This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

As the clock winds down on Barack Obama's tenure as president, Utahns are awaiting what promises to be a monumental decision for the Bears Ears region.

While he could decide against using his "unilateral" powers under the Antiquities Act, many suspect he will set aside land in southern Utah — though less than the 1.9 million acres sought by a five-tribe coalition.

A scaled-back monument would most likely hew to the outlines of conservation areas proposed in Rep. Rob Bishop's Public Lands Initiative, or PLI, totaling about 1.3 million acres in San Juan County. Such a footprint would reflect, at least in part, the wishes of county leaders and residents whose recommendations were used to craft the San Juan portion of the PLI bill.

So is a compromise monument scenario something Utah and San Juan's political leaders can live with? Don't count on it.

"That's the wrong vehicle to get the right outcome," said Gov. Gary Herbert. "It's not the size so much as the vehicle."

In other words, public process is paramount for ensuring a Bears Ears conservation program Utah can agree to.

"You can put lipstick on the pig ... and say, 'Look, we are only going to do 1.4 million acres, isn't that what you want?' " Herbert said, but "the important part of this is it's not going to be done legislatively."

But on Friday, the sun officially set on Bishop's efforts to solve the Bear Ears question when the U.S. House adjourned without taking a vote on his PLI bill, which would have affected 18 million acres of public land. The bill's failure prompted conservationists to renew their calls on Obama to designate a monument.

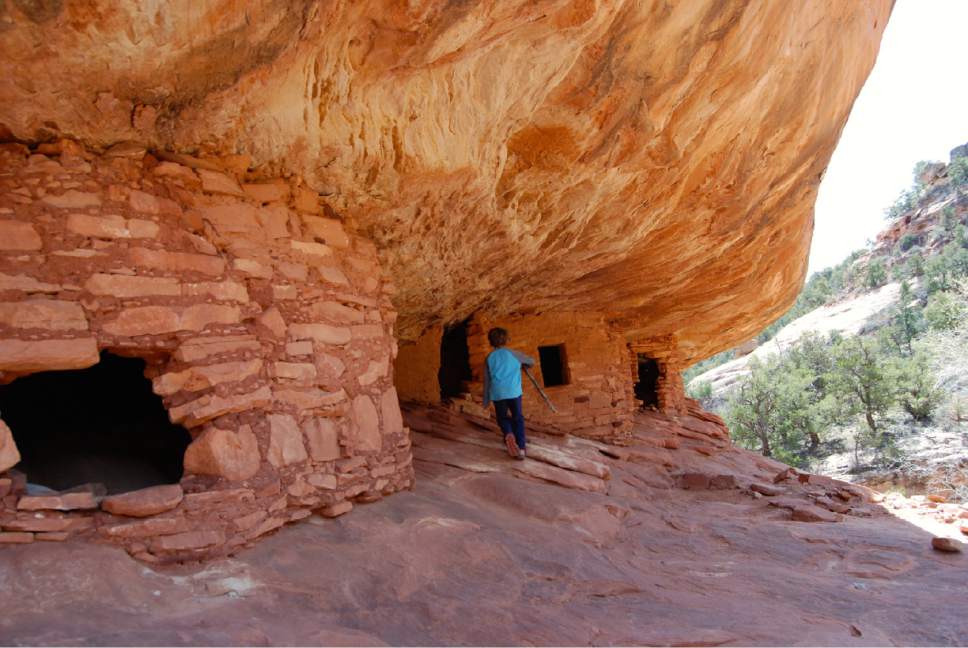

"While we always preferred a legislative solution, this executive action is precisely what Congress envisioned when it delegated to the president the authority to create national monuments," said Josh Ewing of Friends of Cedar Mesa. "With skyrocketing visitation [to the Bears Ears region] without management resources, continuing looting and vandalism, and the bull's-eye of out-of-state energy developers, we don't have 113 more years to wait for Congress to get the job done."

Obama has used the Antiquities Act to designate 12 landscape-scale monuments in the West, covering 4 million acres, but so far has not acted on monument proposals in Arizona and Utah.

Obama "has touted the fact that he has not done it where there has not been some desire to have a monument," Herbert said. "So this would be first time that, if he does it, where we have none of our Congressional delegation supports it, the governor doesn't support it, the Legislature is 90 percent opposed to it. The people in the area are mostly opposed. The Indians are at best divided."

He referred to last month's unsuccessful re-election bids of Ute Mountain Ute Council members Malcolm Lehi and Regina Lopez-Whiteskunk.

"Those who were pushing for a national monument were replaced in office and one of the reasons for it was because they thought there was too much emphasis on the monument," Herbert said.

