This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

It was a year ago that Sean Kendall learned the grim news that his dog — his best friend — had been fatally shot by a Salt Lake City police officer.

Kendall was at his job June 18, 2014, when an animal control officer's phone call interrupted his work — and life.

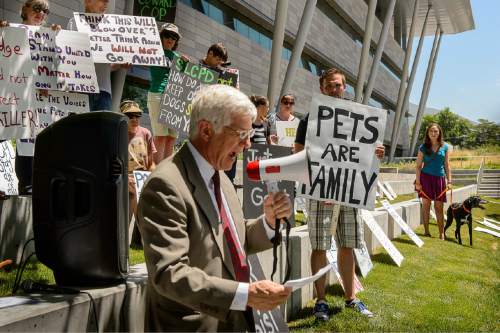

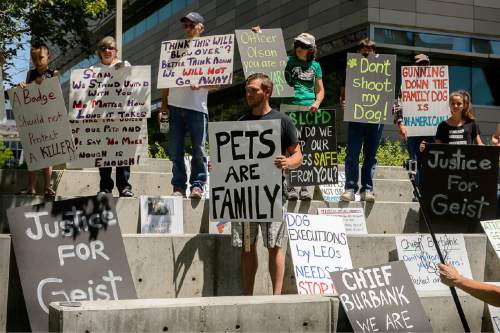

The 28-year-old recalled those events at a demonstration Thursday, the first anniversary of the death of his 2-year-old Weimaraner, Geist, held outside the Salt Lake City Public Safety Building.

About 30 protesters attended the rally, holding signs that read "Justice for Geist" and "Man's best friend should not be gunned down."

"What killed Geist is exactly the same thing killing people," said Edward Peltekian, of Salt Lake City. "Enough is enough. Stop killing people. Stop killing animals."

Former Salt Lake City Mayor Rocky Anderson, an attorney who is representing Kendall, attended the rally with his dog, Teddy, and also spoke.

"This matter is all about accountability," Anderson said. "Do we allow any governmental official, whether police or members of the [Mayor Ralph] Becker administration, to violate the Constitution, to enter our homes, our yards, to use legal force against those in our community, including our beloved dogs? The buck stops with the mayor."

Anderson also criticized Salt Lake City council members for the lack of policies concerning police contact with dogs.

"The city council talks a good talk, but they have done nothing to make certain that we have in place the policies, the training and the procedures to make sure this doesn't happen again," Anderson said.

"We should be a shining example for the nation, instead of falling in line with the pattern of police brutality," said Anderson, who reactivated his law license to represent Kendall.

"One year ago, my life completely changed for the worse. I will do whatever I can to make sure no one has to go through what we went through." Kendall told the crowd.

The shooting took place in Kendall's fenced-in backyard as Brett Olsen and other officers searched for a missing 3-year-old boy who was later found asleep in his own basement.

Olsen went into Kendall's yard to look for the boy, he said, and Geist barked and ran toward him. When the dog was about 10 feet away, Olsen grabbed his pistol, and fired when Geist was about 4 feet away, according to a report by the Police Civilian Review Board, which found that Olsen — acting under "exigent circumstances" — violated no department policies.

The Salt Lake City Police Department also found that Olsen "acted within policy" when he shot the dog.

Kendall notified the city in January that he intends to sue for $1.5 million over the dog's death, though he has yet to file a lawsuit in either district or federal court. He has filed papers in district court challenging a bond statute, which requires a person suing a law enforcement officer to post a bond before a complaint is filed that is large enough to guarantee payment of all costs and attorney fees.

Anderson wrote in court papers that his client can't afford to post the required bond, and that the statute violates Kendall's rights, including his right of access to courts. A judge has yet to rule on the matter.

Christina Judd, director of public relations for the Salt Lake City Police Department, said Thursday she could not comment on pending litigation.

Kendall last year turned down the police department's offer to pay him $10,000 to compensate him for his pet, saying he wouldn't be satisfied until the department changed its policies on using force against dogs.

He says the police department does not adequately train officers to deal with dogs, and that Olsen violated his Fourth Amendment rights by entering his property without sufficient cause.

In March, Utah's police academy announced it will begin a pilot program to teach future officers how to interact with pet dogs. The Utah Peace Officer Standards and Training Council approved a plan to train cadets on dog behavior, encountering hostile dogs and alternatives to use of force. If the pilot program is successful, it could be expanded to police training programs across the state, officials said.

Cheryl Stout, an advocate for animal rights who attended Thursday's demonstration, said Kendall's rights were violated.

"I'm terrified that my dog may not be safe in her own yard," Stout said. "That someone can come in my yard without a reason and kill my dog. When I saw Geist — I saw my dog."

"Nobody's going to forget about Geist until justice is done," Anderson said.

— Tribune reporter Jessica Miller contributed to this story