This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

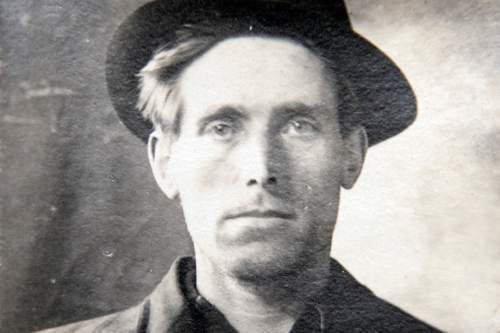

A criminal defense attorney is asking Utah to pardon Joe Hill, a labor union martyr and songwriter whose execution for murder nearly 100 years ago still provokes passionate arguments about whether a firing squad shot an innocent man.

Attorney Clayton Simms of Salt Lake City filed the request with the Utah Board of Pardons and Parole this week, just before Labor Day weekend activities will mark the centennial of Hill's execution, an act for which Utah remains infamous to some.

Learn more about Joe Hill and the controversy at The Tribune website, The Legacy of Joe Hill.

Hill was executed for the murder of grocer John G. Morrison, who was shot to death, along with his teenage son, on Jan. 10, 1914.

"History has demonstrated that Joe Hill is innocent," Simms wrote in the application for a pardon. "It is respectfully requested that his murder conviction be vacated and that Joe Hill should be pardoned for a crime he did not commit."

Morrison's descendants are adamant that Hill was one of the two gunmen and that his execution was justified, though some family members acknowledge there's room for doubt.

Jay Arling Morrison of Highland, a great-grandson, said the petition left him not knowing "whether to laugh or be annoyed." While he didn't want to argue Hill's guilt or innocence, Morrison said he did want to point out "that we can't establish facts about the case 100 years later."

Simms said he based his conclusion on Hill's innocence in part on assertions by Colorado author William M. Adler in a recent book titled "The Man Who Never Died." It reexamines the events surrounding the murders, which occurred on the same night Hill showed up at a doctor's office with a bullet wound. Prosecutors claimed he was shot by 17-year-old Arling Morrison.

Adler cited a 1949 letter that he turned up from Hill acquaintance Hilda Erickson, who wrote that Hill told her in 1914 that he had been shot by their friend Otto Appelquist. Erickson had recently broken off an engagement to Appelquist, and he and Hill may have quarreled over Hill's involvement with Erickson.

Adler also pointed to a lifelong, violent criminal as a likely suspect instead of Hill.

Hill told a doctor on the night of the murders that he had been shot in a quarrel over a woman but he never revealed — even when facing execution — the name of the woman involved, who shot him or the location of the incident.

"I think it's likely that he was innocent and he chose not to bring out that alibi because he didn't want to embarrass or bring shame on this woman," Simms said Friday.

Hill's case went before the Utah Board of Pardons in 1915 and it met numerous times to consider his appeal. Its members consisted of the governor, the attorney general and three justices of the Utah Supreme Court, which by then already had upheld Hill's conviction.

The board seemed eager to consider commuting Hill's death sentence to life in prison, giving him a number of opportunities to provide details of his alibi. But Hill steadfastly declined to do so and even quit attending board sessions where his case was being considered.

Instead, Hill clung to the assertion that he was innocent and that he deserved a new trial.

Simms admits there's a question about whether someone can be pardoned after execution.

The Utah Attorney General's Office declined comment on Friday.

Simms' effort is not the first time the question of a pardon has been raised since the Nov. 19, 2015, execution.

In 1977, a state legislator, Sen. Ernest Dean, D-American Fork, introduced a resolution asking the Board of Pardons to review Hill's case, according to newspaper accounts. The resolution apparently went nowhere.

Dean was prompted in part by a letter-writing campaign by Swedish immigrant Folke Geary Anderson of Oakland, Calif., who pestered Utah officials to act on a pardon.

In 1979, AFL-CIO President George Meany asked Gov. Scott Matheson to grant a posthumous pardon to Hill as "a worthy expression of the humane impulses of the government and people of Utah," according to news accounts. Hill was a member of the Industrial Workers of the World.

Union activists also launched a petition drive that year seeking a pardon. The Swedish Communist Party demanded Utah "reverse the unfair and cruel ruling that was given against our outstanding labor organizer and songwriter."

Matheson referred the pardon requests to the Attorney General's Office, which issued an opinion saying neither the Utah Constitution, nor state, federal or English common law provided for a pardon after an execution.