This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Witness after state witness testified Tuesday about the odd relationship between a former Utah attorney general and a pair of businessmen that included paid trips to a luxury California resort and a plea agreement to criminal charges negotiated in secret.

But that former attorney general was not John Swallow.

The central figure of the day's testimony was Mark Shurtleff, but he is not on trial. And the man who is — Swallow, his successor — seemed to be little more than a bit player in the narrative of corruption and greed Salt Lake County prosecutors want 3rd District Court jurors to hear.

Swallow was an equal partner, prosecutors contend, in a triangular criminal enterprise that comprised him, Shurtleff and the late "fixer" Tim Lawson — a trio who solicited money and favors from Utah business executives in exchange for legal cover or protection from the attorney general's office.

A prime target of that scheme, prosecutors say, was Marc Sessions Jenson, who has testified to being coerced by Shurtleff into paying Lawson about a quarter of a million dollars for help in resolving a 2005 criminal case.

Jenson's longtime friend and employee Paul Nelson testified Tuesday to witnessing the alleged extortion scheme, but he couldn't say that Swallow played a role.

"Did you think John Swallow was a part of the scam?" defense attorney Scott C. Williams asked Nelson under cross-examination.

"I don't think so," Nelson replied.

Similarly, Williams pressed Jenson's personal assistant, Peter Torres, on whether he had cut checks for Swallow the way he had for Lawson each month between 2007 and 2010, and whether Swallow was someone who might persuade Shurtleff to drop Jenson's criminal case.

"John Swallow was not a conduit for us," Torres said, adding that no money was paid to Swallow from Jenson's accounts.

Torres, who worked for Jenson from 2000 to 2010, also testified that he never saw or was told by others that Swallow tried to shake down Jenson for money. The former Republican attorney general was also never paid for any legal services, Torres said, though Swallow turned up at Jenson's office, looking for work when he was a lawyer in private practice.

Swallow, 54, pleaded not guilty to 13 felony and misdemeanor charges, including counts of racketeering, bribery, accepting prohibited gifts, making false statements or records, obstructing justice, and tampering with evidence.

If convicted by the jury, Swallow could face up to 30 years in prison.

The charges grew out of a multiyear investigation into allegations of a pay-to-play climate inside the Utah attorney general's office before and after Swallow was in office.

Shurtleff was originally charged as Swallow's co-defendant in 2014, but the cases were separated and Shurtleff's case was dismissed in 2016. Lawson was charged in a separate case, but he died in August.

Prosecutors fought for — and won — the permission to use witness testimony about Shurtleff and Lawson in the trial, and they say it supports the second-degree felony racketeering charge Swallow faces.

Nelson and Torres said Tuesday that they knew in 2009 that Swallow would be the next attorney general. It was "common knowledge," Nelson said, and something that Swallow told people.

