This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

For Yvette Bugingo, Ethiopia is home — as much as any resting spot for a refugee can be called "home."

Born in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and forced to flee at 11 when her father was killed, Bugingo spent most of her childhood in northeast Africa, studying English, converting to the Mormon faith, waiting for her life in a better place to start.

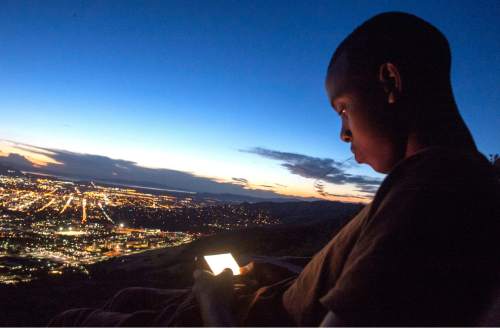

Now, seven years later, Bugingo is learning to call Salt Lake City home.

Bugingo, her mother Godelive, sisters Ines and Alia and brother Philip arrived last summer. They've scrambled to find housing and jobs and enroll in school. Now, five months later, the family is trying to catch its breath.

"I guess everyone is doing good," 18-year-old Yvette said. "We've got to get used to the cold now."

The Bugingos are among the roughly 60,000 displaced people who call Utah home. Each year, 1,100 more refugees settle in Utah, according to Gerald Brown, director of Utah's Refugee Services Office, a division of the Department of Workforce Services.

First it was families from southeast Asia fleeing the Vietnam War. Then Bosnians, Serbs and Croats escaped ethnic violence in the former Yugoslavia. Then exiles from Burma found refuge in Utah. And finally, refugees from Africa — the Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia — have started settling in the Intermountain West.

The state's refugee numbers are fluid, and change as exiles become U.S. citizens, eventually adopting their native country and moving beyond the crisis stage of resettlement. At that point, the state stops counting them.

Getting to the point of citizenship, however, is a long, difficult road — of menial jobs and English classes and remedial education in some cases.

Refugees, Brown says, are survivors. Their successful transition to life in American is more than an exercise in self-preservation — their unique talents and cultural history benefit Utah as well.

"You don't get here by being stupid," he said. "All of them are survivors. They have the potential to be tremendous assets to our community, but to become assets we've got to welcome them and we've got to give them a hand up."

Out of Africa

The Bugingos don't talk much about their life before Ethiopia.

After years of schooling in Ethiopia, the children speak fluent English. Settled into a spartan Salt Lake City apartment filled with bargain furniture, they are articulate, jovial and brimming with warm smiles.

But questions about their life in Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) prompt uncharacteristically guarded responses.

Yvette remembers the country of her birth being beautiful and full of animals. Her parents didn't talk much about the dangers surrounding them, but even as a child she was aware that her family wasn't safe.

"It's home, but it wasn't home," she said. "I was born there and I know my family is from there, but the country doesn't feel like home because of all that happened."

The DRC has seen decades of war and conflict, which have cost the lives of millions of Congolese. In 2013, the country was ranked 186 out of 187 countries on the Human Development Index, a report that combines statistics including average life expectancy, education levels and income.

Ignace Bugingo, the family's patriarch, was killed in 2007. And six years of flight started.

"That's the reason why we basically fled from the country," 21-year-old Ines said.

Godelive Bugingo and her four children left DRC in November of 2007, traveling by bus, truck and taxi through Uganda and Kenya before arriving in Ethiopia in January of 2008.

Police in Kenya took all of their possessions, so by the time the traumatized family arrived in Ethiopia, they were entirely dependent on help from the United Nations.

"Refugees are not allowed to have citizenship in Ethiopia so you can't work or do anything," Ines said. "You can still go to school, but it's hard."

The family was fortunate to avoid being placed in a refugee camp, where living conditions are miserable with little water, no power and snakes.

Instead, the Bugingos were placed in an urban refugee program that provided money for schooling and housing after Alia, then a toddler, became sick. Her illness spared them from living for years in the camps.

"After looking at Alia, that's when [a U.N. staffer] decided that we'd stay in the city," Ines Bugingo said. "Everybody would tell you about the camp and you're just like, 'How can I survive there?' I wasn't glad that she was sick, but then, I don't know."

In 2011, the family was almost relocated to the United Kingdom, but the move fell through.

A year later, they joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints after a friend and fellow refugee invited them to visit.

