This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Utah's national parks aren't failing the dirty air test — but just barely.

In a new assessment, a report card for polluted parks from the National Parks Conservation Association, three of the state's "Mighty Five" got D grades for two out of three clean-air categories. And another two earned just middling C's.

Out of 48 national parks ranked by grade, Zion came in 16th — the state's worst. Next-polluted was Capitol Reef at No. 21, followed by Bryce at No. 22. Canyonlands and Arches — both with straight C grades — were No. 29 and 30.

Using air quality data spanning from 2008 to 2013, the nonprofit's science staff generated thresholds for grade levels in three categories: ozone, visibility and changing climate.

"We were trying to make it accessible to people and trying to capture a sense of how air pollution is impacting the parks in these three different areas," said Nathan Miller, engineering and science manager for NPCA's clean-air program.

The grades are based on the number of days of unhealthy air quality, the average miles of visibility lost to pollution-related haze and the frequency of weather that deviates from each park's known historical norms.

"It's a good representation of the data that is out there," Miller said.

Sequoia National Park and Kings Canyon National Park, both located in California, tied for the worst pollution, according to the report. Both parks scored an F for healthy air, a D for visibility and a D for climate change.

None of the Utah park managers contacted about the air-quality report card would comment.

NPCA is an independent organization that advocates for the national parks, which are managed under the U.S. Department of the Interior. The association has used the Clean Air Act's 1999 Regional Haze Rule to prod states to develop action plans for restoring naturally pristine air in their national parks and wilderness areas by 2064. But most have made little progress toward that goal, the report says.

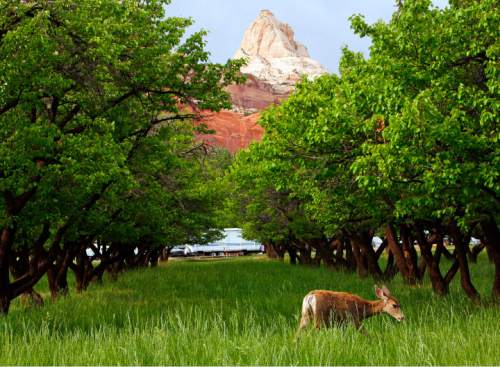

Pollution at Zion cuts visitors' views by an average of 46 miles, Miller said. The park has also documented increased temperatures the past several years.

Zion, like many of Utah's other parks, also struggles with ozone levels, which can cause problems for visitors with asthma or other respiratory conditions. And, the report points out, ozone levels tend to peak at the same time as the parks' visitation — in mid- to late summer.

Like so many unsolved environmental puzzles, the situation in Utah's parks is complicated. The root of the problem isn't the number of cars being driven around within the parks, said Ulla Reeves, the NPCA's clean-air program manager — although that is a factor, too.

"It's not just about what happens in the parks," she said, "but what happens in the park airshed."

In Utah, Reeves said, research has clearly demonstrated that all five of the state's national parks share an airshed with the state's primary source of electricity — Rocky Mountain Power's Huntington and Hunter coal-fired power plants outside Price.

A recent Sierra Club analysis found that those two plants alone contribute significantly to air pollution, producing as much as 40 percent of the state's nitrogen oxide, said Shane Levy, deputy press secretary for the Sierra Club.

"Unfortunately, earlier this year, the state put forth a proposal that would give a pass to big polluters by unfairly allowing the Hunter and Huntington coal-fired power plants to continue to dump dangerous haze-causing pollution into our air without having to clean up those emissions," he said.

"Coal plants in Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico have already installed state-of-the-art pollution controls, showing that this technology provides common sense, cost-effective ways to reduce emissions that put public health and clean air at risk."

The state's move to take credit for the 2015 closure of Rocky Mountain Power's Carbon coal-fired plant is a sore spot for the NPCA as well. Cory MacNulty, a regional program manager, said the state had tried to trade credit for the closure for requirements that would force the remaining plants to install upgraded pollution controls.

"The technology we're asking for," she said, "is already used across the country."