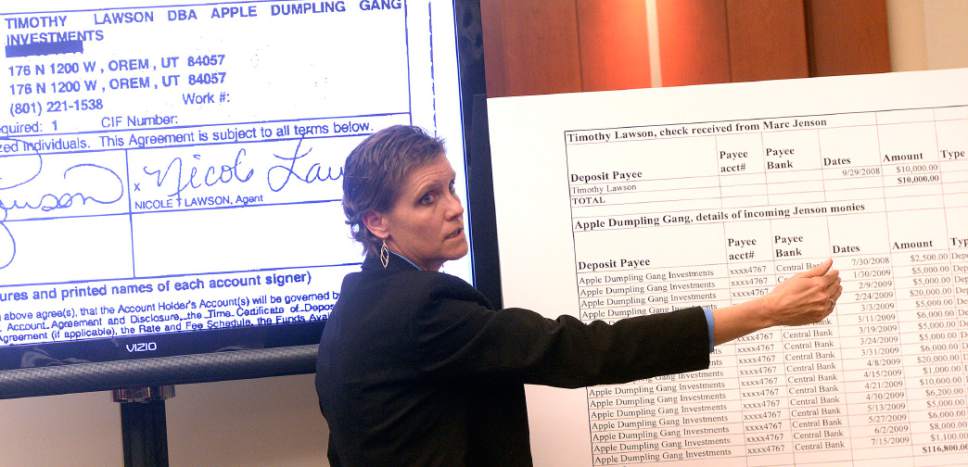

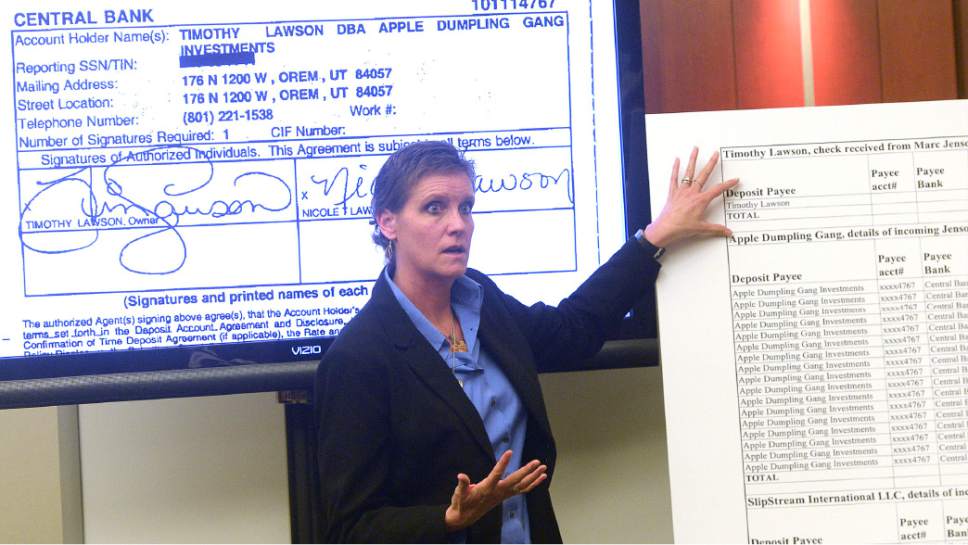

Wire transfers from Jenson to Lawson also were the subject of testimony from an FBI forensic accountant who combed through the financial records gathered in the case.

Heidi Ransdell said she found 18 payments made by Jenson to Lawson — most in wire transfers — that totaled more than $134,000.

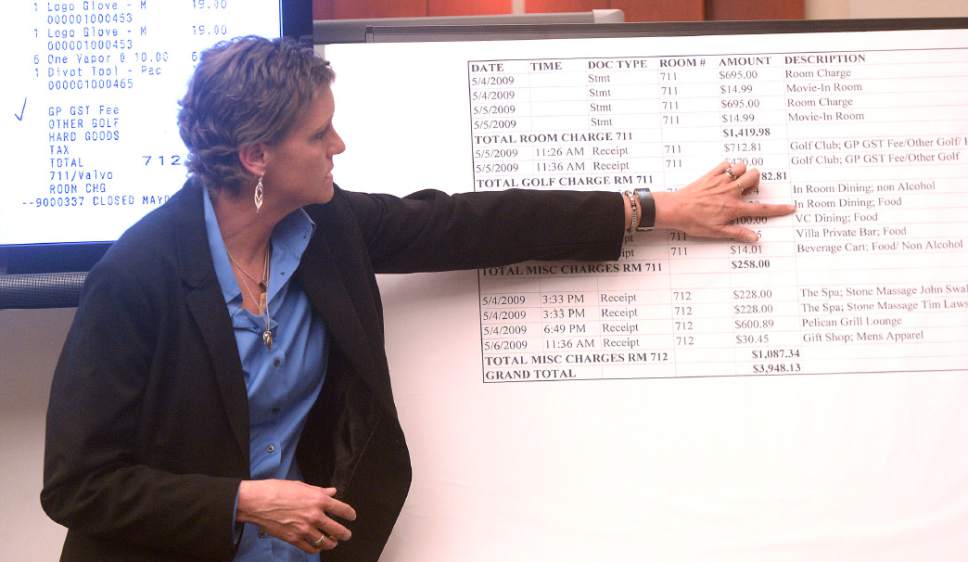

Ransdell said she also reviewed receipts for the villa at Pelican Hill, where Shurtleff and Swallow stayed in May and June 2009. The documents show that Jenson paid for their lodging, meals, golf and other amenities, Ransdell said, each trip costing about $6,000.

Under cross-examination by Swallow's attorney Cara Tangaro, however, Ransdell acknowledged that most of the receipts provide no specific details, so there's no way to know whether it was Swallow who ordered an expensive steak, a bowl of pasta or a glass of vodka on Jenson's dime.

Ransdell agreed when Tangaro noted that the only receipts that can be specifically linked to Swallow were those he signed for on a third trip with his wife, Suzanne, in July 2009.

Tangaro also asked Ransdell whether she had looked at Swallow's credit card bills to see that he and his wife had paid for their plane tickets, rental car and groceries during that third trip.

"I didn't see those," Ransdell said.

A fourth witness on Tuesday, Darl McBride, also testified about a strange encounter with Shurtleff, from whom he sought help in resolving a business deal that went bad with Mark Robbins, a former Jenson associate.

McBride told the jury about a 2009 meeting with Shurtleff at Mimi's Cafe in Sandy, where Shurtleff asked him to take down a "digital bounty" website, Skyline Cowboy, he was using to try to locate Robbins.

McBride, who secretly recorded their conversation and turned over a copy to investigators, said Shurtleff told him the site was making it hard for Robbins to close business deals and raise the money to pay his debts. Shurtleff also said he would try to get Jenson to pay McBride the $2 million Robbins owed.

The proposal was odd, McBride said, because he expected that the three-term attorney general would be on his side, not defending Robbins.

And not once in the conversation did Shurtleff mention Swallow, McBride said.