This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

It would happen two or three times a week.

As I would settle into my desk at work, the phone would ring and the caller-identification number would alert me that I needed to clear my calendar for at least 20 minutes.

Hopefully, I already would have gotten my cup of coffee.

"How's my friend?" the gentleman would say in a soft, somewhat halting voice.

He would go on to tell me about his day, his efforts to preserve the bit of his family's history that became his cause and what he planned to do the rest of the day to make people smile.

Those calls regularly persisted for more than 20 years.

The gentleman was Marion Cox, a retired carpenter, who was in his late 70s when he decided I was his friend, although we had never met.

He died Monday at age 96, and while his voice had become as familiar to me as any family member, I still never met the man face to face.

Cox made himself my friend after I wrote a story in the mid-1990s about a massive expansion planned at The Family Center at Fort Union, which the then-Salt Lake County Commission was poised to make possible through a zoning change.

That forced him to take action, he told me in the first of hundreds of calls I would field from him through the years.

He was determined to save his ancestors' home, which was built in 1849 and stood in the way of the development. It was scheduled for demolition, but Cox would have none of it.

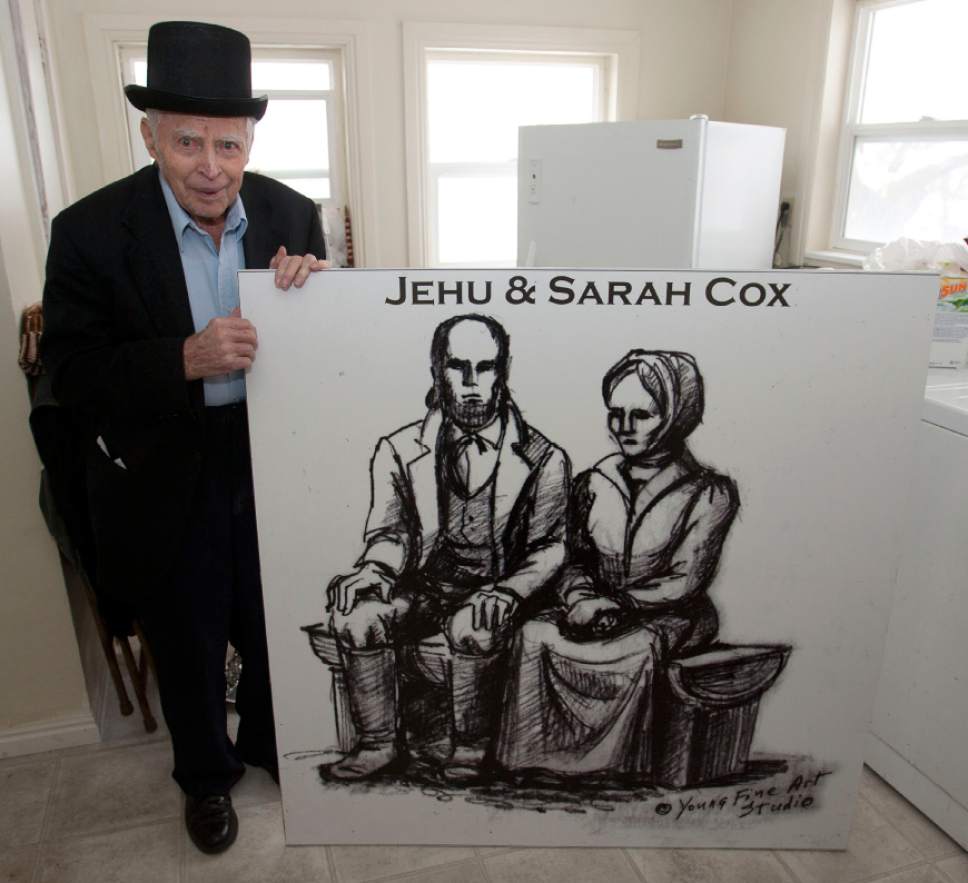

He became a regular at commission meetings, usually adorned in a long, black jacket and a stovepipe hat, pleading strenuously for the home's preservation.

The original owners of that abode were Jehu and Sarah Cox, Marion Cox's great-grandparents, among the earliest Mormon pioneers.

They came to the Salt Lake Valley shortly after the arrival of Brigham Young and built the house a year later. At Young's request, they donated 10 acres around the home so a fort could be built to protect farmers.

Their role in pioneer history was a source of pride for Cox, a seemingly simple man who made a decent life for his family as a carpenter and builder.

Saving that house became his mission.

Finally, through his persistence, the developers came up with a plan: They would tear down the home brick by brick and then reconstruct it elsewhere within the Fort Union complex. It didn't quite turn out that way. Crews instead put up a replica of the original home in the new location. A plaque now denotes the house's place in Utah history.

After that victory, Cox wasn't through. He prodded county and Midvale officials to erect a bronze statue of his great-grandparents to stand in front of the home.

County officials eventually told him that if he could raise $80,000 for construction of the statue, they would have it placed on the site amid the brick-and-mortar retailers that dominate the surroundings.

Daughter Alease Guymon told me this week, he could muster only $14,000. "He's still got $66,000 to go," she said.

While some officials grew irritated at Cox's constant coaxing, he nonetheless became a beloved figure at the County Government Center and Midvale City Hall.

Wherever he went, he passed out yellow "smile" cards. I would get some of those cards in the mail from time to time.

His daughter also told me that whenever he met new people, his first question was what high school they attended. He then would ask them to sing that school's song. Cox had gone to Tooele High School and, according to Alease, he never could remember his school's song.

A few years ago, Midvale officials had a ceremony in which they made Cox the honorary mayor of Fort Union. In 2014, he rode in the Midvale parade as mayor of Fort Union, sitting atop his son's crane.

While enjoying that moment of stardom, a hit-and-run driver smashed into his gold Camaro, which he had parked nearby, causing $1,400 in damage. Cox told me later it took a whole box of smile cards to get over that.

He never held public office. He wasn't political, but he showed what any regular person can accomplish if dogged enough to do it.

His life was his family. His wife, Mary, died six years ago after the two had been married for nearly 70 years. He leaves five children, 20 grandchildren and 37 great-grandchildren.

All of them have an abundant collection of smile cards.