This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Mormons have embraced the City of Brotherly Love with a passion, and the attraction seems to be mutual — even though the LDS project includes a towered temple most Philadelphia residents won't be able to enter and a mini-City Creek development that some won't be able to afford.

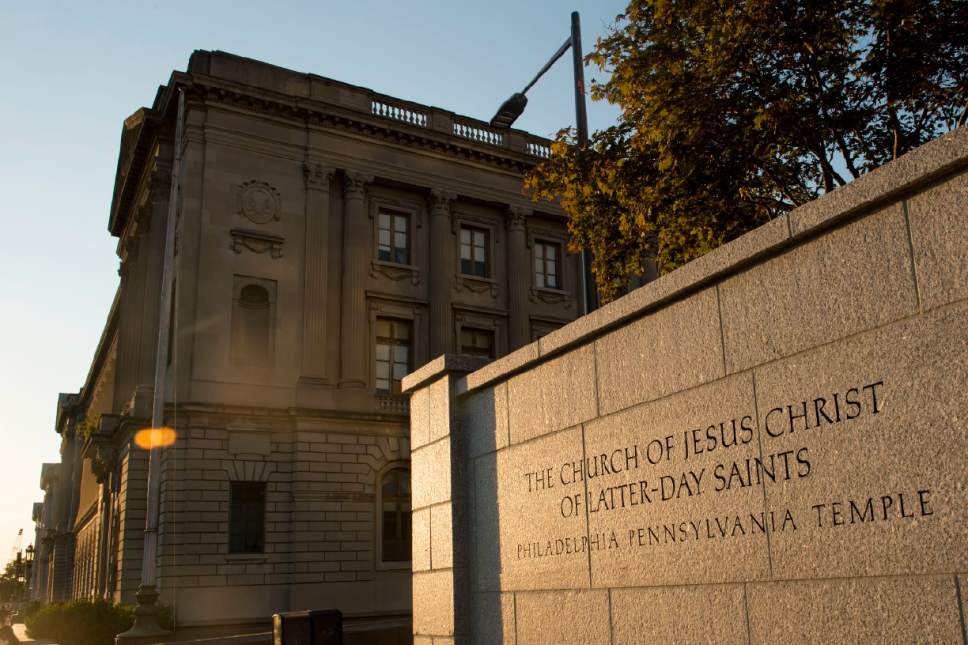

Completing the Mormon temple and a nearby stake (regional) center in the heart of the historic city, with a 32-story apartment complex going up across the street, has been a "glorious move for us," says Jonathan Stephenson, LDS public-affairs director in Philly. "The overwhelming welcome has been wonderful."

Key city officials are adding their amens.

The LDS Church was "great in the way it handled the design, rules and regulations for zoning in that area," winning the approval of every neighborhood association, says James Cuorato, head of the city's Redevelopment Authority. "The residential development is quite attractive, really ideal for that location, and fits well with the surrounding area."

No significant opposition emerged — not from penny-pinching Mormons fretting about the use of church funds for the commercial component. Not from members of other faiths leery of influence by a little-known religion some find foreign. Not from community activists eager to bring their own development visions to a vibrant downtown.

The same cannot be said for other Mormon building efforts stretching from Boston to Orlando, Fla., to Portland, Ore. Even in Salt Lake City, home to the church's headquarters, critics have lambasted LDS projects — from its new Main Street mall to its pedestrian plaza.

In Philly, though, the Mormon effort has had "a healing influence on the whole city," a city planning commissioner wrote in an email to LDS officials. "This property was vacant for years, a kind of hole in the middle of that part of the city ... a kind of no-man's land."

The Utah-based Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, he wrote, "has made downtown whole again."

For the past month, tens of thousands of curious onlookers from Philly and surrounding environs have streamed through the temple's interiors, marveling at its architectural details and learning of its religious purposes.

Such explanations "remove some of the mystery as to the purpose of the temple, how it's used and when it's used," says David Gutin, an area Jewish leader who toured the structure with other interfaith leaders.

