This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

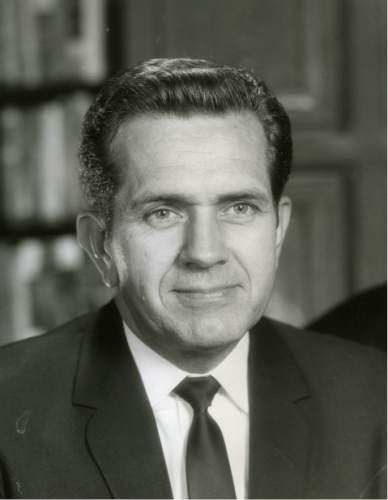

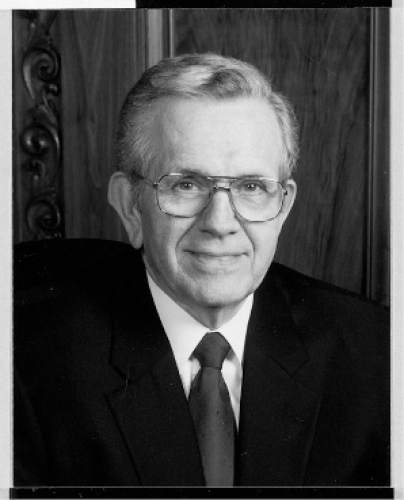

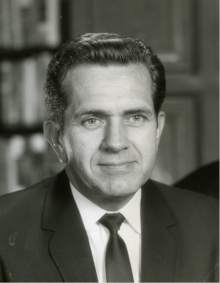

Longtime Mormon apostle Boyd K. Packer seemed a man of contradictions.

He was an educator who was wary of intellectuals, a theological purist who spoke more candidly about sexual issues than most LDS authorities, a sometimes-stern speaker from the pulpit who tended to be lighthearted, witty and playful at home, and a tough-talking administrator who spent his off-hours carving birds and ducks out of wood.

Packer — who died at about 2 p.m. Friday at home at age 90 after serving more than 45 years as an apostle and rising to within a breath of leading the worldwide faith — was not, as many thought, a black-and-white kind of guy.

His death leaves fellow apostle Russell M. Nelson, also 90 and a renowned heart surgeon before he entered full-time LDS Church service, as next in line for the presidency after 87-year-old President Thomas S. Monson.

Packer's passing also comes barely a month after the death of longtime colleague L. Tom Perry, 92, leaving two vacancies in the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.

The three-member First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve together make up the top two ruling councils of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

"The lessons that he's taught are long in the hearts of people and in their minds," his son Allan Packer, a member of the LDS Quorum of the Seventy, said in a statement.

Details for funeral arrangements are pending, the church said.

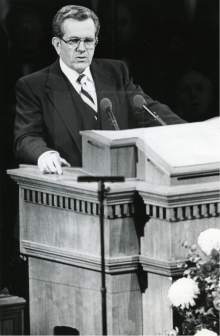

Boyd K. Packer gave some of the boldest, most rigid speeches Mormons had ever heard. He tackled difficult topics — from masturbation ("do not be guilty of tampering with this sacred power of creation") to homosexuality ("any persuasion to enter into any relationship that is not in harmony with the principles of the gospel must be wrong") to the faithful writing of LDS history ("there is no such thing as an accurate, objective history of the church without consideration of the spiritual powers that attend this work").

In the 1990s, he pointed to gays, feminists and intellectuals as the greatest threats to the expanding faith. In 2010, he caused an uproar when he preached that gays can resist the urge to act on their attractions and suggested they could change their sexual orientation. And, in 2013, he lamented the "weakening of the laws of the land to tolerate legalized acts of immorality" and warned Mormons to beware of the "tolerance trap."

But the vast majority of Packer's sermons — he gave more than 100 General Conference addresses — dealt with fundamental Christian themes: faith, baptism, spirituality, forgiveness and the atonement. His addresses rang with eloquence. He chose his words carefully, like he did the splashes of color in his paintings.

"If you have festering sores, a grudge, some bitterness, disappointment, or jealousy, get hold of yourself," Packer said in a 1977 speech. "You may need a transfusion of spiritual strength to be able to do this. Then just ask for it. Prayer is powerful, spiritual medicine."

