This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

This morning, I was worried about my legs burning, not growing stiff.

I'm sitting on a stationary bike in a basement lab, as Ernie Rimer squats beside me to measure the distance between my toes and ankle, between my ankle and my knee, between my knee and my hip. He pulls out a protractor — a device that will give anyone a mild panic flashback to high school geometry — to determine what angles my feet and knees create as I'm sitting on the bike.

Utah's sports scientist insists this is all very exciting stuff: I'm Subject No. 2 in a study that will start as soon as he can start recruiting others, a study that Rimer thinks could change the way we think about ACL recovery.

I'm stuck more in the trappings of the moment: I'm wearing spandex in front of five people, and parts of my lower body are starting to fall asleep. I remind myself that progress — scientific, and other meaningful kinds of progress — takes time. It takes thoughtful design, precise measurements and critical interpretation of results. And real progress can make a difference.

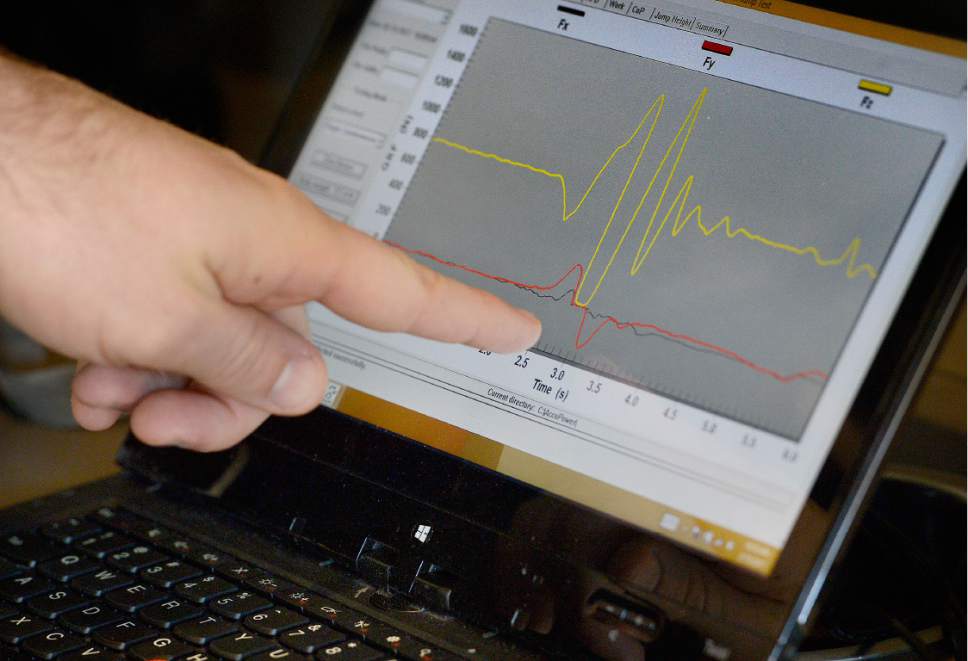

Rimer rises and heads to the computer monitor feet away. I get a moment to shake out the numbness in my legs. As I remount the bike, my specially designed shoes clip into the pedals, connected to wires that will send information back to the computer, right at Rimer's fingertips.

Subject No. 2's moment has arrived.

"Ready?" Rimer asks. "Now pedal."

Squeezing sense from data

In modern athletics, keeping track of performance is the easy part.

Athletes can monitor their heart rate, count their footsteps and log their diets with even average, check-it-on-my-phone means at their disposal. At the more complex level, athletic departments can now afford devices that measure strides and flight time with optic lasers and plates that send out 1,000 data points per second on how much force they take off and land with. There's technology that measures the reaction time of muscles, which can be used on a daily basis to tell coaches if their players are physically run down and need a break.

Big data, however, isn't the solution. In many ways, it's the problem. Athletic departments have been flooded with so much information, they don't know how to use it all.

