This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Provo • Most forensic evidence from recent sexual assaults in Utah remains unexamined despite public pressure for more timely testing, according to new research from Brigham Young University.

Utah police departments forward the evidence to crime labs at about one-third the rate of other areas across the country. And the odds of a DNA analysis are less likely for assaults reported in Utah's rural southwestern corner, found the study released Thursday.

"It means justice denied," said Julie Valentine, principal investigator and a BYU nursing professor, "for those victims that had sexual assault kits that were collected but never submitted."

About 60 percent of the swabs and other samples taken from 2010 to 2013 and included in the study — or 1,160 "rape kits" — still were waiting in labs as of Dec. 31, 2015, the report found. About 22 percent had been tested within a year, compared to about 60 percent in Michigan and San Diego, as reported in similar studies. The local analysis did not consider each case in Utah. It traced 1,870 kits collected from people who signed a form to say they wanted the case to go to law enforcement.

And location in part determined how far evidence could go. Washington County referred about 20 percent of its kits to the lab, while Salt Lake and Iron counties sent about 40 percent — a slight 4 percent increase over the northern counties of Weber, Davis, Morgan and Box Elder.

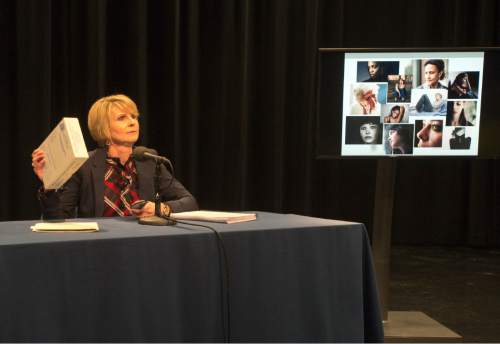

"I was blown away," Valentine said, "by the differences between the sites." She believes her analysis paints the most detailed picture to date of how sexual assault evidence is processed — or isn't — in Utah. The forensic nurse released the findings at a news conference Thursday at BYU.

Her study comes two years after state and local officials vowed to speed up the process. Lawmakers have slotted about $3 million to pay for testing at private labs to ease the backlog, and the state also received national grants.

The progress is slow but meaningful. A private lab hired by the state has finished testing at least 400 of the samples, said Jay Henry, director of the Utah Bureau of Forensic Services. The genetic information has generated 51 leads on possible suspects, he said.

Henry expects each of 2,700 kits piled up in his lab to be tested by summer 2017. He believes a handful of grants and a $750,000 boost from the Legislature will allow his employees to test each kit statewide, so he is asking law enforcement to send each of the cardboard containers that is smaller than a shoebox.

Before the grants, he said, his lab "conditioned" law enforcement to send only limited samples of blood, semen or other materials because it did not have the money or manpower to review each one.

"Now we do" have the resources, Henry said, "so we're changing our tune a little bit."

Before the 2015 shift, police in Washington County generally forwarded kits only if officers still were searching for a suspect or if an alleged assailant denied that any sexual activity took place.

"I don't think we should draw the conclusion that cases were being neglected," said Washington County Attorney Brock Belnap. Rather, he said, police understood the constraints on the state lab.

St. George police had a similar protocol. The county and the city have begun passing all cases onward, they said in statements.

Samples usually are collected at a hospital about a day after an assault is reported to police, Valentine found. It can take months for labs to process them and send back results.

Weber County sheriff's Lt. Lane Findlay says a 2014 state grant helped his office whittle down to nine 30 nonsubmitted kits collected since 1999.

"We still have some work to do," Findlay said. "It's something that we're working on."

But it isn't enough for Utah to encourage its officers to move the cases forward, said Valentine. She wants mandatory testing written into the state code, though no lawmaker appears ready to sponsor a bill.

"It's a public safety issue," Valentine said, adding a comprehensive DNA database could identify offenders who attack multiple victims.

Valentine on Thursday urged police to treat each kit the same and to understand that trauma sometimes prevents victims from remembering assaults in their entirety.

She has worked with West Valley City police on both issues over the past two years. In that time, Chief Lee Russo said, sexual assault prosecution rates have risen from single into double digits. He declined to give specifics.

His department is one of many across the country now grappling with a backlog of evidence and few resources. Oregon, for example, has sent thousands of kits to private labs in Utah for testing, while Utah is contracting with a company in Virginia.

Only about 12 percent of victims, Valentine said, report rape to police.

"I'm sharing with you the tip of the iceberg," she said.

Twitter: @jm_miller; @anniebknox -

Processing the backlog

The analysis showed 12 percent of rape kits went to the state lab within a month, 10 percent went within a year, 15 percent took longer than a year to be submitted and 61 percent still haven't been processed.

The study indicates that Utah police agencies favor processing evidence from men who come forward as sexual assault victims: They were 46 percent more likely to forward kits collected from men.

The odds also increased 25 percent when police suspected a victim was drugged. But the likelihood dropped if a victim was using drugs beforehand, had showered before the forensic examination, was physically or mentally impaired due to illness, or knew the suspect.