This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

White Mesa • Concerns about possible water contamination have some residents of a remote Utah town considering relocation.

Data suggest that an aquifer located below the White Mesa uranium mill contains multiple contaminants, but there's disagreement about whether the pollution is related to natural hazards, or coming from the current mill or past mining and industry in southeastern Utah.

And regardless the source, residents say, state, federal and even tribal leaders don't seem concerned about the potential threat to the health and way of life of the just-under 300 people who call White Mesa home.

"You're giving us all this information, but what's really going to happen?" asked resident David Yearicks during an October town hall to address the contamination. "If the answer is the community fighting for change ... that sounds like a Band-Aid over a gushing wound."

Scott Clow, environmental programs director for the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, said the aquifer that underlies both the town and the White Mesa uranium mill is known to be contaminated with chloroform, nitrate, chloride, fluoride and multiple heavy metals, including uranium. Over the past seven years, he said, samples from the monitoring wells surrounding the mill indicate that heavy metals concentrations are increasing and that the water is becoming increasingly acidic.

The Utah Department of Health has recently recruited volunteers from White Mesa to participate in a study of residents' exposure to heavy metals, which are believed to be a problem in communities throughout the Four Corners region due to the area's historic mining activities. Megan Broekemeier, a health department educator who helped recruit in White Mesa, said 25 people — about 10 percent of the town's population — agreed to participate.

But the state has declined to investigate the water itself, Clow said, even though "it seems pretty obvious to us that [contaminants are] coming from the tailings cells."

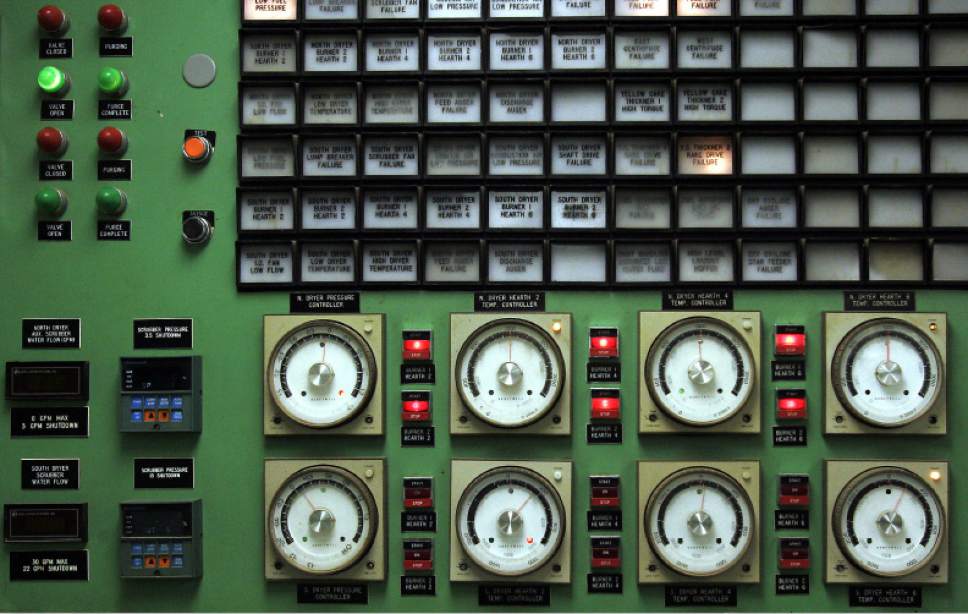

The mill, designed to process uranium ore, extracts uranium from other uranium-bearing materials when supplies of natural ore run low. It accepts waste from the Department of Defense as well as from the Environmental Protection Agency.

The mill's Radioactive Materials License permit has been under review since 2007, Clow said, and in the meantime, the EPA has left oversight to Utah while sending waste from Superfund and other clean-up sites around the country to White Mesa.

EPA spokesman Rich Mylott said the agency reviews the state's work on the White Mesa Mill as requested.

The mill's permit should be finished by the end of the year, according to Phil Goble, manager of the state's Uranium Mills and Radioactive Materials section. The state's review has hit snags, and the permit has been revised to accommodate public feedback.

"It's not like we've been just sitting on it since 2007," Goble said. "We've done a ton of work on it. It's over a thousand pages of stuff."

Meanwhile, monitoring at the mill has actually increased, Goble said.

In 2004, he said, there were 11 groundwater monitoring wells at the White Mesa site that were tested for five possible contaminants. Today, he said, there are 120 wells on the site, with some tested for as many as 38 possible contaminants. He said the state requested more monitoring as the mill expanded its operation over the years.

