This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

In "a very close call," a Salt Lake County board denied an ACLU appeal Tuesday requesting the release of body cam footage from a police-involved shooting that critically injured then-17-year-old Abdullahi "Abdi" Mohamed.

The ACLU said in news release Wednesday that it would fight the board's decision in yet another appeal.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Utah appeared before the Salt Lake County Government Records Access and Management (GRAMA) Appeals Board last week to argue for the release of body cam footage from two officers, a surveillance video and at least 11 crime scene photos, which had been classified as "protected" by the county.

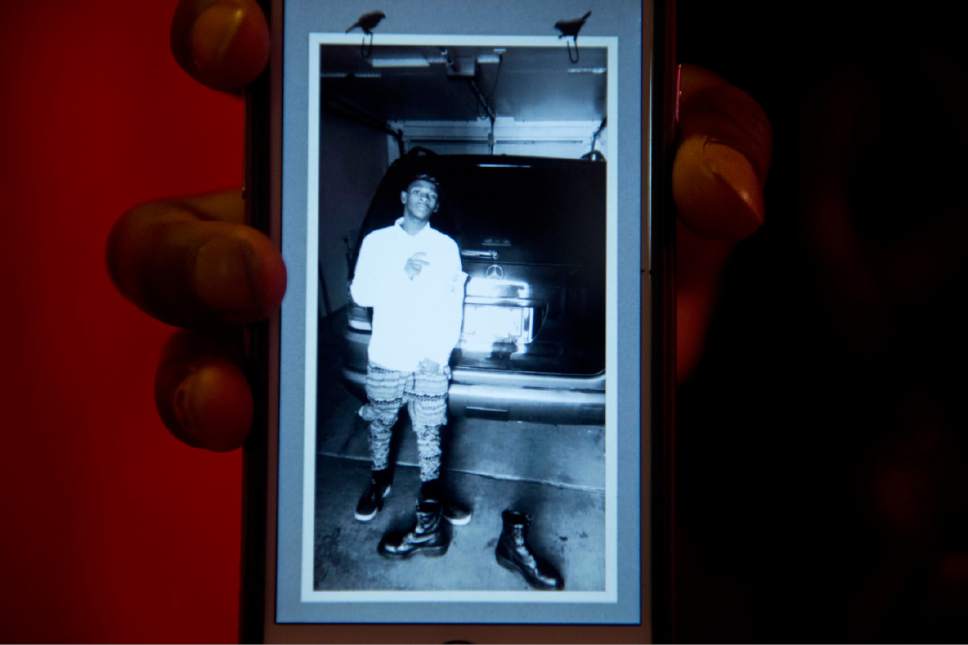

Salt Lake City officers Kory Checketts and Jordan Winegar shot Mohamed, a Somali refugee, four times on Feb. 27. The teen survived after going into a medically induced coma and spending weeks in the hospital.

While there is "significant public interest ... especially with the numerous cases nationwide of young African-American men being shot or killed by police officers ... [and] in ensuring the transparency and review of the actions of public officials," the appeals board wrote, the interest of ensuring Mohamed has a fair trial outweighs the issue of public interest.

The county is "very pleased" with the board's decision, Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill said, adding that its wording "recognizes the nuanced complexity of this issue."

"The question is not whether release of the records would deprive a person of a fair trial, but rather whether it would create a danger of depriving a person of a fair trial," the appeals board denial states. "The board finds it would."

The ACLU "appreciate[s] the time and attention the board members dedicated to this matter," said David Reymann, a Salt Lake City-based media attorney who assisted the ACLU with the case at no charge, in the release. "[But] we respectfully disagree with their conclusion."

As of Wednesday, the ACLU hadn't decided whether to file its next appeal to the State Records Committee or directly to district court, it said, but the group plans to make that decision "sooner rather than later," according to staff attorney Leah Farrell.

In August, Gill's office determined that the officers were justified in their use of force and filed charges against Mohamed in juvenile court, alleging aggravated robbery, a first-degree felony, and drug possession with intent to distribute, a second-degree felony.

