This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

New LDS Church data show a growing divide in the religious makeup of Utah's two most populous counties, a demographic shift that has sweeping political and cultural ramifications.

The 3 million-strong Beehive State, as a whole, remains roughly 62.8 percent Mormon.

But Salt Lake County, home to the headquarters of the The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, continues to see its portion of residents on LDS membership rolls decline. As of Sept. 30, it stood at 50.07 percent. In neighboring Utah County, which includes the faith's flagship school, Brigham Young University, Mormons make up 84.7 percent of the population, an increasing share from recent years.

The LDS Church provided eight years of county-by-county membership numbers to The Salt Lake Tribune, and the data back what independent Mormon demographer Matt Martinich has noticed by tracking where new congregations are created.

"Salt Lake County ... has become increasingly more cosmopolitan, housing has become more expensive, and the church has overall really struggled in urban areas," said Martinich, who lives in Colorado. Whereas, Utah County has bigger homes that often are cheaper, attracting younger Mormon families who also may want to live near others from the same religion.

For Mormons deciding where to live, Martinich suggests that Salt Lake County "is just culturally less attractive, economically less attractive, socially less attractive."

—

Capital of Mormonism isn't so Mormon • Salt Lake County Mayor Ben McAdams has watched as his Sugar House neighborhood and other parts of Salt Lake City have become less Mormon over time.

"There is certainly some self-selection. It is human nature to want to live around people who accept you and who are like you," McAdams said. "But I want to defend Salt Lake County. As a practicing Mormon, I think it is a great place to raise kids. I think I'm raising kids who are going to be stronger in their beliefs because they will do it out of choice and not out of peer pressure."

The share of Mormons in Salt Lake City — though not delineated in the church's data — is clearly lower than in the county as a whole, says McAdams, who gave his own estimate.

"In Salt Lake City, where I am, we are well below 20 percent, and I think that is good for me and my kids. We have to bond with our neighbors not based purely on religion. … I guess you used to be able to presume that people you interact with are LDS and now you can't make that presumption, and that is OK."

