Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam's volunteer Emad Sarraj tapes newly packed gift boxes closed

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

l-r Hassan Abdul, sister Farida, mother Hasena Osman, and sister Sofiya, refugees from Burm

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Hassan Abdul and his mother Hasena Osman, refugees from Burma, smile as Jefferey Griffith (

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

l-r Hassan Abdul smiles as his sister Sofiya Abdul is handed a basket of clothes The family

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Volunteer Ulrike Dannhauer wheels out a pallet of good headed to a senior center December 2

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Sudanese refugee Yacoub Arbab, 24, smiles as Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam volunteer Lois

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Refugee families receive blankets, clothing, coats, hygiene kits, detergent, rice, oil, spi

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Sudanese refugee Yacoub Arbab, 24, and his brother Hisseine Arbab smiles as Shalom, Salaam

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam's co-chair Scott Klepper organizes the group of people who w

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

The front door of one of the refugee families receiving gifts from Shalom, Salaam – Tikku

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Burmese refugees Farida Abdul, left, brother Hassan Abdul, mother Hasena Osman holding daug

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Sudanese refugee Mohamed Arbab, 5, is all smiles after he was helped into his new fleece sh

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Sudanese refugee Fatime Yaya smiles as Shalom, Salaam ñ Tikkun Olam volunteer Lois Speige

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam's volunteer Emad Sarraj tapes newly packed gift boxes closed for delivery. Refugee families receive blankets, clothing, coats, hygiene kits, detergent, rice, oil, spices, potatoes, fruit, vegetables and bread on Christmas day. No Christmas themed items are included, yet the items are representative of as unity and celebration of all refugees. Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam Christmas Day Project, a project that reaches hundreds in need, including 100 refugee families and 350 seniors, as well as residents of area shelters. The charity includes more than 300 volunteers from diverse religious, cultural, and educational backgrounds who prepare and deliver packages made up of food, household goods, gifts, and gift cards, all of which are donated by participating retailers or purchased with donated funds.

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

l-r Hassan Abdul, sister Farida, mother Hasena Osman, and sister Sofiya, refugees from Burma, receive gifts on Christmas day, December 25, 2015 to their home. Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam Christmas Day Project, is a project that reaches hundreds in need, including 100 refugee families and 350 seniors, as well as residents of area shelters. The charity includes more than 300 volunteers from diverse religious, cultural, and educational backgrounds who prepare and deliver packages made up of food, household goods, gifts, and gift cards, all of which are donated by participating retailers or purchased with donated funds.

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Hassan Abdul and his mother Hasena Osman, refugees from Burma, smile as Jefferey Griffith (center), his mother Mary Griffith and his brothers deliver gifts on Christmas day, December 25, 2015 to their home. Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam Christmas Day Project, is a project that reaches hundreds in need, including 100 refugee families and 350 seniors, as well as residents of area shelters. The charity includes more than 300 volunteers from diverse religious, cultural, and educational backgrounds who prepare and deliver packages made up of food, household goods, gifts, and gift cards, all of which are donated by participating retailers or purchased with donated funds.

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

l-r Hassan Abdul smiles as his sister Sofiya Abdul is handed a basket of clothes The family of refugees are from Burma. Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam Christmas Day Project, is a project that reaches hundreds in need, including 100 refugee families and 350 seniors, as well as residents of area shelters. The charity includes more than 300 volunteers from diverse religious, cultural, and educational backgrounds who prepare and deliver packages made up of food, household goods, gifts, and gift cards, all of which are donated by participating retailers or purchased with donated funds.

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Volunteer Ulrike Dannhauer wheels out a pallet of good headed to a senior center December 25, 2015. Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam Christmas Day Project, a project that reaches hundreds in need, including 100 refugee families and 350 seniors, as well as residents of area shelters. The charity includes more than 300 volunteers from diverse religious, cultural, and educational backgrounds who prepare and deliver packages made up of food, household goods, gifts, and gift cards, all of which are donated by participating retailers or purchased with donated funds.

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Sudanese refugee Yacoub Arbab, 24, smiles as Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam volunteer Lois Speigel hands him gifts for his family of four at his home, December 25, 2015. Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam Christmas Day Project, a project that reaches hundreds in need, including 100 refugee families and 350 seniors, as well as residents of area shelters. The charity includes more than 300 volunteers from diverse religious, cultural, and educational backgrounds who prepare and deliver packages made up of food, household goods, gifts, and gift cards, all of which are donated by participating retailers or purchased with donated funds.

