles travel paved roads, airplanes thread the skies. But with all of this, I see we may have lost something that you have become reacquainted with.''

And it was that something that attracted — by the end — some 10,000 participants, whether for a day, week or the entire span. There were Mormon nostalgists and secular history buffs. There were business professionals, ranchers, hairdressers, writers, restaurateurs, homemakers and teachers. They came from Japan, Austria, Canada, England, Australia and New Zealand. The youngest walkers were grade-schoolers; the oldest rider, 86.

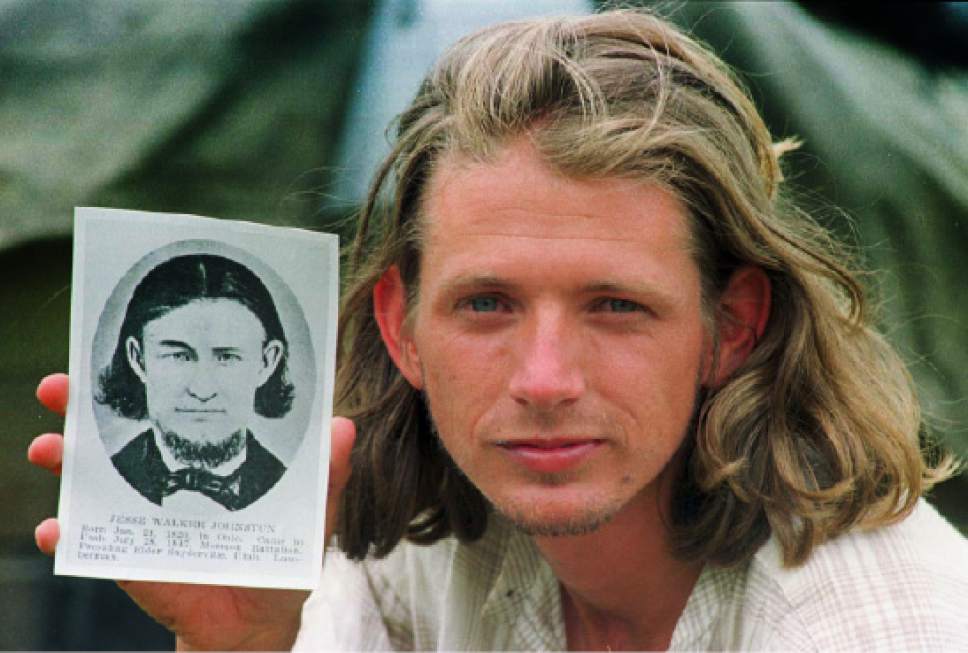

We gave cellphones to Whitaker and her husband, along with Joseph Johnstun of Salt Lake City, and Leon Wilkinson of Bloomfield, Iowa, so they could call in daily reports from the trail.

The assignment turned out to be one of the most meaningful and memorable of my professional career and where I came face to face with the darkest moments of my personal past.