Like all Mormon apostles, Packer traveled the globe, meeting with members, missionaries and potential converts. He worked on the edition of the church's scriptures in the 1970s, making sure to add changes suggested by LDS founder Joseph Smith as well as extensive study aids. He was involved in overseeing the first computerized edition of these texts in 1988. And, in the fall of 2012, he dedicated a Mormon temple in his hometown of Brigham City on a site where he once attended grade school.

Members of his large clan — 10 children and scores of nieces, nephews, grandchildren and great-grandchildren — knew him as a great teacher and loving family man with an extraordinary work ethic and a lively sense of humor.

"I'm three-fourths Danish," Packer told documentary filmmaker Helen Whitney. "That accounts for my being resolute, which is a better word than stubborn."

—

Bucolic beginnings • Boyd Kenneth Packer was born Sept. 10, 1924, in Brigham City, the 10th of Ira and Emma Packer's 11 children.

His father was a mechanic, who eventually built a car dealership. At age 5, young Boyd was laid up for six weeks with what was diagnosed as pneumonia, but later determined to be polio. He was confined to his bed, mostly unable to move. When he finally recovered, he struggled to learn to walk again.

That experience took a toll. In photographs taken after the illness, according to Packer biographer Lucile Tate, there was "an old look in a young face."

Inner fear "became a reality to be reckoned with and eventually overcome," Tate writes. "Fear finally left Boyd, but the feeling of inadequacy persisted."

He couldn't run and play sports. Instead, he developed a keen eye for detail and an ability to re-create images from nature. He crafted miniature farm, circus and jungle animals as family gifts.

A deep love of birds took root. He belonged to a Brigham City pigeon club, Tate writes, whose members offered their homing pigeons to distribute and collect votes from far-flung Utah communities in the 1938 elections. Once in awhile, the wild birds would make a home in the spires of the Box Elder Tabernacle.

To retrieve them, Boyd and a friend would jimmy a window, climb to the attic, crawl on the catwalk, and then inch up to the top of the spire, the biographer explains. These became Boyd's twin qualities — love of birds and fearlessness in the face of danger — that stretched into adulthood.

—

Military and marriage • World War II prevented Packer from serving a Mormon mission after high school. So he enlisted in the military and was a 21-year-old bomber pilot in Okinawa during the war's final days. While standing on a beach in Japan, Packer decided to become a teacher.

After returning to Utah, he met and married Donna Smith, a beauty queen. He then graduated from Utah State University with a degree in education.

While working on a master's degree there, he also taught in the LDS Church Educational System (CES), including opening the first American Indian seminary. For four years, he served on the Brigham City Council as a Democrat — the party of many in the Packer clan, said Packer's nephew, Lynn Packer.

The seminary experience pushed Packer's career away from university education and toward teaching religion, which he did with such gusto it attracted the attention of LDS leaders. In 1961, at age 37, the seminary teacher became an assistant to the Quorum of Twelve Apostles, a full-time church position, and was tapped to help supervise CES while he still was completing a doctorate in education at Brigham Young University.

Packer and his friend A. Theodore Tuttle, who would become a member of the Utah-based faith's First Quorum of the Seventy, were determined to stop a secular movement within CES. Some of the church's teachers had been trained at the University of Chicago, and they wanted the system to be similar, except with a Mormon bent.

Packer and Tuttle saw such a movement as a sellout, trading faith for academic credentials.

Within four years of his assignment to full-time church service, Packer was sent into a hotbed of the 1960s anti-war movement, Cambridge, Mass., as president of the church's New England Mission.

"President Packer was driven by the work, by doing God's will, that was paramount,'' said Scott Kenney, one of his missionaries from Alpine.

If a missionary had a problem, Kenney said, the key question for Packer was not how to help the individual but how to forward the work.

Packer's predecessor was the late Truman G. Madsen, a garrulous intellectual who taught philosophy at BYU until his death in 2009.

"Truman sent some missionaries to counseling. Elder Packer sent none. Truman had several missionwide fasts, Elder Packer had none," Kenney said. "Truman urged us to teach by the spirit. Elder Packer said get out the door and teach."

