This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

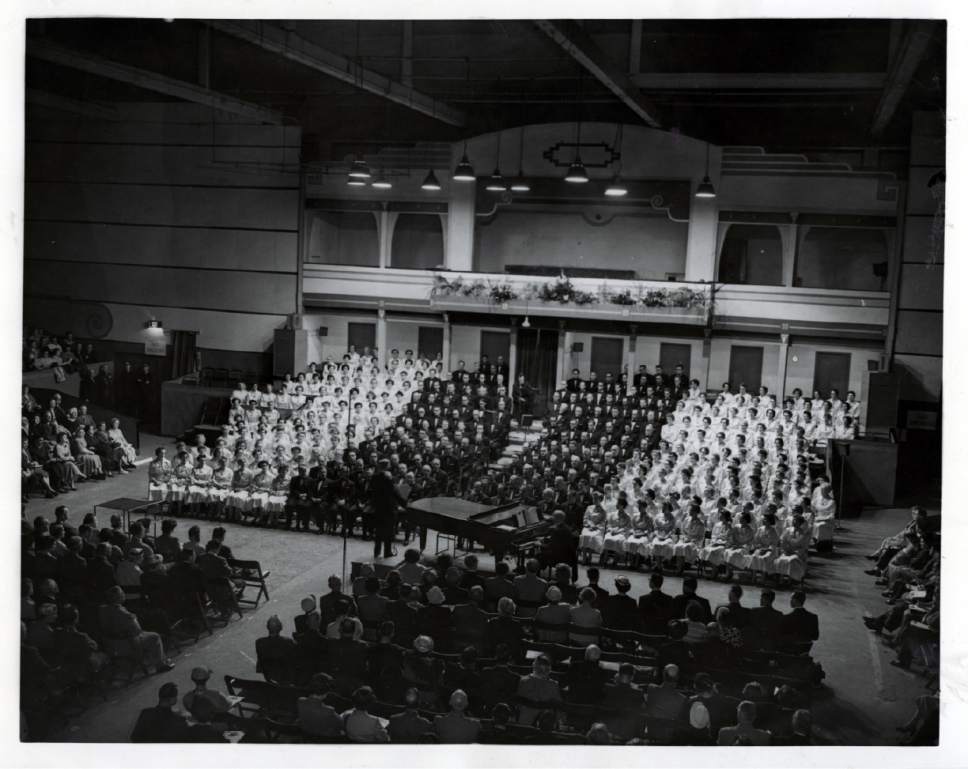

The squabble over whether to sing at Donald Trump's inauguration next week may be unlike any other controversy for the famed Mormon Tabernacle Choir.

But it is hardly the only time "America's choir" — as Ronald Reagan dubbed the singers — has been touched by politics, says Michael Hicks, a Brigham Young University music professor who wrote a "biography" of the choral group.

During World War II, for example, then-conductor Spencer Cornwall independently made arrangements with the Army to have the choir sing background music in a documentary film produced by the U.S. War Deparment, Hicks writes in his 2015 book, even though not all LDS leaders — including at least one member of the faith's governing First Presidency — believed the country should be fighting.

The 1945 movie was "The Battle of San Pietro," which documented the U.S. victory in Italy. When J. Reuben Clark, then a counselor in the First Presidency, got wind of the choir's involvement, he was furious, Hicks writes in "The Mormon Tabernacle Choir: A Biography."

Clark talked with the other counselor in the presidency, David O. McKay, and they agreed that it was "improper" for the choir to be used in that way — performing in a film glorifying the war effort "while our boys are being blown to pieces."

Cornwall was instructed to keep the choir out of any more war films.

The problem was the troupe's reputation, Hicks writes. "Clark and McKay believed that the choir needed to trade on its own broadcasts' pervasive theme of "peace this day and always.'"

In the end, he says, it was The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' "reputation at stake, not the choir's."

Despite "lingering hostility" from Mormon prophet Heber J. Grant toward President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal policies, the choir put together a tribute broadcast to Roosevelt the day after his April 12, 1945, death.

The group's best-selling and Grammy-winning 1959 recording of "Battle Hymn of the Republic," Hicks writes in an email, "essentially crowned the choir's Americanist reputation."

No musical troupe "could be more politically mainstream," he says. "But an album of international songs in 1963 raised issues about political endorsements, specifically of the Soviets and Zionists."

The album "This Is My Country" carried the subtitle "The World's Great Songs of Patriotism." It included music from several regions. The last piece was an Israeli song, "Hatikva," which LDS leaders worried "might imply support for Zionist causes," Hicks writes.

If that tune made the cut, Mormon authorities said, producers should add "music from Arab sources."

