This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Sandy • Weldon Angelos is 36 years old, with no job and no home of his own. He bunks at his sister's house, only recently got his license and that iPhone remains a mystery to him.

But cut him some slack. He's been in prison for 12½ years and must rebuild his life. Truth is, he was supposed to be behind bars longer, years longer, decades longer.

But Angelos enjoyed a sudden reversal of fortune.

He would have been in his 70s by the time he finished serving a mandatory 55-year sentence on federal gun and drug convictions, but Angelos was abruptly released last month.

Several weeks later, he was enjoying himself at a party in his sister's backyard, surrounded by people who worked hard for years to win his freedom.

Seeing friends and family excited Angelos and filled him with gratitude for all the help he had received. "I feel blessed and lucky," he said.

Now Angelos, a former music producer, is starting life over, with no bitterness, as a different man.

"I've changed a lot," he said. "I'm not close to being the same person."

Angelos' plans include writing a book about his experience, making a documentary, becoming an advocate for criminal-justice reform and speaking to at-risk youths about avoiding the mistakes he made. He already has written a commentary about minimum-mandatory sentences for Time magazine.

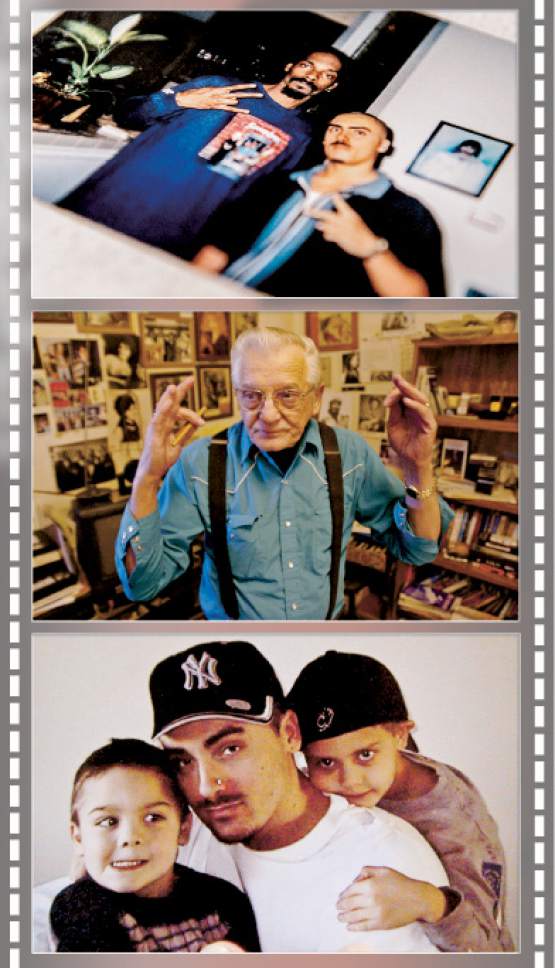

He has some job prospects and is assessing his choices, Angelos said. Before prison, he was running his Utah-based rap and hip-hop label, Extravagant Records, but is unsure if he wants to return to the music industry.

He recently listened to albums he produced before he was locked up and said, "It even sounds old school to me."

Whatever he ends up doing, Angelos said, he'll stay out of trouble and follow all the rules — what he calls "living in the square."

He's been inspired by close friend and former rapper Mutah "Napoleon" Beale, who was a member of 2pac Outlawz, a group founded by slain rapper Tupac Shakur. Beale, who left what he describes as an empty life in the music world, now gives talks to young people about the pitfalls of hip-hop culture.

Angelos said Beale, who is helping him get over his fear of public speaking, has shown him that change is possible. Beale is confident Angelos will succeed outside prison.

"Weldon has always been a man of principle and honor, someone who will make it against all odds," Beale wrote in an email. "His experience has opened his heart and mind in ways that we can least imagine. I believe he will do good for himself, his kids and troubled kids all around the globe, especially at home in America."

In the weeks since his release, Angelos' days have been filled with visits and calls from family, friends, filmmakers, journalists, lawyers, justice-reform advocates and others. Sometimes the activity so overwhelms Angelos that he has to step away to be by himself for a while. After so many years in prison, he's still getting used to life on the outside — and it's not easy.