"There's nothing — no smoking gun that there's this big problem," he said. "They're in compliance."

From the state's perspective, Goble said, Energy Fuels Resources — which owns and operates the White Mesa Mill — has gone above and beyond to help the White Mesa community, even donating the very community center where October's town hall was held. The residents' complaints, he said, amount to "biting the hand that feeds."

There are known plumes of contamination in the aquifer immediately beneath the mill, Goble said, but concentrations of chloroform and nitrates have dropped significantly since mitigation efforts began. And though the water has become more acidic, he said, it's happened throughout the aquifer — not just downstream of the mill, where one would expect pollutants from the mill to have an impact.

Clow believes the contamination that underlies the mill is the result of leakage from the tailings ponds where waste materials have been stored since the mill opened in the 1980s. The ponds were sealed with liners that had an estimated life span of 15 years — but 36 years later, some of those same liners are still being used, he said.

David Naftz, a hydrologist with the USGS who worked on the study of the White Mesa site, said he and his colleagues found elevated concentrations of uranium and other elements in some of the soil and on plants near the entrance to the mill, and contamination in a nearby spring that appeared to be associated with the mill's operations.

This was likely the result of wind-blown dust from the mill or from trucks bringing ore and other materials to the mill, Naftz said. When it rains, he said, that dust could wash into the spring.

They found little evidence of groundwater contamination that could be tied to the mill, but that doesn't mean it hasn't happened, Naftz said — groundwater moves slowly in this region.

"Even if the mill were contaminating the groundwater, it would be a while before it shows up at those [test] wells," he said. "If something leaked from a tailings pond today, it could be decades before it would show up off-site."

Even if the groundwater is contaminated, Goble said, it's not going impact the town's drinking water, which is sourced from an aquifer separated from the contaminated water by a 500-foot layer of clay.

But Colin Larrick, a water quality specialist with the Ute Mountain Ute Environmental Program, said the mill has drilled a well of its own into the deep aquifer, and that could convey contaminants into the lower formations.

And it's not just the drinking water that has raised concerns, said Malcom Lehi, a tribal councilman representing White Mesa.

The contaminated aquifer feeds several nearby springs that the tribe uses for spiritual rituals, he said. If those springs become contaminated, the tribe would have to cease practicing a significant part of its cultural traditions.

Curtis Moore, vice president of marketing for Energy Fuels Resources, said the contamination in the upper reservoir is likely related to the land's historic use prior to the mill's construction. Energy Fuels is assisting the state in addressing those issues, he said.

For many residents in White Mesa, this is all difficult to understand, said Crystal Morris, who has lived all her life in the town. In many cases, she said, they don't have the education to comprehend what the experts are telling them, leaving them feeling confused about whether the water in their community is safe.

"We want answers — is this going to be taken care of?" she said. "They can't give us answers, but they've known about it all these years."

The community's drinking water does have problems, Goble said, but the issues — primarily the presence of sulfur — are purely aesthetic and appear to be related to contaminants naturally present in the area's groundwater.

"They have complained about the smell and the taste of it for many years," he said.

The water currently meets drinking quality standards, but that could change, according to Clow, because an old well that used to serve the community is about to be brought back online. That well contains natural concentrations of arsenic, and once it begins operating, the community will need to install a modern water treatment plant.

Manuel Heart, chairman of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, said the tribe was recently awarded a $9.1 million grant from the USDA to improve the community's drinking water. $2 million of that will go toward building a modern water treatment plant at White Mesa, he said.

Morris said she was dismayed to learn that only $2 million would make it to White Mesa. She and other residents questioned whether that amount would be adequate to sustain such a water treatment plant, and whether tribal leaders have this community's interests at heart.

During the town hall, Yearicks asked tribal leaders whether it was time to begin considering abandoning the town.

"In reality, there's no amount of money that can fix this," he said. "Do you think the answer is the relocation of community members?"

Morris, who was diagnosed in 2010 at the age of 35 with a rare form of multiple myeloma, said she has considered relocating her family.

At the same time, she said, she worries about moving her three kids away from the slow pace of White Mesa and into a city where the dangers might come in the form of drugs and gangs.

Talk of relocation is difficult for residents, Yearicks said.

"People love White Mesa, because it's Ute land," he said. "It's got families, memories, so it's difficult."

But it may be necessary if nothing changes, he said.

"I don't want no one to feel sorry for us," he added. "I want to fix the problem. I want a solution."

Twitter: @EmaPen