This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

During a particularly upbeat cabinet meeting not long after the Pac-12 invited Utah to join the conference, athletic director Chris Hill tried to sober U. leaders with the thought that they'd soon share the room with a coach who earned more than $2 million per year.

That $16 million football center the U. had planned to build? It needed to be a $34 million football center.

They'd also need to hire new employees — roughly 40, to date.

Everything, down to the printing, postage and linen service — which combine for more than $530,000 in the most recent budget — needed to be on par with 11 schools that spent more freely.

"When we were in the Mountain West, you have one set of needs, and if you get in the Pac-12, you have another set," said coach Kyle Whittingham, who, indeed, will make at least $2.6 million in 2015.

It's been five years since the arrival of the supposed golden ticket. Utah now receives a full share of league revenues after three years with a thinner slice, and the department is fresh off a banner season in which seven teams finished ranked.

Things are looking up. But margins remain thin.

There are 64 teams in the nation's wealthiest five conferences, known colloquially as the Power Five. Fifty-two schools are public, and when ordered by USA Today and Indiana's National Sports Journalism Center each year, they're required to provide the revenue and expense reports they send to the NCAA.

Of those 52, in 2014, Utah ranked 51st in total revenue and 52nd in expenses.

Utah received a 75 percent share of conference revenues in 2014 — $5 million less than other conference teams — but its total revenue would have been 51st even with a 100 percent share. No. 50 Mississippi State earned $5.8 million more.

It may not be as disadvantaged as all that, though. Utah turned a small profit — a little less than $1 million after $4.5 million repayment of university debt and facility support that is not reflected in USA Today's database — unlike Washington State, which spent $13.7 million more than it made.

The 2015-16 budget will likely show plateauing expenses. The department borrowed $7 million from the university during its first three years of Pac-12 membership, Hill said, and Utah hopes it won't be in the red for long.

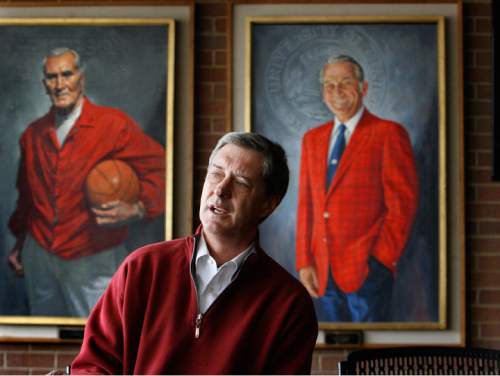

"We never, in my time, have never been in the hole with our fund balance," Hill said. "But we said we can wait two, three, four years to improve our program, or we can invest some now."

Utah's Steve Smith — Utah's other Steve Smith — has served in the business office since 2005 and is the department's CFO. He's seen total revenues grow from $25.5 million in 2005 to $56.5 million in 2014 (and more than $62 million in Fiscal Year 2015), and he's seen expenses grow just as fast.

"Going forward, we're now going to be kind of flat," Smith said.

That's a real trick.

Salaries for FBS football coaches increased 75 percent over seven years, according to a Newsday report, and Whittingham's recent extension was followed by a new deal for Larry Krystkowiak that made him one of the Pac-12's highest-paid men's basketball coaches. The football center may be built and a $36 million basketball facility may be nearing completion, but the department isn't done paying for either.

The highest percentage increase on Utah's budget between 2011 and 2014 was for support staff: from $5.8 million to $10.3 million.

Hill said that, for example, the women's soccer team had a graduate assistant working as its trainer, while every other Pac-12 team employed a full-time trainer: "You don't want Mom and Dad going on a visit, and school X in the Pac-12 says, 'Hey, I know we're recruiting against Utah, but they don't even have a trainer for your team.' "

Such hires add up. Among them: learning specialists; commission ticket salesmen; a facility manager; a receptionist; directors of personnel for football, basketball and gymnastics; plus additional staffers for game management, social media, video production, business, strength and conditioning, IT, insurance, compliance, nutrition, sports information and wellness.

A part-time groundskeeper was promoted to full time, as was a part-time ski coach.

And so on.

Hill said that most positions are entry level, and "I'm not proud of this, but our support staff and entry-level people get paid less than most people in the league" — a factor he attributes partly to high interest in living in low-cost Salt Lake City.

Upper-level staffing has not increased, he said, though salaries have.

An unforeseen challenge has been reacting to NCAA deregulation that allows Utah to provide more for its student-athletes.

Lessened restrictions on meals added between $300,000 and $400,000 to Utah's budget last year. This year, cost of attendance stipends will tack on $1 million.

Other surprises have been few, but Hill and Smith acknowledge thinking Pac-12 Networks would have struck a deal with DirecTV by now.

It was also strange under the Pac-12's equal sharing model to realize Utah would be penalized financially for making a bowl game, though those are checks they'll happily write.

The goal now is to boost salaries and facilities for some of the school's nonrevenue teams. And to continue the success of the moneymaking sports. And to pay down debt.

The Pac-12 is giving them more, yes. But they can use every penny.

mpiper@sltrib.com Twitter: @matthew_piper