At first, the bed in his sister and brother-in-law's guest bedroom at their Sandy home felt too soft, so he slept on the floor. But after prison meals, he's been delighting in Italian food and In-N-Out burgers. Angelos has secured a driver license — "Not having an ID for the first 10 days, I felt like I didn't exist," he said — and has gone on his first date in years.

He is trying to master his iPhone, a much different device than the flip phone he used pre-prison. He teases his sister Lisa Angelos, his most ardent supporter, that her job as his assistant is to handle his emails and phone calls. She laughingly reminds him that she quit that position.

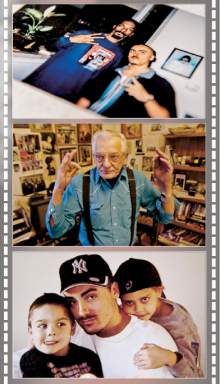

Angelos wants to save money so he can find a place for himself and his two sons, 17-year-old Jesse and 19-year-old Anthony, who have been living with his sister and her family for the past year. He also has a 13-year-old daughter, Meranda, who lives nearby with her mother.

Lisa Angelos, has set up a fundraiser on change.org, "Help my brother start his new life," with a $25,000 goal.

Her brother's return has made everyone happy, she said. "To see his kids smile on a regular basis is really wonderful."

Crime and punishment • The legal saga began in 2002, when Angelos sold small amounts of marijuana three times to a police informant. Each time, he charged $350 for eight ounces; at one transaction, he had a gun strapped to his ankle and a firearm in the vicinity at the other drug buys, prosecutors said. The then-22-year-old did not display a weapon at those sales.

A federal grand jury indicted Angelos on one gun possession count, three counts of marijuana distribution, one count of possession of a stolen firearm and one count of possession of a firearm with a removed serial number. Prosecutors offered Angelos a plea bargain that would have put him behind bars for 15 years.

A first offender, Angelos declined the deal. Calling the offer a "huge break," the U.S. attorney's office then obtained a new indictment with 20 counts that mandated a minimum 105-year sentence. Angelos later offered to plead guilty to one count each of drug distribution, possession of a firearm in furtherance of a drug trafficking crime and money laundering, which would have resulted in a shorter sentence than the 15 years he would have served under the plea bargain offered by prosecutors. The government declined his offer.

After a seven-day trial in U.S. District Court, a jury on Dec. 16, 2003, convicted Angelos of 16 counts of drug trafficking, weapons possession and money laundering. One charge was dismissed, and the jury acquitted him on three other counts.

Federal law required a sentence of at least 55 years without parole for the three convictions of possessing a firearm during a drug-trafficking crime. Angelos, who had been free during the trial, was immediately taken into custody.

Sentencing came almost a year later, on Nov. 16, 2004, after the issue of whether the 55-year mandatory sentence was constitutional had been thoroughly briefed. In a lengthy ruling, then-Judge Paul Cassell reluctantly imposed what he called an "unjust and cruel and even irrational" punishment and recommended that President George W. Bush commute the sentence to a shorter prison term.

There is no parole in the federal system, which means offenders serve their entire sentences, minus any "good time" credit they earn for their behavior in prison. Angelos' estimated release date had been Nov. 18, 2051, when he would be 72.

After the sentencing, Assistant U.S. Attorney Robert Lund, who prosecuted the case, said the term would send the message to armed drug dealers that they face serious consequences. He also said there was "no chance at all" the president would reduce Angelos' sentence.

Doing time • Because there are no federal prisons in Utah, Angelos served his sentence in California. He began his stretch behind bars at the Federal Correctional Institution in Lompoc in Santa Barbara County, then was moved in 2014 to FCI Mendota in Fresno County.

Instead of simply biding his time, Angelos put his energy into improving himself.

"I've been preparing to come home since I got there," he said. "I just buried myself in books."

A high school dropout, he earned a business certificate from the California-based Coastline Community College and 80 college credits, Angelos said, adding that he would like to get a bachelor's degree.

Angelos also worked in the prison dental lab and as a computer tutor. He got into trouble while incarcerated only once, he said, when he used someone else's cellphone to make a call.