Monument backers say other issues were at play in those tribal elections and point out that Kenneth Maryboy, a former county commissioner who supports the monument, was elected president of the Navajo Tribe's Mexican Water chapter.

The San Juan County Commission remains deeply opposed to a national monument, but acknowledges that the region's cultural sites, scenery and geological wonders are treasures worthy of preservation — as long as public access and traditional uses are also preserved.

At a county commission meeting last month, Commissioner Bruce Adams said he had heard from congressional staffers that the White House could be considering a monument that is in line with what San Juan's citizens advisory council put forward in the PLI.

That prospect pleased him at that time — but when asked Thursday, he said he would still oppose such a designation and would hope Congress rescinds it.

"This needs to be a locally driven thing, not top down, so we engaged with Rob Bishop," said Adams, a Monticello rancher. "We might end up with the conservation areas, but without local buy-in, we can't support that."

Bishop and Rep. Jason Chaffetz launched the PLI process in 2013 to forestall Obama's anticipated use of the Antiquities Act to designate a big monument in Utah. They said a legislative approach was the only way the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition could achieve two major provisions of their monument proposal: wilderness designations and tribal co-management that's on equal footing with the federal agencies.

The current version of the PLI would designate 4 million acres of new wilderness across eastern Utah, but provides nothing for Bears Ears tribal co-management — just a single seat on a 10-seat "advisory" board, basically on the same footing as motorized recreation and livestock grazers.

The congressmen last month asked the coalition to provide legislative language reflecting the tribes' desire for management authority, but nothing has been forthcoming.

"I like the idea of co-management. The president, with or without the Antiquities Act, cannot produce it," Bishop said in a prepared statement. "It is frustrating that efforts to work with people who claim a great interest in this area are continuously rebuffed with arguments that parrot special interest groups. Ironically, if [the inter-tribal coalition] is banking on a monument, they will never get the co-management they want. We're willing to give it to them."

The tribal coalition leaders, who hail from Navajo, Ute and Puebloan tribes, say they have tried to work legislative angles. But Bishop and Chaffetz did not take their input seriously, they said, so they took their proposal straight to the White House, where they have received a receptive ear.

Meanwhile, the wilderness and national conservation areas the Utah congressmen proposed in the PLI leave out the western reaches of Cedar Mesa, whose remote canyons harbor ancient archaeological sites — as well as uranium deposits that industry hopes to tap.

The bill also fails to safeguard White Canyon and its various drainages, Moki Canyon and Bluff Bench, according to Friends of Cedar Mesa, a pro-monument stewardship group based in Bluff.

"If the monument is any less than what the tribes proposed, there will be important archaeology that is left unprotected," said Ewing, the group's executive director. "There are very good reasons for the boundaries proposed by the coalition. A monument smaller than that is somewhat likely because [Interior Secretary Sally] Jewell came out here to listen and lot of people were saying make it smaller. I'm guessing they are taking that local input under advisement. I am hopeful they won't throw out local input from the Bluff community."

This tourism-oriented town at the southern gateway to Cedar Mesa is far more receptive to a monument than Blanding and Monticello.

Many San Juan County residents spoke out against a monument during Jewell's visit to gauge local sentiment in July. But plenty of tribal members from Utah and adjoining states told Jewell a monument is needed to keep ATVs, looters and industrial development away from places that are valued for gathering medicinal herbs and firewood, reverent spiritual practices, its awesome beauty and ancestral connections.

Tribes and conservationists are not the only ones voicing favor for a monument.

Interior has received endorsements from the outdoor industry, education groups, archaeological societies and even health professionals.

"As a family physician descended from the Anasazi, I see Bears Ears as priceless not only for its history and beauty, but also for its potential to heal and prevent disease," said Garon Coriz, a member of the Santa Domingo Pueblo who practices in Salina. He is among the 180 medical professionals who signed a Dec. 7 letter declaring a monument would promote physical and cultural healing.

"There are the very real psychological benefits from taking an action that addresses the traumatic historical disenfranchisement of Native Americans," the letter states. "In addition, a growing body of research shows that time spent in the kind of undisturbed natural settings offered by the Bears Ears area fosters emotional health in general, decreasing anxiety, reducing physiological response to stress, and dramatically enhancing concentration, creativity and problem-solving skills."

On the other side, Utah's Wildlife Board, agricultural interest groups, the Utah School Boards Association, and the Legislature have passed resolutions condemning the proposed monument for its potential to step on state prerogatives and harm rural communities.

Twitter: @brianmaffly