"Everybody's strapping monitors on everyone," Utah men's basketball strength coach Charles Stephenson says. "I was talking to another coach from another school recently: He said, 'I've got four years of data all here on every athlete. It's not even going to matter.' "

Big data is a monolithic slab of marble — it needs a sculptor to shape it, to carve out a meaningful picture and give it substance.

A few years ago, Utah athletics realized it had a sculptor in house. He had worked with the U.S. Ski Team as a strength and conditioning coach for six years, and he was volunteering to help out the Utes as he worked on his PhD. After seeing what he could do and what he could bring, athletics officials decided to make "sports scientist" a full-time position at the U.

Rimer doesn't like to toot his own horn. He emphasizes that his role is not "over" anyone, that he simply works as a consultant to Utah's teams. But his role has helped build bridges and incorporate the latest scientific data in a way that the Utes never could before — allowing the programs to better compete against bigger names and bigger budgets.

"Ernie's expertise puts us even more on the cutting edge," Utah athletic director Chris Hill says. "It helps give us our best opportunity to be successful."

Looking for patterns

It takes a matter of minutes to see how a sportswriter falls far short of the physical bar set by a Division I college athlete.

Rimer runs me through some tests — measuring my broad jump on each leg, then the force of my vertical jump landings — and tells me how Utah's top leapers jump two to three times farther or higher than my best effort (which is understandable; I quit track in high school).

Scientific jargon and terms roll off his tongue quickly. Most people in Utah athletics talk about his energy, or how he'll talk you into a corner showing off a graph or a chart. He can also get rolling on some of his favorite topics —he's been known to sneak AC/DC and other classic rock references into his papers and presentations.

But today, Rimer is having me lean into his monitor in the Sorenson Performance Center, amid the Olympic-caliber gym equipment where his office is based. Within five minutes, he teaches me the basics of how to run some of the tracking software.

"Anybody can learn how to do this," he said. "That's why I don't let it define my job."

While some sports scientists at some universities are merely taking data, Rimer seeks to define it. If a coach or trainer comes to him asking about a piece of technology, he'll do research to determine if it's a practical and cost-effective acquisition. If someone asks him a question about performance, he'll try to design a study to find an answer.

Recently, strength coach Doug Elisaia asked Rimer to look into how to help the football team physically keep up with high-pace offenses, trying to maintain the ability to run and tackle well into the fourth quarter. Rimer has since performed a study on how single-leg cycling can help athletes run repeated sprints with less drop-off and he's looking into more answers — particularly now that Utah is planning on running its own high-tempo offense this fall.

"With our new OC," he says, "it's only going to get more important."

Bridging into academics

Rimer takes me downstairs to where he says "it's OK not to know all the answers." It's the office of Jim Martin, a kinesiology and nutrition professor, under whom Rimer is studying.

Martin is one of the world's foremost experts in the physiology of cycling with expertise in other athletic performance as well: He's worked with cyclists and sprinters from Australia, England and other countries around the world. Most recently, he's worked with Oracle Team USA to study the physiology of yacht athletes.

What kind of relationship did Martin have with Utah athletics since coming to the university 17 years ago? "None."

That was, until Rimer reached out, and started to work in studies influencing Utah athletics and using Utah athletes. As one of Martin's PhD students, Rimer has helped find mutually beneficial solutions for both the Utes and Utah's academic departments which could help produce relevant findings for the department.

Martin knows firsthand how sports scientists can be embraced — or ignored. He relates a story about how he once offered advice to Australia's sprint team, at the time one of the best programs in the world. They were offered science-based alterations to their training methods, but since they were producing world champions, they cast it aside. Before long, the French and British made the suggested changes themselves, and the Australians were world champions no longer.

"There's so many levels where an idea can break down and fail to be implemented," he said. "Sometimes you have to let it go, and just be confident in what you've done."

