This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

With tears in his eyes, John Swallow stood Wednesday afternoon before the jury — eight men and women who will decide whether the former Utah attorney general is guilty of crimes worthy of prison or leaves the courthouse a free man.

His lawyer had Swallow, who did not testify in his own defense, rise because "he needed the opportunity to stand up and be seen by them and be known for who he is: a man falsely accused."

"He is a man, a husband, a father — not a politician, not a racketeer," defense lawyer Scott C. Williams said. "John Swallow did not commit any crime."

Prosecutors beg to differ.

In closing arguments Wednesday, they doubled down on their main theme — that Swallow played a pivotal part in a pay-to-play scheme inside the Utah attorney general's office.

They cast him as the moneyman, trainee and heir apparent to a criminal enterprise led by his immediate predecessor, Mark Shurtleff, designed to enrich their financial and political prospects.

Williams, on the other hand, stuck to his principal tune — that the state's star witness, Marc Sessions Jenson, was a veteran con man, who lied on the stand, and that the case was about politics.

He called Jenson "a career fraudster with 4.1 million reasons to lie," referring to the $4.1 million in restitution Jenson was ordered to pay from a 2005 criminal case and for which he eventually was sent to prison.

The jury of eight — five men and three women after four alternates were sent home — deliberated from about 4 p.m. until 7:30 p.m., before going home. Jurors will return Thursday at 9 a.m.

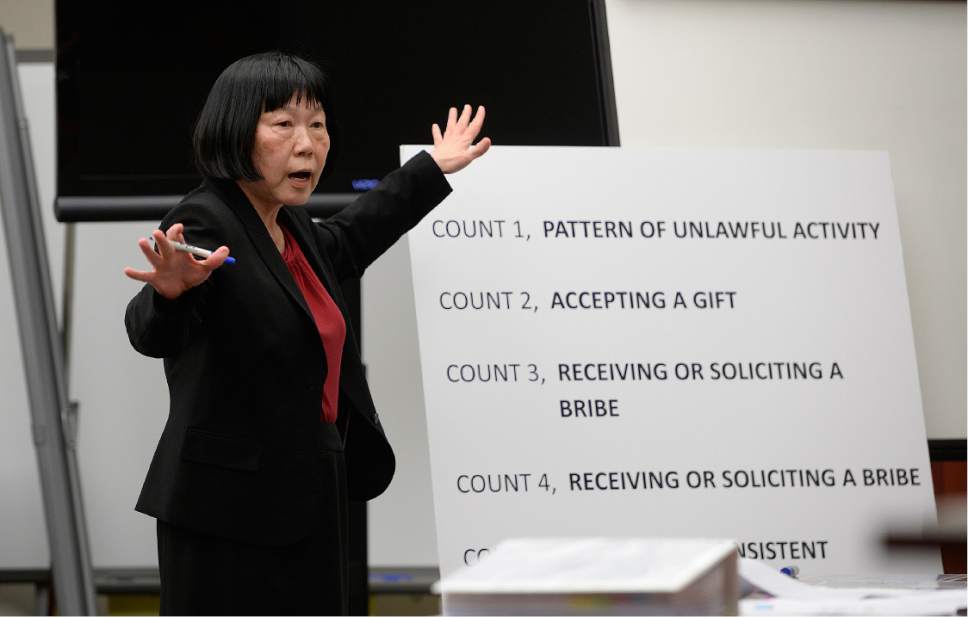

With one more charge dismissed Wednesday, Swallow faces eight felonies and one misdemeanor. The counts include racketeering, receiving or soliciting a bribe, tampering with evidence, misuse of public money, obstructing justice and falsifying a government record. Three other charges had been dismissed after another star witness, imprisoned St. George businessman Jeremy Johnson, refused to testify for the prosecution.

The charges stem from 2008, when Swallow was chief fundraiser for Shurtleff's campaigns, to 2013, when he succeeded Shurtleff as the state's top cop.

During closing arguments, attorneys summed up much of the evidence and witness testimony during the trial's three-plus weeks.

Deputy Salt Lake County District Attorney Fred Burmester hit hard on the role Shurtleff played in the alleged crime of racketeering, returning repeatedly to prosecutors' theory that Shurtleff led a triad composed of himself, Swallow and Shurtleff's late friend and "fixer," Timothy Lawson.