Packer's style was a form of "tough love,'' pushing young people into peak performance, Kenney said. "No one suffered unduly because of his approach.''

Under Packer's leadership, the Boston LDS Stake, a group of Mormon congregations, started an early-morning seminary program for LDS high-schoolers. He also launched religious education for college-age Mormons and taught several classes himself.

—

Watchman on the tower • Soon after his return to Utah, Packer was called to the Quorum of Twelve Apostles in 1970 . He felt overwhelmed, observers say. That feeling of inadequacy never left, but neither did his determination to do all he could to further what he saw as God's kingdom on Earth.

"Ever present is the sure conviction," he said in 1985, "that the call to this sacred circle of brethren comes from the Lord.''

Tate called her biography, "A Watchman on the Tower," alluding to a biblical passage urging believers to be on the lookout for approaching enemies, which speaks to Packer's self-perception. The young apostle came to see his role as keeping the church pure from outside influences and to warn the members, especially young people, of the threats around them.

The world's values are "spiritual crocodiles," Packer once said, dangerous ideas that "you can't see that are lying in the mud ... to grab you."

Packer didn't always relish the role of straight shooter on delicate issues, but he didn't shrink from the task either.

He initially balked when then-President Spencer W. Kimball asked him to address male sexuality, including homosexuality, at a BYU fireside in March 1978, according to the second volume of Edward Kimball's biography of his father.

"But after soul-searching," Edward Kimball writes, "he decided he could not refuse 'an assignment from the prophet.' "

Lynn Packer remembers going to eat with his uncle at the Church Office Building in Salt Lake City before that speech. The apostle had only water, Lynn Packer recalled, saying he was "too nervous to eat."

In a 1976 General Conference address, Packer discussed masturbation, using the euphemism "little factories" to describe male anatomy.

"This little factory moves quietly into operation as a normal and expected pattern of growth that begins to produce the life-giving substance. It will do so perhaps as long as you live. ... For the most part, unless you tamper with it, you will hardly be aware that it is working at all," Packer said. "As you move closer to manhood, this little factory will sometimes produce an oversupply of this substance. The Lord has provided a way for that to be released. It will happen without any help or without any resistance from you. Perhaps one night you will have a dream. In the course of it the release valve that controls the factory will open and release all that is excess."

The speech prompted amused chatter, but later was reproduced in a pamphlet for use by the church's youth leaders.

"It was his really sincere attempt," Lynn Packer said, "to address an issue that most general authorities wouldn't touch."

His October 2010 General Conference speech, suggesting that gays could change their sexual orientation, drew more than chuckles. It sparked petitions and protests. Within days, Packer, by then president of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles and next in line to lead the LDS Church, modified his speech to align more closely with his faith's view that the cause of same-sex attraction is unknown and that the only sin is acting on those desires.

In April 2013, Packer again raised eyebrows with a hard-edged sermon about the rise of immorality and the nation's acceptance of it. He did not mention gay marriage, but his remarks came in the wake of public-opinion polls showing a dramatic swing in favor of recognizing same-sex unions.

"Tolerance is a virtue, but, like all virtues, when exaggerated it transforms itself into a vice," said the apostle, speaking from his chair rather than from the pulpit as became common in his later years. "We need to be careful of the 'tolerance trap' so that we are not swallowed up in it."

Just last month, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling legalizing same-sex marriage in all 50 states.

At one point, Packer tried to soften the apparent harshness of his remarks about feminists and intellectuals.

"I don't remember saying those things. But if it's in print, I said it," Packer told filmmaker Whitney, almost apologetically.

Maxine Hanks — a Mormon feminist and one of the so-called "September Six" excommunicated from the LDS Church in 1993 — recalled letters she exchanged with Packer a year after she rejoined the faith in 2012.

"I wrote to him in 2013, to revisit and resolve issues from 1993 — by honoring both my work and his, affirming my sincere intent of feminist research, while admitting that I likely caused him some stress," Hanks said Friday in an email.

The apostle replied, according to Hanks, "I appreciate the sincerity of your feelings and the spirit in which they were written. Know that for my part, I have only admiration and joy to know of your progress and growth."

