This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Editor's Note • This is the first in a periodic installment hoping to highlight average people doing under-appreciated work in our communities. If you know of someone who should be featured, contact the author at the email address above.

There were nights when Michael Cumming sat enveloped in the darkness, a bottle of whiskey in one hand, a revolver in the other, waiting, he says "to get to the point where I could just cross over."

He had spent a dozen years in the military, and seen brutal warfare during his first short deployment in Fallujah, Iraq, in 2004, in the offensive surge in Balad in 2006 and trying to maintain order in Mosul in 2009.

Cumming left the Army in 2012 and moved to Utah to get a degree in parks, recreation and tourism, but while he had escaped death overseas, now, without the support of his fellow soldiers, it haunts him at home.

"Adjusting to not being in the military anymore, that was the first time I really started reflecting on things that had happened overseas. I started thinking about watching some of my buddies get killed and some of the stuff I did, too. It's just — life slowed down, I guess," he told me recently.

Studies say between 1 in 5 and nearly 1 in 3 Iraq and Afghanistan veterans suffer from PTSD, and roughly half never seek treatment. One recent study said 20 veterans a day die by suicide.

Fortunately, two fellow veterans saw Cumming's struggles and connected him with a Veterans Administration counselor who offered another way out: Climb.

Cumming had been an avid mountain climber in his home in Washington before he joined the Marine Corps out of high school in 2000. When his time was up, the Marines told him it would take six months to get back into the corps, so he went next door to the Army recruiter and was in Fort Hood, Texas two weeks later.

Now, his counselor suggested getting back on the mountain and back into the outdoors could help him clear his head.

"It helped me kind of get grounded again, to be able to have somewhere to release everything and then come back and be able to function better as a citizen, in a more healthy way," Cumming said.

But he didn't stop climbing.

"Once I understood that had helped me and worked for me, I thought, 'Maybe this would work for other vets,' " said Cumming, who has a dagger tattoo on his right forearm and the letters "U.S.M.C." from his time in the Marines on his right bicep.

Cumming did a small internship with the VA's therapeutic recreation program and saw the potential to help many more. On a later internship with Mountain Education and Development, he launched his own program and it took off.

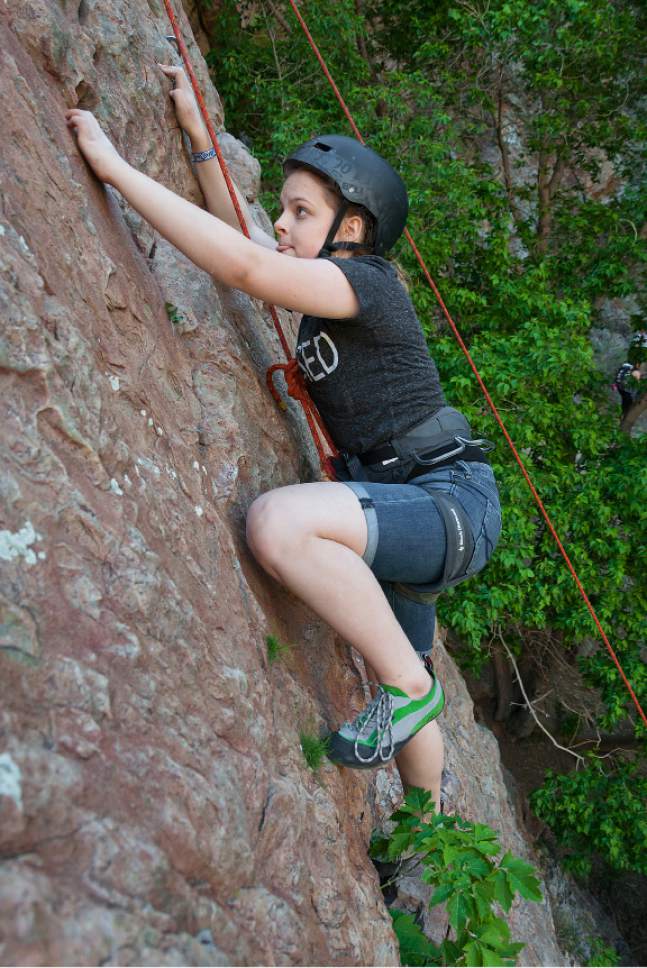

A year later, Operation Climb On spun off its parent organization. The program is designed to take returning veterans, whether they are experienced climbers or not, and put them in the outdoors or the side of a mountain and, as importantly, to create a network of support for those who might have otherwise fallen through the cracks.

Since 2013, Cumming estimates that as many as 100 veterans have participated in the program, with many of the earliest participants staying on as instructors.

"I think one of the big things it does is the camaraderie they miss after leaving active duty," he said. "Another big one is, unlike a lot of other sports or activities, climbing requires a level of trust between you and someone else."

Steve Sorrels was one of a half-dozen vets who spent Saturday evening cooking hamburgers and hot dogs and climbing Storm Mountain in Big Cottonwood Canyon

"It gets vets together, it gets them out of their homes, gets them out with other vets who may be going through some of the same issues they are," he said. "[The vets] get to network and [so do] the military kids, and they all kind of deal with the same thing."

Liberty Mountain, a South Jordan outfitter, has donated some climbing gear to Operation Climb On, and Black Diamond has given the group a discount on purchases, but most of the money for the equipment and food had come straight out of the wallets of Cumming and other instructors in the program.

This year, the Wounded Warrior Project is paying for events and helping connect Operation Climb On with other veterans whom Cumming said they wouldn't have connected with otherwise.

Cumming would like to see the idea of Operation Climb On, if not the organization itself, expand nationwide.

"I've had a couple other vets contact me over the last couple years who are interested in running a similar program," he said. "You can climb anywhere in any state, so I think it would be cool to see … other groups doing climbing for vets across the U.S. We can only do a small portion."

Twitter: @RobertGehrke