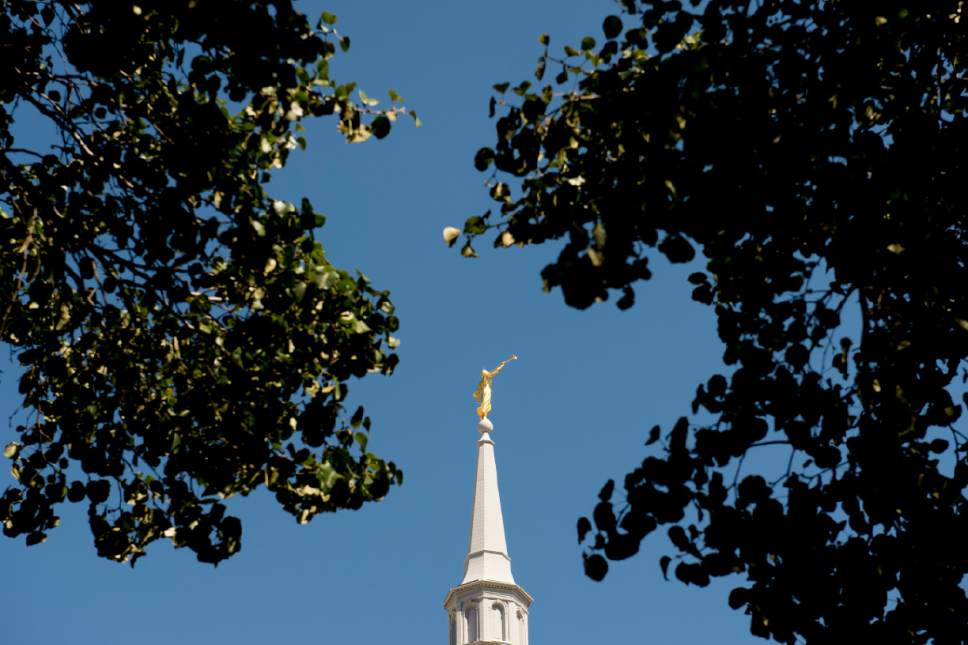

On Sunday, Henry B. Eyring, first counselor in the LDS Church's governing First Presidency who was baptized at age 8 in Philly's first Mormon chapel, will dedicate the church's 152nd operating temple. After that ceremony, only devout Mormons will be allowed into its sacred space to take part in the faith's highest rites, including eternal marriage.

The just-completed Mormon meetinghouse nearby, however, will be home to several LDS wards, or congregations, and open to community events and all visitors. And the 490,000-square-foot housing complex hopes to attract diverse tenants and shops.

Having these Mormon blocks in the center of town "can only be an asset to Philadelphia," Gutin says. "The sense I have is that the Mormon faith encourages people to do good and be helpful to others. It's a win-win for all of us."

With such a positive response, the question becomes: Could the combination of tax-free religious construction and taxable development be the church's pattern for future temple sites?

—

Long but subtle presence • Mormonism views Pennsylvania's founding as an essential element in its own past, though the Eastern state was established long before LDS beginnings in 1830.

"Our historical roots go back to William Penn, absolutely," Stephenson says. "As church members, we revere William Penn as one historical figure who paved the way for religious freedom."

Pennsylvania was the only colony that "practiced religious tolerance," he explains. "It's the Quaker way. That mindset is still active in this community."

Though many significant events from LDS history took place in Pennsylvania — the first Mormon, Joseph Smith, was baptized there — it wasn't until 1938 that the first LDS chapel appeared in Philly, says Stephenson, a lifelong Mormon who grew up there and earned a degree from the University of Pennsylvania.

With the help of missionaries arriving from the West, through the decades Philly Mormons built a strong, though small, community.

By the 1970s, the once-vibrant downtown — like other central cities across the nation — began to empty out and, seeing the trend, the LDS Church sold its buildings in the home of the Liberty Bell, including the 1938 chapel. A decade later, Mormon authorities changed course, reinvesting in the city's core.

After Mormon leaders announced plans in 2008 to erect a temple in Philly, they huddled with city officials and civic leaders, listening to any concerns about the project.

"From day one, the church wanted to make sure it was doing things the right way," says Cuorato, the RDA chief. "It was not trying to take advantage [of anyone] as far as the land goes. It is prime land."

At the time, two parcels were available — both parking lots — but with different owners, Stephenson says. The one that eventually would house the temple came at a reasonable cost, but when LDS officials approached the owner of the future home of The Alexander apartments and shops, he "jacked up the price."

During the two years it took to negotiate all the approvals for the temple, the housing parcel went into foreclosure, the LDS spokesman says. The bank then offered it to the church "for a tenth of the previous owner's price."

With both blocks in hand, permits for the development sailed through in 30 days, Stephenson adds, quoting a stunned lawyer involved in the quick process as saying, "Whatever you Mormons pray for, you get."

—

Future trend? • Built on a rise near Beverly Hills in 1956, the Los Angeles Temple signified the LDS Church's arrival and presence in that upscale area. Two decades, later, however, the neighborhood declined.

After that, Mormon officials seemed to favor affluent suburban sites for their most sacred structures, trying to assure permanently secure and valuable locations. At times, this strategy ran into resistance from wealthy neighbors.

If the Philly — or downtown Salt Lake City — model of pairing a temple with shopping malls and housing works, it might be replicated in the future.

The Alexander — named not for the famous patriot of "Hamilton" musical fame but for Alexander Milne Calder who designed the 37-foot-tall statue of William Penn that tops Philly's dazzling City Hall — is all rentals, including 258 high-rise apartments and 13 town houses.

"It is billed as a 'luxury' building, meaning an indoor pool, exercise room and other amenities," Stephenson says. "I would guess a two-bedroom apartment will run about $2,500 per month, which is the going rate for such in the neighborhood now."

The first two stories will feature shops such as boutiques and bakeries, drugstores and dry cleaners.

"Everyone respects the fact that the Mormons came in and built this temple ... which is jaw-droppingly beautiful," Cuorato says. "They played by the rules and did things the right way."

And it paid off.

"From an investment standpoint, we like the growth we see in Philadelphia's downtown," says Dale Bills, a spokesman for the LDS Church's real-estate arm. "The Alexander will be a long-term hold for us, so we're looking forward to being part of the neighborhood for years to come."

Now, the Catholic Archdiocese of Philadelphia, which takes up a city block across from the LDS grounds, hopes to follow a similar route.

"We just saw a master plan," says Cuorato, who also is president and CEO of the Independence [Hall] Visitor Center (and a Catholic), "the archdiocese is planning to rebuild the entire block, except the basilica, and include a commercial development."

Such exchanges and opportunities seem apt, Stephenson says, for such a religiously rich city — where a gold-leafed Angel Moroni aims his trumpet directly at the founder of it all, astride the famed City Hall.

Twitter: @religiongal