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Refugee families receive blankets, clothing, coats, hygiene kits, detergent, rice, oil, spices, potatoes, fruit, vegetables and bread on Christmas day. No Christmas themed items are included, yet the items are representative of as unity and celebration of all refugees.

December 25, 2015. Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam Christmas Day Project, a project that reaches hundreds in need, including 100 refugee families and 350 seniors, as well as residents of area shelters. The charity includes more than 300 volunteers from diverse religious, cultural, and educational backgrounds who prepare and deliver packages made up of food, household goods, gifts, and gift cards, all of which are donated by participating retailers or purchased with donated funds.

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Sudanese refugee Yacoub Arbab, 24, and his brother Hisseine Arbab smiles as Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam volunteer Bert Speigel shake hands and pleasantries after delivering gifts to their family, December 25, 2015. Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam Christmas Day Project, a project that reaches hundreds in need, including 100 refugee families and 350 seniors, as well as residents of area shelters. The charity includes more than 300 volunteers from diverse religious, cultural, and educational backgrounds who prepare and deliver packages made up of food, household goods, gifts, and gift cards, all of which are donated by participating retailers or purchased with donated funds.

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam's co-chair Scott Klepper organizes the group of people who will deliver gifts to the refugees. Refugee families receive blankets, clothing, coats, hygiene kits, detergent, rice, oil, spices, potatoes, fruit, vegetables and bread on Christmas day. No Christmas themed items are included, yet the items are representative of as unity and celebration of all refugees. Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam Christmas Day Project, a project that reaches hundreds in need, including 100 refugee families and 350 seniors, as well as residents of area shelters. The charity includes more than 300 volunteers from diverse religious, cultural, and educational backgrounds who prepare and deliver packages made up of food, household goods, gifts, and gift cards, all of which are donated by participating retailers or purchased with donated funds.

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

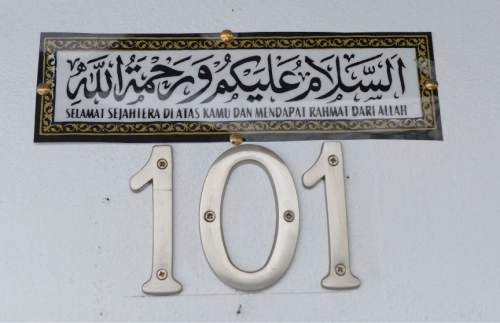

The front door of one of the refugee families receiving gifts from Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam ,

December 25, 2015. Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam Christmas Day Project, is a project that reaches hundreds in need, including 100 refugee families and 350 seniors, as well as residents of area shelters. The charity includes more than 300 volunteers from diverse religious, cultural, and educational backgrounds who prepare and deliver packages made up of food, household goods, gifts, and gift cards, all of which are donated by participating retailers or purchased with donated funds.

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Burmese refugees Farida Abdul, left, brother Hassan Abdul, mother Hasena Osman holding daughter Natasha, receive gifts on Christmas day, December 25, 2015 to their home. Shalom, Salaam ñ Tikkun Olam Christmas Day Project, is a project that reaches hundreds in need, including 100 refugee families and 350 seniors, as well as residents of area shelters. The charity includes more than 300 volunteers from diverse religious, cultural, and educational backgrounds who prepare and deliver packages made up of food, household goods, gifts, and gift cards, all of which are donated by participating retailers or purchased with donated funds.

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Sudanese refugee Mohamed Arbab, 5, is all smiles after he was helped into his new fleece shirt by his mother Fatime Yaya, December 25, 2015. Shalom, Salaam – Tikkun Olam Christmas Day Project, a project that reaches hundreds in need, including 100 refugee families and 350 seniors, as well as residents of area shelters. The charity includes more than 300 volunteers from diverse religious, cultural, and educational backgrounds who prepare and deliver packages made up of food, household goods, gifts, and gift cards, all of which are donated by participating retailers or purchased with donated funds.

Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune

Sudanese refugee Fatime Yaya smiles as Shalom, Salaam ñ Tikkun Olam volunteer Lois Speigel hands her gifts for her family of four at her home on Friday. Shalom, Salaam ñ Tikkun Olam Christmas Day Project, a project that reaches hundreds in need, including 100 refugee families and 350 seniors, as well as residents of area shelters. The charity includes more than 300 volunteers from diverse religious, cultural, and educational backgrounds who prepare and deliver packages made up of food, household goods, gifts, and gift cards, all of which are donated by participating retailers or purchased with donated funds.