This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Perhaps Mother Nature was weeping for joy — although critics likely believe she shed tears for a different reason.

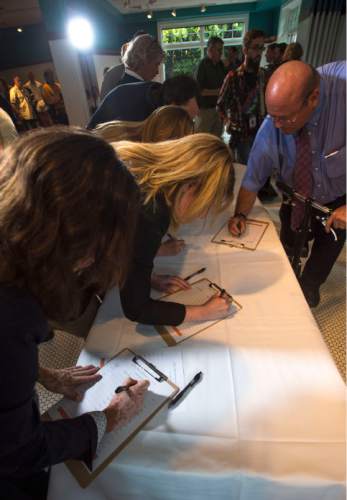

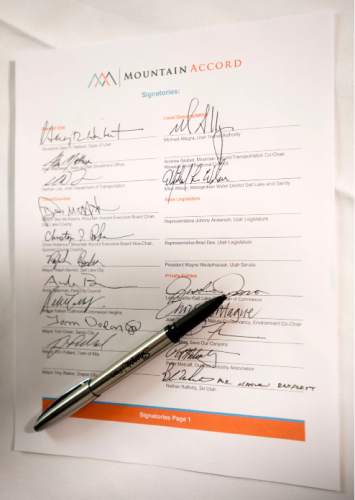

As a downpour moved planned outdoor ceremonies at the mouth of Big Cottonwood Canyon indoors Monday, leaders from cities, counties, the state, ski resorts and environmental groups signed the "Mountain Accord," which outlines the ways to preserve the Wasatch Front canyons.

"We brought together all the important groups that care about the central Wasatch Mountains, and we put ink on paper [to outline] a plan to save the Wasatch Mountains well into the future," said Mountain Accord coordinator Laynee Jones.

"No urban area in this nation has such a phenomenal asset," Salt Lake City Mayor Ralph Becker said of the mountains. "We have, through the Mountain Accord, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to protect, to prosper from, and solve transportation issues for our mountains and our communities."

The document represents a consensus among organizations that worked on it — although they say it is not perfect, nor even legally binding. But it is a public statement agreeing to protect sensitive canyon environment and watershed.

Some important parts:

• Ski resorts in the canyons are forgoing possible future ski-area mountainside expansion in exchange for land swaps designed to help them better develop their base areas in canyon bottoms. The accord details those plans.

• It asks Utah's congressional delegation to help create a "national conservation and recreation area" that specifically prohibits "expansion of ski areas onto public lands beyond the resort-area boundaries."

• The document serves as a starting point for a comprehensive environmental impact study that the U.S. Forest Service and the Federal Highway Administration are expected to undertake, as Jones said, to help "execute the conservation and preservation plan and tackle transportation" issues.

Plenty of controversial issues remain undecided that would be addressed by that environmental study.

They include the idea of putting rail service up Little Cottonwood Canyon, cutting a tunnel to link the tops of Big and Little Cottonwood canyons, or finding some combination to create a "One Wasatch" interconnect between all seven area resorts.

"As our population grows … we risk loving our central Wasatch to death, and that cannot happen," said Salt Lake County Mayor Ben McAdams. He called the accord "a generational decision and road map for how we are going to protect and preserve our central Wasatch for future generations."

Summit County Council member Chris Robinson called the Wasatch mountains a "crown jewel" and said the accord "really respects the disparate groups" that helped write it. "This is the best of government and private parties working together. ... The real work begins as we start into this second phase" of environmental study.

Gov. Gary Herbert said bringing together all the interests to talk about canyon plans is important as Utah grows rapidly. "This is an unprecedented partnership of stakeholders coming together."

Not everyone is happy.

For example, Pat Shea, former director of the U.S. Bureau of Land Management who is now a lawyer working with Friends of Alta, was at the ceremony passing out fliers saying that Little Cottonwood Canyon "does NOT need a tunnel or a train!"

While he praised the accord process, Shea said, "There are financial interests that are driving an agenda that is too expensive and ecologically unsustainable. And that's the tunnel and the train. We should have a bus system, and we should not have private cars lining the canyon."

George Chapman, a Salt Lake City mayoral candidate, was at the ceremony to oppose key parts of the accord — also criticizing potential rail and tunnel systems, and creation of the national conservation area to limit ski-area development.

McAdams said the accord signers tried to listen to all interested parties and find a consensus.

He said it is the product of "dozens and dozens of public hearings, and thousands of public comments. ... I would say there is no decision in Utah that has been made with as much public input and engagement as this Mountain Accord today. It is truly an open and transparent process. It is model for future processes."

Herbert also called the accord "an amazing document. It's comprehensive in its scope, and with specificity that gives us a great outline of how we can move forward here to accommodate the challenges we face as a fast-growing state."