Those words moved Hanks, she said, "since it referred to my efforts past and present, not just my return to the church."

—

A different view • Even Mormons who have disagreed with Packer say they have seen his spiritual love in action.

Consider his work in the early 1970s with the Genesis Group, a small monthly gathering of black Mormons. Its purpose was to support these black families, including men, who at the time were barred from the faith's all-male priesthood, and their wives and children who couldn't enter LDS temples.

Once, when Genesis leaders tried to enter the Mormon Tabernacle for the priesthood session of General Conference, an usher barred the black men from the door. Darius Gray, one of the Genesis leaders, said they sent an urgent message to Packer, who told the stunned volunteer to escort them into the building and show them to their seats near him on the stand.

In June 1978, Packer was in the Salt Lake LDS Temple when Spencer Kimball and all 15 top members of the hierarchy agreed to lift the priesthood ban. Packer was one of three apostles charged with proposing a course of action for making the announcement. He immediately called the Genesis leaders and offered to ordain them.

"I know of some of the issues that have troubled others, but as I have listened to and pored over his conference addresses, I have found nothing but good," Gray said. "I am grateful for my association with him and for his influence in the world."

—

Ideas are crucial • Packer was "a true intellectual, more even than I am," said Mormon historian Richard Bushman, one of the church's premier thinkers who has taught at Columbia, Boston University and Claremont Graduate University in Southern California. "He thinks ideas are very, very important. That's why he worried so much about them."

Bushman became acquainted with Packer at BYU, where the historian was teaching in the 1960s. Their paths crossed again when Bushman was teaching at Boston University and Packer became an LDS mission president in the region.

Decades later, Bushman asked for — and received — a blessing from Packer as the historian commenced work on "Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling," his critically acclaimed magnum opus on the LDS founder.

Though a lifelong Mormon, Bushman knew he would have to include unflattering, even challenging aspects about the faith's first prophet if his book were to have any credibility in the world outside Mormondom.

Packer offered a powerful prayer, Bushman recalled. "It was a lovely experience. He's a very spiritual person who strives harder than most others to listen to God's spirit as it comes to him."

The apostle never told the historian how to write the book nor has he offered a single negative word about the finished volume, Bushman said. "He allowed me to do it in my own way."

Marlin K. Jensen, an emeritus Seventy and former LDS Church historian, called Packer a "complex and extraordinary man."

"Misunderstood by some, he always impressed me as being compassionate and caring," Jensen said. "He cared about the impact of the church's programs and costs on the ordinary member. He cared about missionary work (overseeing a major program revision in 1985), genealogy (helping change it to family history), and the temple (his book "The Holy Temple" is widely read).

"He cared about the church's canon of scripture, its music, its history, its doctrines," Jensen added. "He cared deeply about the institution of the family. ... He was one of the most powerful and effective apostolic witnesses and teachers."

—

The art of raising kids • It's no understatement to say Packer's family was his greatest joy. The children were reared in a big house in Sandy, surrounded by much untamed property. Wild animals — mostly exotic birds, including peacocks — ran free and were available for object lessons.

Once a neighbor approached Packer, saying he noticed the kids weren't too successful farming their father's land. He offered to help out and then split the profits with the apostle.

Packer countered — or so the story goes — "you forget, I'm raising kids, not crops."

He often gave his children practical gifts: toolboxes, paintbrushes, shovels. On one side of the house was a workshop, where parents or children could tackle large projects.

During the apostles' traditional July break, Packer always had a project — build a shed or fence, dig a pond, repair a car. He taught himself WordPerfect. He took up bird-watching and learning new languages. He sculpted or painted pictures, some of which made up his 2004 exhibit at the Museum of Church History and Art, "Lifework of an Amateur Artist." He illustrated his 1975 ode to education "Teach Ye Diligently."

Packer summed up his assessment of any life, including his own, in the conclusion of his 1993 book, "A Christmas Parable."

"Only when the fabric of life is torn will we look inside of ourselves; there to find who we are, who [Christ] is, and what gift he offers us," the apostle wrote. "Then each may follow his own star to Bethlehem and kneel there to worship.''

David Noyce and Michael McFall contributed to this report.

Twitter: @religiongal