This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Drug-related offenses and overdose deaths shot up last year in Salt Lake City, and several other types of misdemeanor crime also climbed.

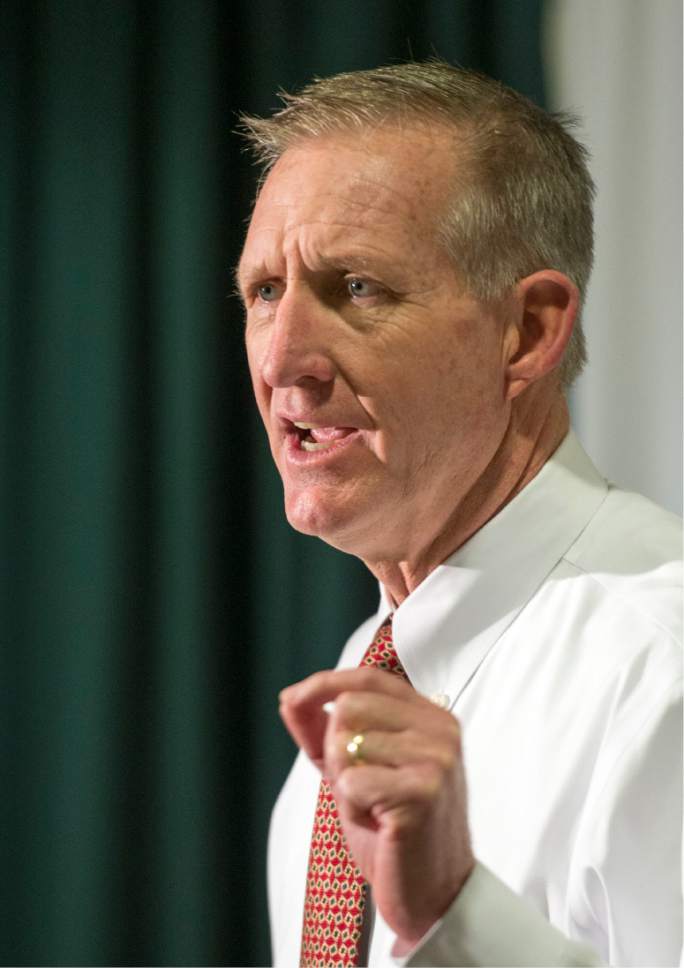

The reason, Police Chief Mike Brown said this week, is a policy implemented in early 2016 by Salt Lake County Sheriff Jim Winder that restricts which offenders can be sent to the county jail. Without jail time as a deterrent, police officers are left "without any means of authoritative presence, which, in turn breeds, disorder," according to a police department staff report.

Winder pushed back on Brown's assertions in a Thursday interview, saying it was far too early to make a correlation between the jail policy and rising crime. The two law enforcement leaders have not been on talking terms in recent months, as the homeless shelter controversy has heated up.

"It's just that we can't stop the bad behavior, sometimes, that is occurring down there [in the Rio Grande area]," Brown told the Salt Lake City Council at a Tuesday work session. "The jail restrictions are causing the officers of the Salt Lake City Police Department some problems."

Brown said from 2015 to 2016, drug cases handled by police were up 34 percent, and the number of alcohol and drug-related deaths rose by about 50 percent, to 29. The amount of drugs seized — measured in street-level doses — climbed 82 percent. Several other misdemeanor offenses also rose, even as Part 1 felony offenses (which include homicide, rape, aggravated assault and burglary) dropped last year by 7 percent in the city.

Brown said the reason for the increase is the county's restrictions on which offenders can be booked into jail after an arrest.

Implemented in March 2016 by Winder, the restrictions prioritize jail space for people suspected of felonies, sending those suspected of misdemeanors elsewhere — such as detoxification centers — or letting them go with a citation. Offenses that fall under the jail-space restrictions include drug violations, private property damage, retail theft, simple assault and trespassing, among others. The new policy was intended to help reduce overcrowding at the frequently packed jail, and help reduce recidivism by instead placing people in drug treatment and other supervised release programs.

But according to Brown, it also has meant more misdemeanor offenses, because people know they won't be sent to jail.

In 2016, total Salt Lake City arrests resulting in a trip to the jail dipped to a four-year low of 7,368, down 25 percent from 9,772 in 2015, according to the department report.

Total arrests in the city generally trended upwards month-to-month in 2015, the report said, consistent with previous years as the population of Salt Lake City grew. But the arrest trend gradually reversed in 2016 "once the jail restrictions were put into place," the report said.

According to Brown and the department report, officers are now often issuing citations, rather than taking people to the jail.

But "even when multiple citations pile up in the court system for repeat offenders, these offenders also know they run no risk of being booked when those citations turn to warrants either." So they continue to offend, Brown said.

The data "demonstrates the need to be able to use incarceration as a means for prevention when no other options are available in the community or welcomed by substance abusers," according to the report. Without the possibility of jail, Brown told the council, "we can't interrupt bad behavior."

Several council members stressed the need for more state and federal funding to expand regional drug treatment resources, as part of the equation to reduce drug crimes and overdoses. Brown also mentioned the department's plans to hire two or three more in-house social workers, as part of a new department program meant to help the homeless population and drug users.

A frustrated Winder took issue with Brown's statements, saying it was convenient for the chief to blame the "big bad sheriff's policy" for the rise in crime.

"I think it's way too early, and frankly impossible, to tell if a single policy about misdemeanor booking restrictions can so affect crime rates," Winder said.

Crime rates often fluctuate year to year, he said, for various reasons. In addition, Winder said it was inappropriate to correlate a one-year crime increase to a single county jail policy without factoring in countywide or statewide crime trends for 2016 — which have not yet been released.

Due to jail overcrowding, suspects who were booked into jail for a misdemeanors prior to the jail restriction policy's implementation often didn't stay there long, anyway, Winder said. He said he is skeptical that taking a "ride down to the jail" — then being released hours later — helps reduce a person's tendency to commit another crime.

"It is impossible for me, and I dare say for [Brown], to comment on the specific genesis of the increases," Winder said, later adding that he's not sure where Brown "gained his statistical approach, but it's not one that's known to me."

Twitter: @lramseth