This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Draper • The Catholic pope has a telescope with a mirror that was made by an angel in a synagogue.

If it sounds like the punch line from a joke, it's not.

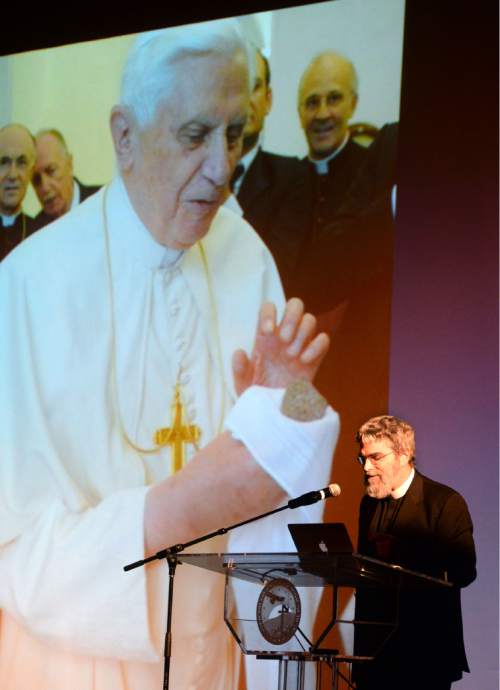

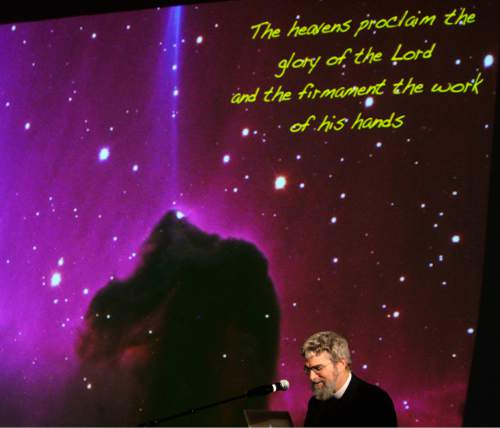

It's just part of the way Jesuit Brother Guy Consolmagno, director of the Vatican Observatory, weaves humor into the conversation about the relationship — some would say split — between science and faith.

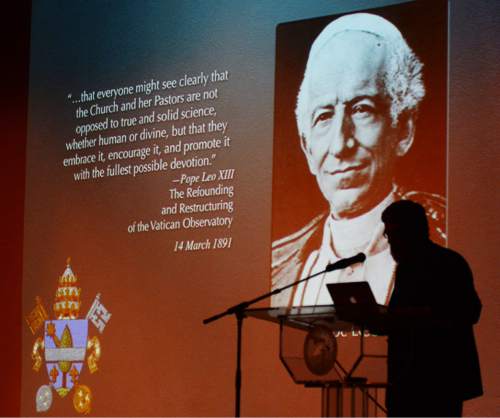

It's a conversation, he said Sunday in a speech at Juan Diego Catholic High School, that's been going on inside the Roman Catholic Church since the 1580s, when then-Pope Gregory XIII committed the church to scientific study as part of the reform of the Julian calendar.

"Pope Leo wanted an observatory so that everyone might see the church is not opposed to solid science," Consolmagno said, "but embraces it and encourages it with full devotion."

The first telescopes went up on Vatican walls. In the 1930s, when light pollution muddied the dark skies above Rome, the Vatican Observatory was moved to the papal summer residence at Castel Gandolfo, in Italy, where scientists lived and worked in rooms above the pope's own apartments, he said, setting the audience up for another joke.

"We were the only people in the entire Vatican, in the entire Catholic Church who were above the pope," he said.

Despite his jokes and deadpan delivery, Consolmagno is a serious scientist with degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of Arizona. He taught physics and astronomy in the Peace Corps and was a post-doctorate lecturer at MIT and Harvard College before entering the Jesuit order in 1989.

His research on asteroids, meteorites and the evolution of small bodies in the solar system has earned him a Carl Sagan Medal from the American Astronomical Society and, in 2000, a 12-mile-wide asteroid that orbits the sun named after him — "4597 Consolmagno."

Consolmagno was in Utah this week to give lectures at Utah Valley University and Brigham Young University. He was invited to speak at Juan Diego by Juliana Boerio-Goates, an emeritus professor of chemistry from BYU, who was in a Consolmagno-led workshop on faith and astronomy last year.

Consolmagno, she said, brings an important message for young students that science and faith don't have to be seen as incompatible or irreconcilable.

"To me (the issue) comes down to two problems: Scientists not having enough humility to understand, that they don't have all the answers and religion not having enough to recognize that they can't tell God how he should have made the universe," she said.

A Detroit native who fell in love with the stars in his youth, Consolmagno said science and faith have jointly provided him with adventure and opportunity around the world. From the best universities in the United States, to Italy, Hawaii, Antarctica — where he dug fragments of meteorites out of the frozen tundra — to Arizona.

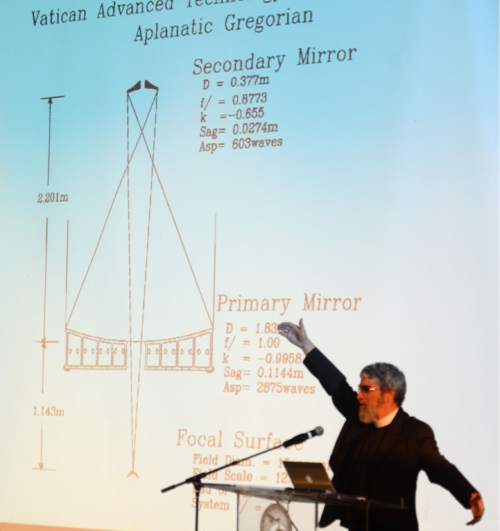

That's where the Vatican has a Tucson research center and a short-focal-length telescope inside the University of Arizona's Mount Graham International Observatory near Safford, Ariz. The telescope was built through a university-Vatican partnership in the 1980s with technology developed by astronomer Roger Angel, who used an abandoned synagogue as his research laboratory.

Nothing in Consolmagno's work, nor in the Vatican's commitment to science, is done with an eye toward proving the definitive existence of God or even creationism.

Rather, he said in an observatory video clip played during the presentation, science and religion are both conversations about the universe, how it works and the ways in which we humans interact with it.

"Religion gives me the reason to do the science," he said.

Juan Diego juniors Serena Hawatmeh and Alannah Clay said they loved Consolmagno's message and were encouraged by the news that their faith values science.

"I really liked that the reason he wanted to study the universe was so that he could get closer to the Creator," said Hawatmeh.

Both girls said they are looking toward careers in medicine, and Clay said that, as an active Catholic, she is comforted knowing she can easily continue to serve the church without conflict.

"It was just cool," she said, "to hear that science and religion can work together."