This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

With hours left to live, Joe Hill was relaxed and ready for his final interview.

No hard feelings, he told a small group of Utah reporters allowed into the state prison on Nov. 18, 1915, though he did feel he had been "the victim of an unfair trial and injustice."

And no regrets. "I can sincerely say that never in my life have I done anything for which I should now be sorry."

Would Hill, a renowned songwriter for the Industrial Workers of the World, finally explain how he was shot on the same night that John and Arling Morrison were murdered?

"It is only public curiosity that wants to know that. I am not here to satisfy public curiosity."

In answer to his own question — "What do I expect to accomplish by my situation?" — Hill quipped, "Well, it won't do the IWW any harm and it won't do the state of Utah any good."

Some of what Hill said that night was strictly personal. He asked for grape juice with his last meal, and wrote to Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, the famous IWW orator and muse for his song "Rebel Girl," to say he had given a photo of her son Buster to his friend Hilda Erickson.

But most of Hill's final words were in line with the symbol he had become.

In another letter to Gurley Flynn, Hill said, "I have lived like a rebel and I die like a rebel."

Hill sent a telegram to IWW leader William Haywood, instructing: "Don't waste any time mourning — organize!"

He ended the missive with the famous request that his body be taken to the state line.

"I don't want to be found dead in Utah."

At around 10 p.m., Hill handed a prison guard a piece of paper with "My Last Will" written at the top in pencil.

Decades later, biographer Gibbs Smith described it as "prized piece of poetry in the heritage of the American labor movement."

Hill starts with the couplet, "My will is easy to decide for there is nothing to divide." He describes his desire to be cremated and scattered on the "merry breezes," so that his ashes would help the flowers "come to life and bloom again."

"Good luck to all of you," the poem ends.

But Hill's calm had broken when he woke up around 5 a.m. He barricaded his cell with his mattress and wrapped torn strips of his blanket through the bars to block the door from opening. Grabbing a broom that had been left in his cell, he broke the handle and stabbed at guards with the jagged end.

When Sheriff John Corless arrived and chastised him, Hill capitulated. "Well, I'm through," he said, "but you can't blame a man for fighting for his life."

After 7 a.m., Corless led Hill to the prison yard, where Hill, blindfolded, was seated in a chair facing the blacksmith shop. The firing squad was inside, concealed behind a canvas drape.

A doctor pinned a paper target over Hill's heart.

After declaring that his conscience was clear, Hill called out to his friends, "I am going now, boys. Goodbye!"

There was no response.

Local IWW leader Ed Rowan, one of Hill's chosen witnesses, and other supporters had been refused entry by the prison warden.

The sun rose as the friends waited outside, and they began to be hopeful. Perhaps Utah Gov. William Spry had given in to President Woodrow Wilson's second request for a stay of execution.

Inside the prison, Hill called out again, "Goodbye, boys!"

Newspapers gave conflicting reports of Hill's last words. But all agreed that as the deputy began, "Ready, aim ..." Hill interrupted: "Fire!", summoning the bullets into his own heart. —

Online: Explore 'The Legacy of Joe Hill'

Who was Joe Hill? Why does he inspire musicians and social justice activists today?

To mark the centennial of Hill's execution, The Salt Lake Tribune created JoeHill.sltrib.com. Visit the site to find historic photos and original documents about Hill's trial and execution. Meet the family who has been grieving John and Arling Morrison for a century. Learn about Hill's musical legacy, and listen to Utah artists performing his trademark songs. › JoeHill.sltrib.com.

![Jeremy Harmon | The Salt Lake Tribune

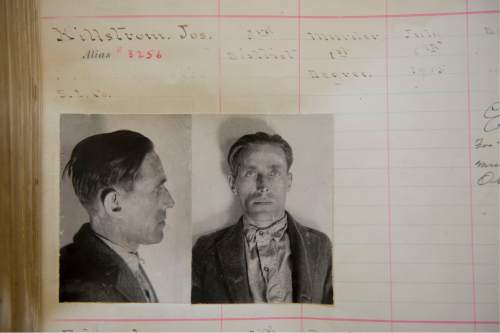

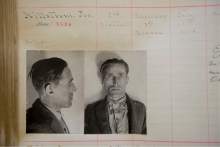

This handwritten description of Joe Hill's execution is part of his prison record at the Utah State Prison. (The first names of John and Arling Morrison are incorrect.) It says:

Executed Nov 19th 1915 at 7:22 am - Shot

for the murder of Jack [sic] Morrison store keeper

murder in connection with hold up.

Orlin [sic] Morrison was killed by gun shot

Photo courtesy Utah State Prison](https://archive.sltrib.com/images/2015/1119/Hilltimeline_111915~2.jpg)

![Jeremy Harmon | The Salt Lake Tribune

This handwritten description of Joe Hill's execution is part of his prison record at the Utah State Prison. (The first names of John and Arling Morrison are incorrect.) It says:

Executed Nov 19th 1915 at 7:22 am - Shot

for the murder of Jack [sic] Morrison store keeper

murder in connection with hold up.

Orlin [sic] Morrison was killed by gun shot

Photo courtesy Utah State Prison](https://archive.sltrib.com/images/2015/1118/Hilltimeline_111915~2.jpg)