This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

About three-fourths of the world's citizens live in a country where they can't freely exercise their religion and many do so in the face of great risk, possibly even death, a top State Department official said Friday.

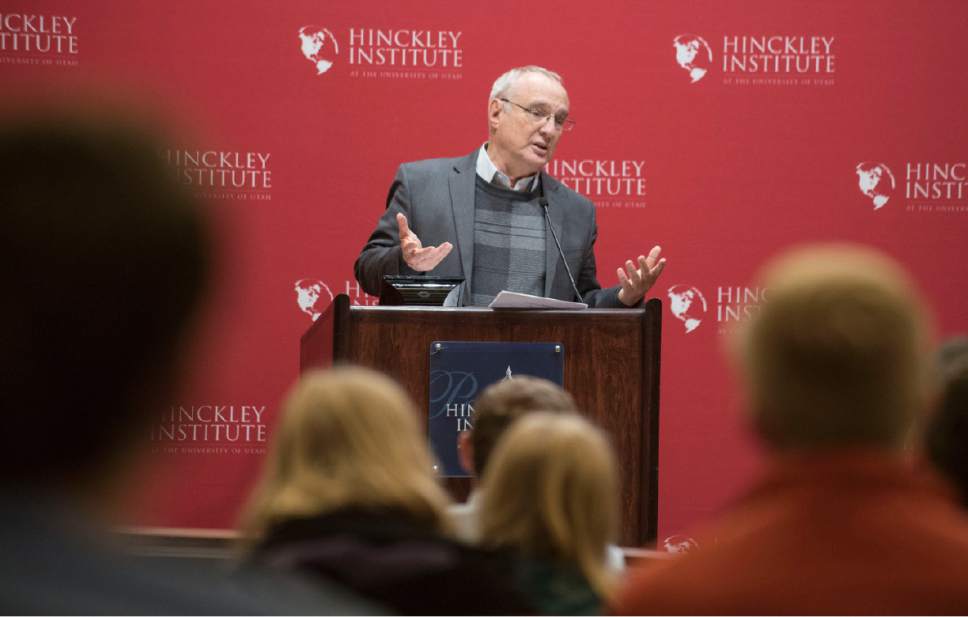

But David Saperstein, the State Department's ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom, told an audience at the University of Utah that the United States has worked to defend the rights of religious minorities and expand religious liberty around the globe.

"I'm extremely proud of the work the U.S. government has done on this," he said. "I'm truly honored to have been able to play a role in it and I cannot tell you how inspired I am when I … see people's commitment to live out their religious lives, sometimes at enormous risk, but to do so with fervor, with love, with commitment to community that leaves one with a sense of joy in even the worst situations."

Threats to religious freedom can come from oppressive laws enforced by the government, he said, or repression by other, sometimes violent, groups, perhaps most prominently the terror carried out by the Islamic State.

"What can we do in the midst of all the violence and fighting and the military action?" he asked. "How can we set in motion those conditions that will allow these minorities [to return home] when ISIL is pushed out?"

It starts with sustaining families in refugee camps where they can get education for their children and health care for their families. It requires local police and defense forces that won't run in the face of the enemy. There has to be accountability for perpetrators of violence and terror. And there has to be some way to untangle conflicts that arise when people return to their homes or businesses, only to find others have moved in.

While ISIL and other Islamic extremists garner most of the attention, Saperstein said, there are extremists from every major religion that oppress minorities in parts of the world.

A quarter of the countries in the world have laws that make blasphemy a crime. While most do not enforce the laws, in a dozen countries, blasphemy is punishable by death. Saperstein said it makes it hard to persuade countries to abandon those laws when several countries in Europe and even six U.S. states — Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wyoming, Oklahoma and South Carolina — have blasphemy laws on the books.

"No one should have to go to jail for simply stating what their heartfelt belief is, but that is the reality that many people face," he said.

Saperstein spoke of how, in March 2015, a woman in Afghanistan stopped for prayers on her way home from work and got into a dispute with the caretaker of the shrine. He accused her of burning a Quran, and a mob gathered. Police tried to intervene but soon retreated, and the woman was beaten with sticks and boards, run over with a car, stoned and set on fire as people recorded the incident on their cellphones.

"These are serious, serious infringements on religious freedom that have a chilling impact every day on the lives of minority communities," he said.

Recently, Russia enacted rules that "deregistered" some religions that led to increased harassment of others, including Mormons.

Saperstein said the State Department does what it can to encourage governments to be tolerant of diverse religious views, even when progress may be incremental. He pointed to Vietnam, where the National Assembly voted Friday on new laws regarding religious freedom, as an example of where slow progress can be made.

At the same time, he acknowledged that human rights and religious liberty are just one component of U.S. global strategy.

"Our foreign policy reflects many different interests, amongst those are a human-rights interest," he said. "There are military interests, there are economic interests, there are broad strategic interests that we have in different countries."

A nation like Saudi Arabia, for example, is important to U.S. interests in the Middle East but is also repressive to minority religions, and its treatment of religious minorities has been a concern to the U.S. government.

Twitter: @RobertGehrke