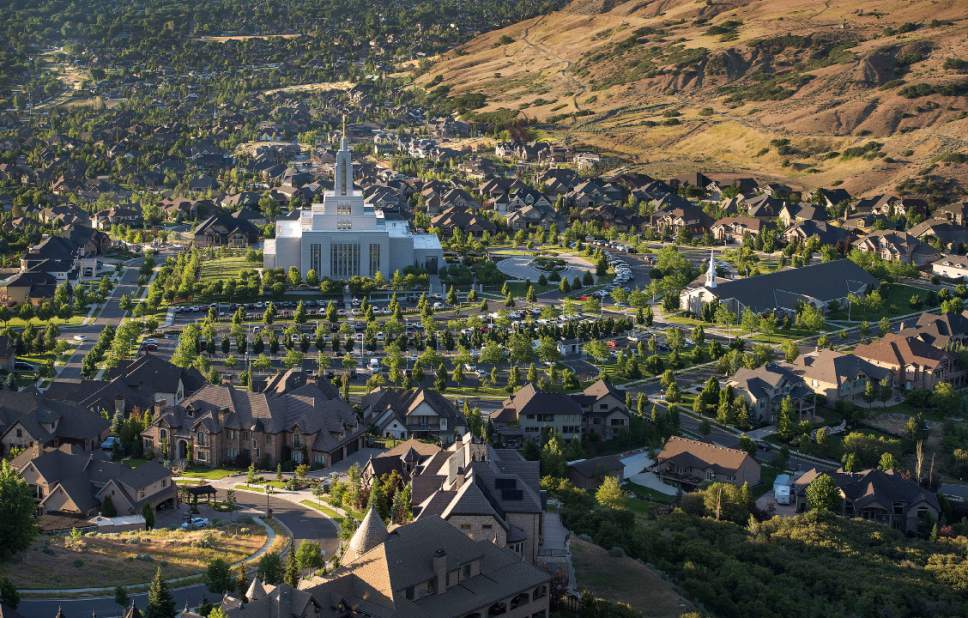

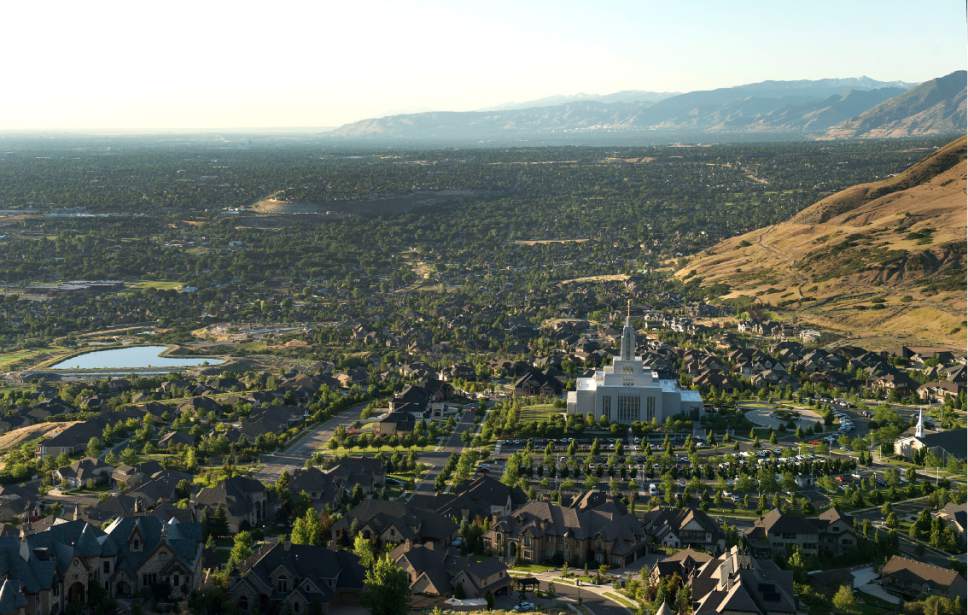

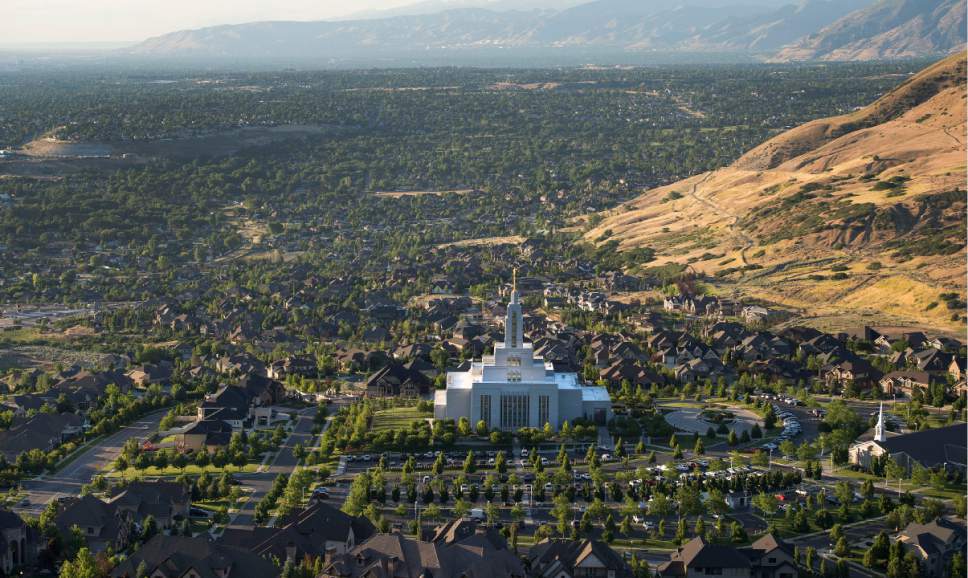

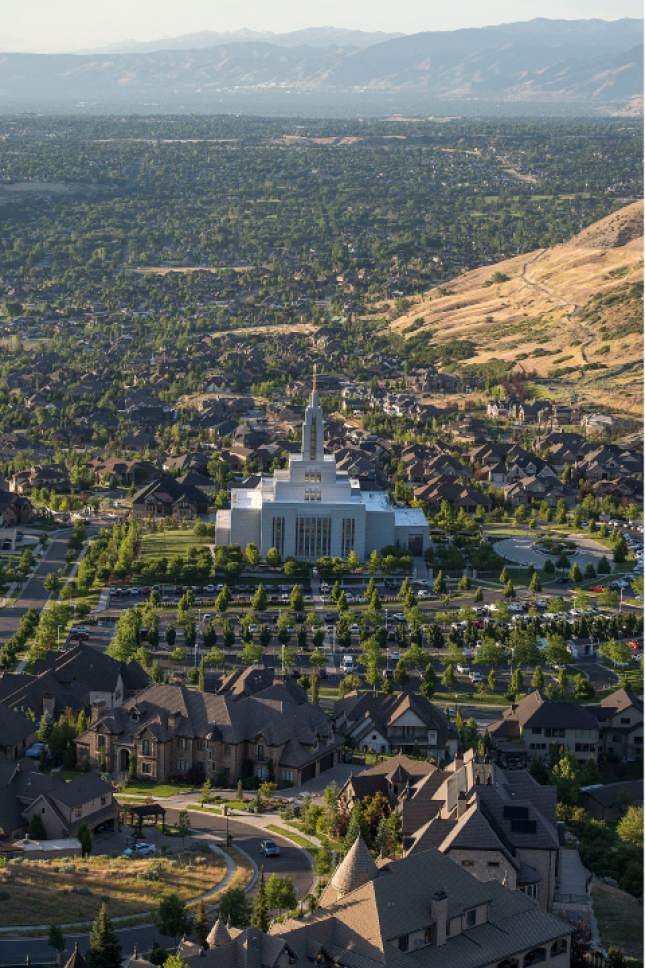

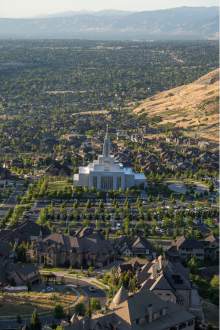

Mormons in Salt Lake County appear more likely to live in the southern cities, close to Utah County, as indicated by the church having built one temple in Draper and two in South Jordan.

Jim Miller grew up in Lehi and moved to nearby Saratoga Springs 12 years ago. He's now the mayor of that booming Utah County city. He never has noticed any significant shift in the Mormon population of his neighborhoods. Just about everyone is a member. He believes people are attracted to the area more for the lifestyle than to live next to people of the same faith, since this city on the west side of Utah Lake has modern homes within a close drive of fishing, boating and ATV trails.

In April, LDS Church President Thomas S. Monson announced that five new temples will be built throughout the world, including one in Saratoga Springs. When completed, it will be Utah's 18th temple and the fifth based in Utah County. Salt Lake County has four.

"It was a pretty cool feeling to be there when the announcement happened," Miller said.

—

Ups and downs of LDS data • Since at least 1940, the LDS Church has provided membership data to the state, which uses those statistics along with IRS figures, school enrollment, health information and building permits to build population estimates.

That responsibility shifted to the University of Utah's Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute in 2016, and the LDS Church struck a deal with the U. that for the first time would have kept the data private.

The U. denied Tribune records requests and declined to talk about the data, citing an active confidentiality agreement. But when asked, the LDS Church gave The Tribune what a spokesman said was the exact set of numbers it gave to the U. That spokesman did not explain why the church has a confidentiality deal with the school.

But it is because of that deal that Pam Perlich, chief demographer at the Gardner Institute, said she couldn't talk about what she refers to as "the LDS method," saying only: "It is a valuable data set to help us understand our unique population."

