This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

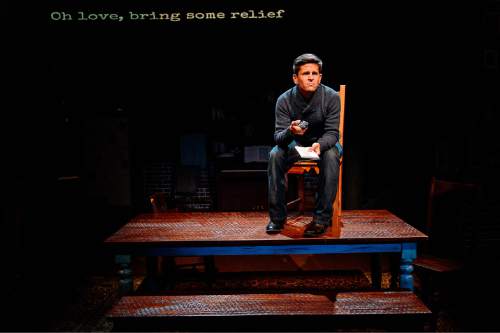

To understand the intricacies of "Tribes," British playwright Nina Raine's layered drama about dysfunctional British family members who come to understand they haven't been listening to their deaf son, Billy, consider the complications of casting.

For the work's regional premiere, Salt Lake Acting Company originally cast a 20-something, smart, agile Utah-trained actor, Austin Archer, who had moved to New York City after earning his Actors' Equity card last season at Pioneer Theatre Company.

But after the local deaf community threw up some red flags, the company reconsidered. Archer was asked to assist director Andra Harbold; Stephen Drabicki, a New York-based actor who is deaf, was cast to play Billy. (He explains he is Deaf, the label for those who are culturally deaf, that is, identify with the deaf community and use sign language, while small-d deaf designates those who are medically deaf but don't identify with the culture. Journalism style is less particular — The Salt Lake Tribune uses deaf inclusively.)

The Salt Lake City run marks the Kentucky-raised actor's fifth time playing Billy, after productions in Canada, Sacramento and Portland, Ore. He is one of a tribe of 20-something d/Deaf actors who find themselves traveling the country to perform the role after its London premiere in 2010. The play won the 2012 Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Play for its off-Broadway New York City run and has become a popular selection for regional theaters such as the Salt Lake Acting Company.

Drabicki says he relishes the chance to work and doesn't worry about being typecast in the role, while he acknowledges that the popularity of the play has produced something of a casting double bind.

"Tribes," which is aimed at audiences who can hear, explicates some of the complexities of being deaf, but it also has caused hearing actors to be cast in the role. "Simply wrong," Drabicki explains in an email interview. "Cultural, language and deaf or disability appropriation shouldn't be something we see this often in American theaters."

Some advocates describe it as a civil-rights issue, similar to white actors performing in yellow face or black face. Yet that's a sensitive philosophical conundrum in the acting community, where craft often helps actors of all sizes and colors play across type, age and disability. One example was Pygmalion Productions' successful run of "Mockingbird" last year, when a nonautistic young actor played the title character.

"There aren't many opportunities for deaf actors out there," says actor Teresa Sanderson, who serves as an informal spokeswoman to the local deaf community through her in-laws, who are deaf and taught her to sign. Although she was critically lauded recently for her sensitivity in playing a transgender character, she says she would never choose to play a deaf role, because signing is not her native language. "Why wouldn't you, if you could, use somebody who knows what that means?"

Amid those concerns, SLAC hired American Sign Language specialists Britton Auman and Carol MacNicholl and interpreters Maggie Smith and Emily Longshore. The company plans to offer two signed performances for deaf audience members.

How Cynthia Fleming, the company's artistic director, refers to the production's backstory: "Our deaf community has really taught us a lot."

"Really, any time you think the line is unclear on who gets to play what, you need to ask the community," is how Archer, the assistant director, describes casting issues.

SLAC's casting shuffle is most interesting as it underscores the themes of Raine's play, which are set into motion after Billy comes to learn sign language from his new girlfriend, Sylvia, the daughter of deaf parents who is losing her hearing. By learning to communicate with Sylvia and, through her, the deaf community, Billy comes to understand that his family's insistence on him not learning sign language has muted his voice.

His sister and brother, who can hear, also have been stunted by their father's critical, biting communication style. (Paul Kiernan plays Christopher, the father, and Sarah Shippobotham plays the mother, Beth.) "The play is so English," says Harbold, the director, who earned her master's degree at the University of London Goldsmiths College, and explains a crude sort of repartee in British theater that plays as witty, not devastating. "The language from an American mouth would be so monstrous and odious, but it's British."

What sets apart the play is how each character is forced to confront the question of how you can actually express yourself — and your love — in words.

The playwright's choice of "Tribes" as a title "evokes an ancient and primal sense of territory and beliefs: whom you belong to, who protects you from 'them' and who and what belongs to you," Harbold says. "Add to that a modern, idiosyncratic family who pride themselves on not falling into step with the common horde. 'Tribes' wrestles with huge questions of communication, identity and empathy in such a personal way — it can be at once intensely funny and intensely painful."

As Billy learns a new language, the course of his romance with Sylvia changes his relationship with his family, particularly his ties to his narcissistic older brother, Daniel (Matthew Sincell). The brothers' relationship carries the core of the play's questions, the director says. Harbold terms Billy the play's catalyst, while Sylvia (played by Amy Ware) serves as a bridge between the hearing and the deaf, the two worlds of the play. "She changes the dynamics of the family," Harbold says, "and I think both brothers fall in love with her."

In an email interview, Drabicki says he has moderate/severe bilateral sensorineural hearing loss and grew up in North Carolina using hearing aids and lip reading to negotiate the hearing world. He was home-schooled until college, when he finally learned sign language. His experience gives him a deep empathy for the character of Billy.

Drabicki's presence has changed the play's staging technically, Harbold says, as in rehearsals she has come to realize how often characters in contemporary theater are blocked to cheat — for example, they are likely to face the audience and speak, instead of directly facing each other. "I've been trying to watch the play imagining I'm deaf," she says. "If someone turns upstage, I lose that part of the story."

Also interesting is the fact that the character's spoken dialogue remains as designated in the script, but signs have been translated figuratively and differently in each production, which speaks to the fluid nature of sign language.

"Having Stephen in the room makes the show so much stronger," says Archer, praising his colleague's strength as an actor, as well as his patience with hearing colleagues who don't always remember that he needs to see their lips. "It has forced us all to confront the reality of the play."

facebook.com/ellen.weist —

Learning to listen

Salt Lake Acting Company presents British playwright Nina Raine's family drama "Tribes."

When • Oct. 21-Nov. 15; Wednesday-Saturday, 7:30 p.m.; Sunday, 1 and 6 p.m.

Additional performances • Tuesdays, Nov. 3 and 10, 7:30 p.m.; and Saturdays, Nov. 7 and 14, 2 p.m.

Where • SLAC, 168 W. 500 North, Salt Lake City

Tickets • $15-$42 (depending on performance), with student, senior, group and 30-and-under discounts, at 801-363-7522 or saltlakeactingcompany.org