Angelos had only a few visits from family members because of the expense of traveling to California. The last time he saw his father was during a 2007 visit; James Angelos died Jan. 4, 2015, without seeing his son reunited with the family.

Although Angelos believed he would get out before serving his full term, he went through ups and downs. Particularly tough were the days when presidential commutations and pardons were announced and, time after time, his name wasn't on the list.

Lund's assertion that the president would never reduce his sentence kept running through his mind, Angelos said. But he also thought about Cassell's strongly worded statement about the unfairness of his punishment.

"It's what gave me hope something would happen."

Asking for mercy • The government insisted the punishment was appropriate because Angelos allegedly had gang affiliations and frequently carried weapons. Angelos acknowledged he ran with a rough crowd while growing up in the Salt Lake Valley, but wasn't in a gang.

The prison term sparked a national furor over mandatory sentences and prompted dozens of former judges and prosecutors to join in court briefs seeking to reverse the punishment.

But U.S. District Judge Tena Campbell denied a motion for resentencing, rejecting a claim that Angelos' trial attorney had mishandled plea negotiations. The 10th Circuit Court of Appeals rejected Angelos' appeal, and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear his case.

The effort then turned to winning presidential clemency. More than 100 politicians, activists, scholars, corrections officials, former judges, former prosecutors and others signed a letter supporting clemency. Cassell, who stepped down from the bench in 2007 and is now a University of Utah law professor, wrote his own letter urging commutation.

The campaign went online, with more than 250,000 people joining a petition calling for Angelos' release. Documentaries on the case included "The Story of Weldon Angelos," by the nonpartisan advocacy organization Generation Opportunity, and "Blind Justice: The Case of Weldon Angelos" by former Utahn Valerie Douroux Schultz.

Lisa Angelos worked tirelessly to keep her brother's story in the public eye and garner support for his release.

"She never lost her resolve," said former Salt Lake City Mayor Rocky Anderson, one of the lawyers who joined the effort. "She never gave up on Weldon."

The sentence was never commuted, but Angelos unexpectedly was released May 31 after receiving an immediate sentence reduction. The records of how all this came about are sealed, but Angelos' lawyer, Mark Osler, a law professor at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota, told The Washington Post his client is free "because of the fair and good action of a prosecutor."

Attorney Erik Luna, who was part of the legal team handling Angelos' appeal, believes the "clarion call" for a commutation helped.

"I suspect that the sheer level of public support for his clemency bid and the gravitas of the signatories to the clemency letter played some part in his eventual release," said Luna, a former University of Utah law professor who now teaches at Arizona State University.

Advocates are pleased Angelos is free but continue to fight for comprehensive criminal-justice reform.

Mark Holden, general counsel and senior vice president at Koch Industries in Kansas, said many prisoners are serving long mandatory sentences for nonviolent crimes. The principal owners of Koch Industries, brothers Charles and David Koch, have been pushing for reform for years.

"The whole system needs to be fixed across the board," Holden said.

Celebrating freedom • At the June 18 party celebrating Angelos' return, Schultz, who made the "Blind Justice" documentary, marveled at the turn of events.

Schultz was a U. student and president of the school's Students for Sensible Drug Policy chapter when she heard about Angelos' case and decided to tell his story.

She interviewed Angelos at the Davis County Jail in 2009, when he was brought back to Utah for a hearing on his appeal. Seven years later, she said, it felt surreal to be talking to him in his sister's backyard.

"Weldon's release came out of nowhere," said Schultz, who is now the creative director of Los Angeles-based Concise Focus.

"Who can imagine that 13 years later you would be here now?" she asked Angelos, as the group toasted his future.

Landon Stokoe, a longtime friend, said Angelos is driven and will do well.

"His story inspires hope," Stokoe added. "He had the worst case of all — 55 years."

Noting the presence at the party of four attorneys who helped on the case — Anderson, Luna, Holden and Troy Booher, a Salt Lake City lawyer — Stokoe said, "They're just good people. It's amazing when you get people to come together for a common goal."

With that circle of support and his own determination, Angelos expects to be "living in the square" for the rest of his days.

Twitter: @PamelaMansonSLC