But McKay, by then church president and "rigorously anti-communist," nixed one selection, the scholar writes, "the Russian song "Meadowland," with lyrics from the perspective of "a Red Army recruit who vows to defend his homeland."

The choir's 1965 album, "This Land Is Your Land," rankled LDS apostle Ezra Taft Benson, who complained that the title song was written by Woody Guthrie and further popularized by Pete Seeger, whom he described as "two hard-core Communists."

"It's safe to say that, under a President Ezra Taft Benson, the choir would never have been authorized to sing 'This Land Is Your Land,' " Hicks says in the email, "even at a presidential inauguration."

The choir's first performance at a presidential inauguration was for Lyndon Johnson in 1965, he says, "which followed a planned CBS tribute to the fallen John F. Kennedy (which was canceled because of the killing of Lee Harvey Oswald that day)."

McKay called that inauguration invitation "the greatest single honor that has come to the Tabernacle Choir."

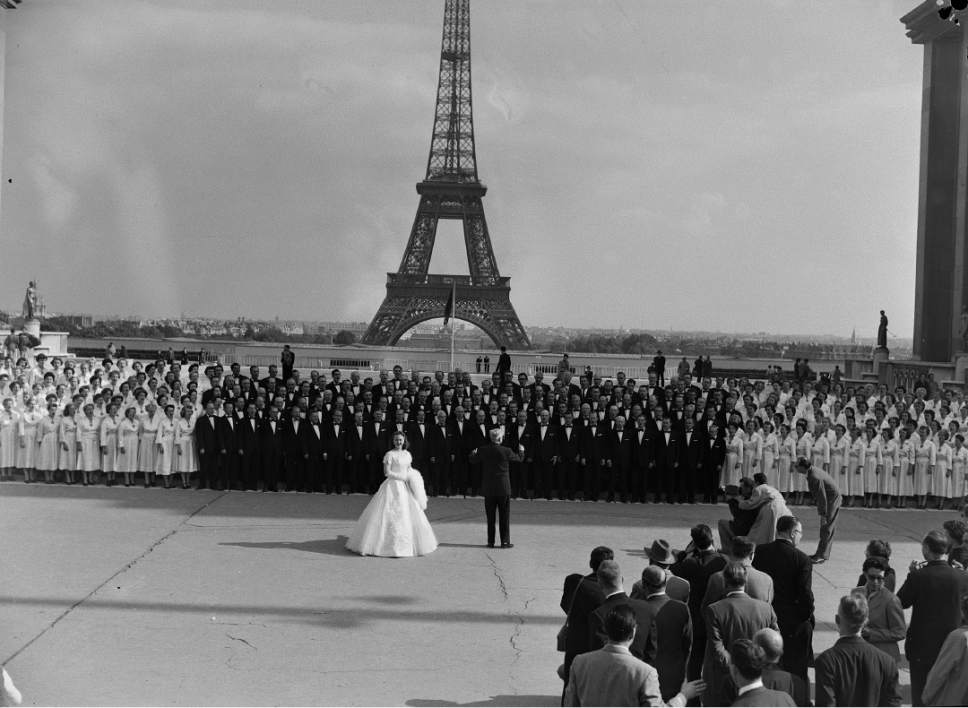

Thereafter, these Mormon singers were invited to several presidential inaugurations, Hicks writes. "They were happy to be welcomed into the official state fold, since the whole mission of the choir beginning with Evan Stephens in 1890 — yes, timed with the Manifesto [announcing the faith's formal end to plural marriage] — was to bolster the church's image in the eyes of a nation that had demonized them for polygamy and for quitting the country in the first place to settle outside its boundaries and set up a quasi-kingdom."

Before the Trump flak, though, the most common choir controversies were between LDS leaders and the conductors, arguing about apparel, scheduling, repertoire and potential commercialism.

Or how far to push Mormonism on its weekly CBS broadcast, "Music and the Spoken Word," the longest-running uninterrupted network broadcast ever.

The "spoken word" part originated with Richard L. Evans — later in the faith's Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Evans was "a radio orator on the level of the best political spokesman," Hicks says. "He was indeed a nonpolitical statesman in the ears of millions of listeners."

The only controversies connected with Evans were "when he quoted unsourced 'scripture' that was presumably biblical but was actually Mormon scripture," the historian writes, "violating the nonsectarian expectations of free public service broadcasting."

When listeners wrote to him for the references to a "scriptural" quote he gave — and thousands did, year after year," the historian says, Evans had "a team of helpers who would package copies of the Book of Mormon or the Doctrine and Covenants to accompany his letters of response."

Even so, Evans' "oratory on the public stage of Mormonism has never been matched," Hicks concludes, "nor has his influence."

Twitter: @religiongal