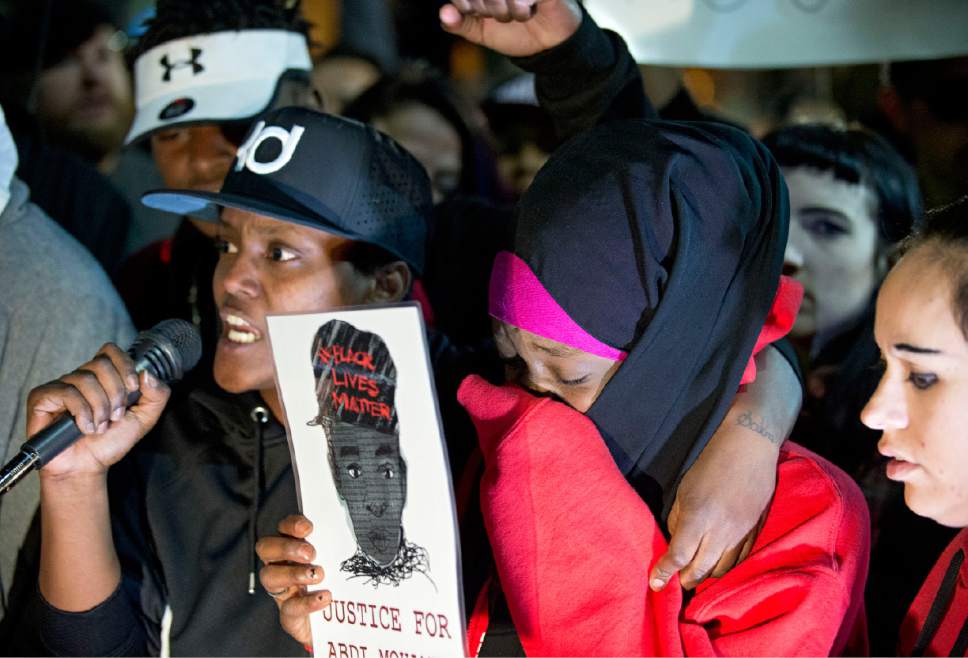

The announcement sparked outrage and protests from some people, who called for Gill and Salt Lake City Mayor Jackie Biskupski to resign.

Last month, the Salt Lake City Police Civilian Review Board issued a report stating that Checketts and Winegar's behavior during the incident was "not within" policy.

But "the Police Citizen Review Board's report does not contradict statements by Mr. Gill in August," the appeals board stated in its denial, "as the [city] board's decision was based on city policy and Mr. Gill was reviewing state law."

The ACLU originally submitted public records requests in May to the police department and the district attorney's office for the officer's body cam footage, requests that were refused.

The appeals board stated in the denial that releasing the "protected" records could interfere with a fair trial for Mohamed by tainting the testimonies of potential witnesses — a point brought up by Deputy Salt Lake County District Attorney Darcy Goddard at last week's hearing.

Mohamed's case is set for a preliminary hearing Jan. 23 in 3rd District Juvenile Court. If the case stays in juvenile court, Mohamed could be incarcerated until he is 21 years old. If the case is moved to adult court, a conviction on the robbery count could lead to a prison sentence for up to life.

Reymann argued that the Government Records Access and Management Act mandates the video's release and that there is no legal justification for keeping the video private. The public deserves to see the video firsthand, he said, so it can hold government officials, like Gill, accountable.

If government bodies are going to make "selective" decisions about when something is released, Reymann said, police "might as well not be wearing body cameras."

But Goddard argued that the footage depicts incriminating evidence of a private juvenile civilian, and its public release would follow Mohamed for the rest of his life. She also said the video could bias a jury if the case ends up in adult court.

"The fact that [Mohamed] or his attorney have not had an opportunity to comment on this GRAMA request weighs against the disclosure of the contested records," the board's denial said.

Goddard said last week that a judge should be the person authorizing the documents' release, and that the county opposes the video's release because it cares about protecting Mohamed's constitutional rights.

Reymann said at the hearing that a judge does not have the authority to release such records — "that's this board's job." He described the appeals board's decision Wednesday as "disappointing."

Twitter: @mnoblenews