—

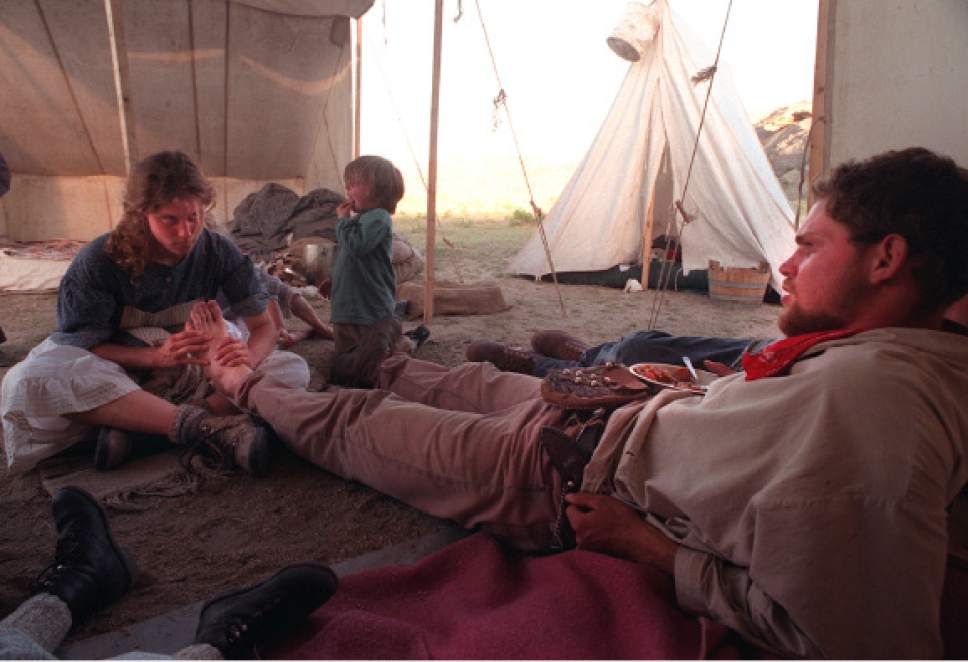

Alternating centuries • Each day, about 200 wagon riders, walkers and handcart pushers arose well before dawn to the persistent clanging of a big iron triangle. They dressed hurriedly, struck the tent or straightened the wagon, brushed their teeth and lined up for breakfast, usually oatmeal and orange juice. Then came the morning meeting, which began with the Pledge of Allegiance and a discussion of the day's route.

With a cry of "Wagons Ho," the train was on the trail by 7 a.m., covering between 10 and 30 miles a day. Those who could not walk the whole way could jump on a bus known as the "sag wagon.'"

At night, the wagons usually would circle, surrounded by tents, horse trailers and finally the 300-plus support vehicles — campers, RVs, cars and trucks.

Some participants, including docents from This Is the Place — known as the authentic group — tried to replicate the pioneer experience as closely as possible (though members carried their gear in trucks and campers). They wore shirts with wooden buttons (no zippers), ate potatoes and beans, slept in 19th-century tents, churned butter and passed the time square-dancing and reading.

Even the most determined travelers, however, had trouble leaving the 20th century behind. Floppy straw hats on heads, Nikes on feet. Thickly braided hair covered multiple ear piercings. Journals kept on laptops. Portable toilets, mosquito repellent, sunscreen, garbage bags and painted toenails.

No matter how many conveniences the modern-day pioneers packed for the three-month trek from Winter Quarters, Neb., to Salt Lake City, it was still physically and emotionally arduous.

—

Agony of loss • I had never seen wilder winds — blowing meals off paper plates and collapsing our sturdiest tents — than when I took my reporting stint in Wyoming. Nor such wide-open spaces or a bigger sky.

I walked beside the long-termers and day-trippers to report their experiences by day and then camped with them at night, listening to the yarns about what had happened there back in the day.

Independence Rock was the site of some tragic events.

Having found no water for miles and miles, the exhausted Mormons arrived at the nearby Sweetwater River, eagerly plunging their buckets into what they presumed was fresh water for their families and animals, only to discover it was swimming with cholera. Many perished.

Suddenly, I felt a jolt of recognition. I'd heard this story from my grandmother many times before but had no picture of where it had happened.

My ancestor Jedediah Grant was in one of the first companies, and his 6-month-old daughter, Margaret (my name, too), contracted the fatal disease, died and was buried near the giant hill of stone and grass.

Days later, Grant's wife, Caroline, also lost her life to the waterborne disease. He constructed a casket and brought her to Zion for burial. Her dying wish was that he do the same for their baby. But when Grant returned, the shallow grave had been ravaged by wolves. No body could be found.

I, too, buried a child, but can visit her well-cared-for resting place in the Salt Lake City Cemetery anytime I want. We have photos and videos to supplement our thoughts of her, cementing her image.

Many of our ancestors had only memories of lost children, growing distant with every passing day.

As I sat weeping under Wyoming's starry night, I thought maybe that's why people immerse themselves in these historical events, rather than just reading about them.

Sacred rituals including Hanukkah, Passover, Ramadan and the Christian Passion Week all symbolically celebrate events from the past — as acts of vicarious empathy for ancestors.

Not a bad thing for a religion writer to learn.

Twitter: @religiongal

Correction: July 25, 11:25 a.m. • Jedediah Grant was in one of the first pioneer companies. An earlier version misstated which group he was in.