Facing wide budget gaps versus the top tier of the Pac-12, Utah is a program that's hungry enough to take science seriously as a possible competitive edge. Rimer has helped develop software that tracks every athlete's profile, and which can be updated by any coach or member of the training staff. He holds workshops in Microsoft Excel, teaching anyone who wants to know how to create spreadsheets.

Rimer often works closely with teams for a season or two: He was critical in helping Utah volleyball develop its offseason program this year, helping the Utes return to the NCAA Tournament. He met weekly with Kyle Whittingham this past football season. On a recent men's basketball trip, Rimer spent hours with a laptop simulating training sessions for the team, trying to determine how it would affect the Runnin' Utes' performance. He also is used as a recruiting point, and more than a few recruits have stopped by his office on official visits to chat about what he does at the U.

He's a popular guy.

"He's been really helpful in telling us what he sees in our practices, helping us keep our guys fresh," Whittingham says. "I think he's been a great addition to the department. He's been a valuable resource to us."

Creating a "hotbed"

Science is not Rimer's only specialty.

He was also tasked with implementing the High Performance Model, which he learned while working with the U.S. Ski Team. It's a system of leadership in which multiple areas share an equal voice: Utah athletics has a central performance team made up of in-game coaching, strength and conditioning, nutrition, psychology and sports science among them. Individual teams have their own performance teams with those components.

So when Rimer says he's not the boss of anyone, it's by a design he's helped create: Each part of each team is like "spokes on a wheel" — all critical to help keep things rolling forward, and each with an equal share of success.

Besides incorporating methods and practices that are backed by science, Rimer sees his job as creating an environment at Utah that creates other leaders. He wants Utah to become a place that creates disciples of the high performance model, and where young, ambitious people want to work.

"That's my vision of Utah: A tiny place that develops an exponential amount of talent," he says. "I hope that Utah becomes a sports science entity — a hotbed."

He sees promising signs of that already, as Utah's other strength coaches are pushing the boundaries of their learning. Stephenson, for example, is taking a business analytics course to further his understanding of how to handle big data. It matters little to him that he's already been a strength coach for 30 years.

He points to a lesson he took from Larry Krystkowiak, one that he thinks applies to Utah athletics more than ever as it embraces sports science: "Larry always says the edge is where learning takes place. If you're comfortable every day, you're not really growing. If you do something kind of hard, kind of scary, then you're learning."

Data into practice

My part in this is 18 seconds long.

My job is to pedal the bike at a consistent 200 watts in three six-second spurts — three trials, if you will — allowing Rimer to record the data. It is surprisingly difficult to maintain one set output: In the end, I ask another graduate student to tell me when I'm going the right speed, and try to keep steady.

I unclip from the bike, and look at my results: Rimer congratulates me for having a very symmetrical pedaling motion. My left leg generates a little more power than my right, but it's not statistically significant. Subject No. 2's output looks, well, normal.

The data could be used as part of a study put into motion by head athletic trainer Trevor Jameson. He wants to know how the body compensates for ACL injuries, and why athletes who tear ACLs go on to re-injure their knees or tear their opposite ACLs at a higher rate. I've never had an ACL injury, so my data could be in the control group.

Unlocking the biomechanical mysteries of how the body compensates for knee injuries could help change rehab methods or timelines, and could allow a lower rate of repeat injuries. Rimer says he'll get into the study "as soon as possible," looking for answers, or maybe finding new questions that he hasn't thought of yet.

"We're gaining confidence in our strategies," he said. "Everything we do is backed by research."

It's the scientific method: With more trial, Rimer hopes, comes less error.

Twitter: @kylegoon —

About Ernie Rimer

• First-ever Director of Sports Science for Utah athletics

• Ph.D student in U. of U.'s Department of Exercise and Sports Science

• Worked with U.S. Women's Alpine Ski Team from 2007-13

• Served as a strength and conditioning coach for Northern Arizona University

• Holds a bachelor's degree and master's degree from NAU

• Interned with Indianapolis Colts, Olympic Training Center, AFL's Arizona Rattlers