This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Rachel Jeffs didn't even know where she was living. Somewhere in Idaho is all she knew. She never learned the address.

She didn't have a reason to learn it. She and the other women there were not allowed to leave, Jeffs said, or even to go outside during daylight.

"We could go outside at night on the deck and stuff, but not during the day," Jeffs said. "And we were supposed to sew — everybody — and stay in the house and clean and make meals."

Jeffs was living in what the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints calls a "house of hiding." Her caretaker there, she said in an interview Wednesday, was her uncle — Lyle Jeffs. Former FLDS followers suspect he is now living in such a house — somewhere.

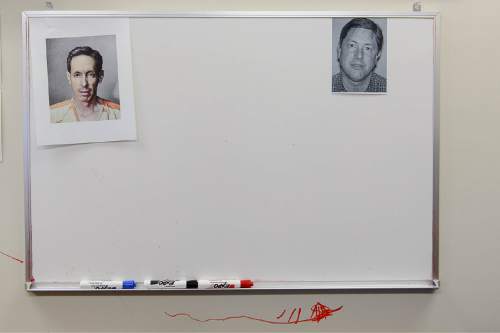

The house of hiding network was one reason federal prosecutors asked Lyle be kept in jail pending his trial in October on two counts related to food stamp fraud. U.S. District Court Judge Ted Stewart released Lyle from jail earlier this month. Jeffs became a federal fugitive on June 19 when he ditched his GPS ankle monitor. A warrant has been issued for his arrest.

"He's got people that will buy him a house in a heartbeat," said Matt Jeffs, one of Lyle's sons.

Interviews and court documents describe the Houses of hiding as being what the name implies, though law enforcement has located some of them over the years. Court papers mention investigators finding such houses in Las Vegas, San Angelo, Texas, and one described as a "remote timbered wilderness area... 25 mountain miles from the nearest small settlement."

Court documents also have described what appears to be a House of hiding near Custer, S.D., not far from where the FLDS has a compound. The rental home outside of Pocatello, Idaho, where authorities found nine FLDS boys living in 2014 under the supervision of a caretaker later convicted of misdemeanor counts of child abuse, also has been described by former followers as a house of hiding.

Lyle's older brother, FLDS President Warren Jeffs, created the House of hiding network about 2004, according to interviews, when he was running from civil lawsuits and investigators. That's about the time the FLDS was purchasing ranches in Eldorado, Texas, and Pringle, S.D, and a small compound in Mancos, Colo.

Those properties were called "lands of refuge." The most devout and worthy members of the faith were moved there. The Houses of hiding were meant for a slightly lesser group for whom there was not yet enough lodging to move to the ranches or who needed to improve their standing first. The Texas, South Dakota and Colorado properties soon were discovered by law enforcement and journalists. The houses of hiding remained secret. They were either rented or purchased by men or businesses loyal to Warren in places that were rural or at least had high fences.

Some of people on the ranches were moved to houses of hiding by 2006, Rachel said, when the search for Warren, who is her father, intensified and he needed to hide people who could testify against him. That included, Rachel said, the sons and daughters he molested.

"Really, they are the evidence against him," Rachel said, "and that's why he so carefully keeps us afraid of the law."

Prosecutors have said one of the people who helped manage the houses of hiding was Nephi Steed Allred, who is one of Lyle's co-defendants in the food stamp fraud case. A brief from prosecutors says Allred helped move Warren's family, created business names to register the properties and "facilitated telephone management with people in the houses of hiding...."

Lyle started moving his family to houses of hiding in and near Las Vegas in 2006, said Matt, after hopping aboard an ATV and driving away from FBI agents trying to serve him with a subpoena. Matt was 13 at the time.

For a couple weeks, Matt lived in a house on Rainbow Boulevard where the FLDS built a clinic on the top floor. Some of Matt's siblings were born there. Then Matt and other members of Lyle's family moved to a home in Mount Charleston, Nev.

The home had a 13-car garage with a boxing ring, Matt said. The FLDS tore down the ring and converted the garage into bedrooms for the boys. Bunk beds were erected in the massive master bedroom where the girls slept, he said. Milk cows were put in the back yard. Eventually, Matt said, about 100 people lived there. They were either Lyle's family or families whose husbands and fathers had been evicted from the FLDS.

"It was normal life to me," Matt said.

There was a third house in Henderson, Nev., Matt said, with an indoor swimming pool. It was strictly used for baptisms, he said.

Lyle, Matt said, lived in yet another house — in Boulder, Nev. His sons and then-nine wives took turns visiting him there. Lyle assigned men to be caretakers to watch over the other homes and deliver food and other supplies to them.

Matt said everyone was told they were hiding from law enforcement and from private investigators Sam Brower, who went on to write the book about the FLDS called "Prophet's Prey," and Andrew Chatwin. To stay ahead of them, the FLDS frequently moved the houses of hiding and the people living there. About 2008, Matt and other Jeffs were moved to houses of hiding in Colorado.

That was the one place Matt says he encountered law enforcement. The occupants were burning logs in the yard. Neighbors must have seen the smoke and called the fire department, Matt said.

One person was designated to stay and talk to the police and firefighters, Matt said. Everyone else did as they were trained to do. They ran into the house, locked all the doors and windows and stayed out of sight. The responders left without ever checking in the house, Matt said.

Matt had uncles and cousins living in houses nearby. At one point, Matt said, Lyle told him that everyone with the last name Jeffs had been moved out of the FLDS' traditional home in Hildale, Utah, and Colorado City, Ariz., collectively called Short Creek.

The family trickled back to Short Creek following Texas authorities' 2008 raid on the ranch near Eldorado. Matt said legal fees were piling up and the FLDS couldn't afford to ship people and food to so many far-flung places. But not all the houses of hiding were abandoned.

Rachel said she was told in 2012 that she needed to repent. She wasn't told why. She was forced to leave her five children with her husband's family and she was sent to the house of hiding in Idaho. Lyle had temporarily been removed as the Bishop of Short Creek and sent to Idaho, too.

"When I went there, it was really just a bunch of my father's family — wives, girls and some of his sons," Rachel said. "And Lyle was in charge of all of us."

While the women sewed, the men and boys worked in a wood shop on the property, Rachel said. Lyle would bring groceries, lead scripture lessons in the morning and evening and tell the people there what they needed to do to become worthy again, Rachel said.

She was there a few weeks before being allowed to return to Short Creek. Later, Rachel said, she and her children went to a house of hiding near Pikes Peak in Colorado. There, the FLDS had a camera and motion sensor facing the road. Every time a car approached, an alarm sounded in the house. Someone would look at a monitor to see if the car was one of the few neighbors or police.

In both the Idaho and Colorado homes, one person had a cell phone. The occupants in the houses of hiding were only allowed to call a few numbers and could not discuss with the caller where they were.

Rachel assumes Lyle is with one or two other people living in some house of hiding that only a few in his circle know of. Soon a driver will move him to another house in a vehicle owned by a third person.

"It's very much thought out how to hide people," Rachel said.

Twitter: @natecarlisle —

More on the houses of hiding

In 2007, former Warren Jeffs loyalist Wendell Musser told The Salt Lake Tribune what it was like being a caretaker for three such homes in Colorado, and the mistake that cost him his marriage. https://shar.es/1JV57W