The purpose, Burmester said, was to harvest money from industries that might be on legal margins and subject to regulatory sanctions by offering "pay to play" assurances of friends in high places.

"The purpose of this organization, of this enterprise, was to advance the interests of its members both financially and politically," Burmester said.

Prosecutors have characterized Shurtleff as the leader, Swallow as the money guy and Lawson as the muscle, the one who went around telling people he was Shurtleff's Orrin Porter Rockwell, a legendary bodyguard and enforcer for early Mormon leaders.

Burmester also sought to bolster the credibility of Jenson, the state's first witness and on whose testimony the prosecution hung much of the racketeering charge. Jenson's restitution stemming from the 2005 criminal case was overseen by the Utah attorney general's office. Burmester said that gave Shurtleff, Swallow and Lawson an opportunity to extort him for money.

The prosecutor said Jenson's payments to Lawson, and trips the three made on Jenson's dime to the luxury Pelican Hill beach resort in California, amounted to "theft by extortion."

Williams attacked the state's case as a "house of cards" that prosecutors had built on the ever-changing, unreliable narrative from Jenson — who was in the courtroom gallery Wednesday — and on the desperation of state and federal agents who investigated only to have the U.S. Department of Justice's Public Integrity Section (DOJ-PIN) decline to press charges.

Williams reminded jurors that many of the state's own witnesses undercut Jenson's testimony that he had paid for trips Swallow made in 2009 to Pelican Hill with Shurtleff and Lawson because he was being extorted by the trio for money and favors.

That included two of Jenson's civil attorneys, former campaign staffers, several assistant attorneys general and Shurtleff's former chief criminal deputy.

Williams also showed jurors a blown-up copy of DOJ-PIN's letter to Utah's FBI office. It stated that after reviewing "the allegations of bribery and fraud schemes" investigated by agents, that an initiation of criminal proceedings was "not warranted."

"This case didn't have wheels at the start," Williams said.

Like prosecutors, Williams walked jurors through each count to remind them of witness testimony that he said disproved the state's case.

For example, a 2012 fundraiser, hosted by Timothy and Jennifer Bell, was not an attempt to solicit Swallow's help to win a lawsuit against Bank of America over the foreclosure of their home because a loan modification had been offered months before the event.

"There was nothing Swallow could do for them," Williams said, noting that the hosts had never been interviewed by the FBI.

Williams said prosecutors had similarly mischaracterized other pieces of evidence — from campaign-finance disclosures, attorney general's office time sheets and calendar entries — to fit their theory of the case.

They also had "plucked out" a handful of statements Swallow made in an interview with FBI agents and lieutenant governor's office investigators and offered them up as lies, the defense lawyer said.

The evidence, Williams contends, doesn't square with the state's storyline.

"When you force your narrative," he said, "it falls apart."

On Wednesday, as on nearly every other day of the trial, the benches on Swallow's side of the courtroom were full with family and friends.

A second prosecutor, Chou Chou Collins, forcefully challenged Williams' arguments, detailing evidence and witness testimony, saying the case was about power and greed.

At one point, Collins said, the state's misuse-of-public-money charge involved about $200 that went to fix a screen on Swallow's personal computer. Despite the relatively small amount, Collins said, "it's power, greed and corruption all together in that $200."

Shurtleff, Swallow and the Bells, she said, all benefited from their engagement over the Bells' illegal-foreclosure lawsuit against Bank of America and their fundraiser for Swallow. And Shurtleff freed Bank of America from the state's intervention in the lawsuit, meaning the question of whether it was illegally foreclosing on Utah homes was left for another day.

"What happened for the citizens of the state of Utah?" Collins asked. "Zero."

Shurtleff had been charged with multiple counts as well, but his case was dismissed.

As the jury deliberated, Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill said he was proud of the job his team had done on a complex, dynamic and difficult case.

"Our goal was to get it into court and advocate for our citizens of Utah," he said. "And that's what we did."

As for the state's decision to winnow four felony charges out of its case, Gill said that happens more often than the public may realize.

"We have ethical and legal reasons to not forward charges for which we don't have the evidence," he said. "It would be far more confusing to let [those] counts go forward."