In the past, Perlich has noted the shrinking share of Utahns who are Mormon is largely a result of economics. People move to the state for jobs, and those newcomers don't tend to be as Mormon as the residents already living in the state.

When combined with census estimates, the new data show that Utah was 62.8 percent Mormon in 2016, the same percentage it was in 2009. But during those years, Salt Lake County dipped from 51.5 percent LDS in 2009 to 50.07 percent last year. If the trend holds, Salt Lake County soon may join the ranks of Utah's minority Mormon counties. That group includes Carbon (49.9 percent), San Juan (35.5 percent), Summit (29.4 percent) and Grand (26.5 percent).

Salt Lake County has a population of 1.12 million people, and 561,433 were on the LDS rolls in 2016. In most years, the county added at least a few thousand Mormons as it continues to grow, but not in 2016. The county saw a total population spurt of 16,732 people but a decrease of 318 in the actual number of Mormons.

One possible reason for the drop is the controversy over the church's November 2015 policy identifying same-sex LDS couples as "apostates" and restricting their children from baptisms and baby blessings until they turn 18. Hundreds of Mormons, most of them inactive, attended protests where they resigned their memberships. Martinich said that may have played a role in those numbers, but he expects that to be a one-year blip, while the larger demographic shift should persist in the years to come.

In contrast, Utah County rose from 83.6 percent LDS in 2009 to 84.7 percent in 2016. It has a total population of 592,299, slightly more than half Salt Lake County's size, of which 501,725 are Mormons. At this pace, it is possible that Utah County, though much smaller overall, would have more Mormons numerically than Salt Lake County within the next 10 years.

The figures don't include "in transit Mormons," members the church no longer can identify by address.

—

On the rolls vs. in the pews • Martinich notes there's a big difference between being on the rolls and being a participating Mormon. He estimates that 40 percent of U.S. Mormons are active, and he has slightly different estimates for Salt Lake County. His best guess is that roughly half Salt Lake County's members are churchgoers, which would be 25 percent of the county's population. He says Utah County's activity rate is higher, so maybe 60 percent of its residents regularly attend worship services.

"More areas of Utah County still maintain characteristics of more rural counties. That attracts a more traditional family dynamic," said Robert Spendlove, a senior economist at Zions Bank. "In Utah, a more traditional family dynamic would be Mormon and Republican."

Spendlove is a GOP member of the Legislature living in Sandy. Salt Lake County is the state's only real political battleground, where the stronger Republican areas often are places with bigger Mormon populations, namely the cities in the south end of the county, which boasts three of the county's four LDS temples. The Democratic strongholds, on the other hand, are in areas like Salt Lake City, which hasn't elected a Republican mayor in four decades and where Mormons are vastly outnumbered.

The LDS Church is well aware of the population shifts in the state, though leaders attribute it more to family decisions than people wanting to live around those of similar religious or political beliefs.

"Many people with families (including church members) have moved to areas where the cost of living may be more affordable or to be closer to new employment centers or schools," LDS Church spokesman Eric Hawkins said recently. "Obviously, this impacts the number of church members in both areas. So you'll see a decrease in [Mormon congregations] in one area and an increase in another."

Still, this growing political and religious divide comes at a time when economic prosperity is driving new businesses to relocate and homes to be constructed along the line between Salt Lake and Utah counties.

"Salt Lake County and Utah County are so different but are becoming one big metro area," said Morgan Lyon Cotti, a political scientist at the U. Part of the religious divide is driven by housing costs, but she suggests some of it also might come from workers more willing to commute, especially those who have relocated from more crowded states like California.

That's what Carlton Christensen, Salt Lake County's director of regional development, has noticed, and he expects the divide to remain.

"Folks are living where they feel the most comfortable living," he said, "and subsequently commuting to work."

Possibly underscoring that trend, McAdams and Saratoga Springs' Miller say they make no assumptions about the religious affiliation of the people they interact with in the workplace, because doing so is far more fraught than it might have been in years past.