Then in April of 2013, the Bugingos learned they could resettle in the United States. They were allowed to choose from a list of about a dozen metropolitan areas, including Salt Lake City. They picked Utah.

Even after that decision was made, the family was left waiting for more than a year before finally arriving in July of this year.

The Bugingos settled in a Rose Park apartment complex that is home to a melting pot of other refugees from Ethiopia and other countries.

"A tough row to hoe"

Brown said there are unique aspects to the refugee experience that don't always apply to other families struggling to get by.

Many refugees do not speak English, he said, and all refugees have experienced persecution in their home countries.

But he also said that because refugees are brought to the country, they typically lack the support systems that many immigrants find when they arrive in the United States.

"People that decide to come here often have stuff waiting for them, like family or friends to help them," Brown said. "Refugees don't."

Refugees also are required to pay the government back for their travel costs, Brown said, meaning they are in debt before they even set foot on American soil. That requirement likely was established to make the United States Refugee Admissions Program more politically palatable when it was created in 1975.

"My guess is they thought the public would support it more if they knew the people were paying back their airfare," he said.

Incoming refugees receive a one-time payment of roughly $1,100 from the State Department that typically goes toward setting up housing, Brown said. After that, the Office of Refugee Resettlement provides medical screenings and some financial assistance if an individual does not qualify for mainstream welfare services.

"If they can't get a job and they're a single adult, for example, then they will get eight months of support," Brown said. "But after eight months, that's done."

Finding a job presents another challenge, Brown said. Because many refugees lack formal job training, it is typical for individuals to take low-wage jobs that require at least two workers to support a household. As a result, many young adults are forced to choose between pursuing an education or contributing to the support of their families.

"People don't pick themselves up by their bootstraps unless they can get educated one way or another," Brown said.

But even highly-skilled workers can see their credentials nullified due to inconstancies between their home country's education requirements and technology and those in the United States.

"We get Iraqi engineers, Iraqi dentists, and they come and they realize it's going to be a tough row to hoe before they can practice their profession here," Brown said.

Godelive Bugingo graduated from a mechanics course in Ethiopia but is not currently working. She attends English classes through Granite Peaks Lifelong Learning, an adult education program administered by Granite School District.

English is Godileve's fifth language, after French, Swahili, Kinyarwanda and Amharic.

"I study," she said. "I try. I try."

Brown said more than anything, successful integration requires a welcome from the community a family resides in.

"Refugees need friends," he said. "They need people to come up to them and be nice to them. That's more important than any program that we can come up with."

Parting ways

When they arrived, Ines and Yvette quickly found work at a hotel in Park City. They worked through August and September but were let go for the slow period between the summer and winter seasons.

Neither sister misses those jobs, however, or the commute from Salt Lake City.

"We had to travel like three hours every day, going there and coming back," Yvette said. "Pretty much what it meant was no school and working there every night."

Now, they are focused on education.

Yvette works at Blue Nile, an Ethiopian restaurant, and recently completed a free GED prep program at Stevens-Henegar College. She said she plans on taking the GED after Thanksgiving and hopes to enroll at LDS Business College in the spring.

"I would love to work in any humanitarian sort of job because I want to go back and help," she said. "I don't have anything started right now, but that's what I hope to be able to do in the future."

Ines currently is looking for work. She is close to earning a high school diploma through an adult education program offered by Horizonte Instruction and Training Center.

Kevin Miller, director of Salt Lake Community College's student conduct and support services, said the program is targeted toward first-generation college students. The courses are taught by Horizonte instructors, he said, but students meet on the SLCC campus and have access to the college's resources.

"That really is the intent of all of these programs," Miller said, "bringing those high school students on campus to give them a leg up on getting familiar with what college is about."

Ines received a scholarship to pursue an associate degree and hopes to study international business. She's still weighing her options, but her top choice of schools would be LDS Church-owned Brigham Young University.

"I've always wanted to go to BYU," she said.

While BYU doesn't track how many refugee students are on campus, spokesman Joe Hadfield said admissions staff will take a potential student's background into account when reading their application essay.

"They look for some of those things that might stand out that this is a student who is deserving and ready," he said.

The younger Bugingo kids also are in school: 8-year-old Alia attends North Star Elementary and 16-year-old Philip Bugingo is a sophomore at West High School.

Philip's favorite class at West High School is LDS seminary.

"It's fun and you have freedom and you're talking about church," he said.

Meanwhile, their mother is making friends. Yvette said there are four other families from Africa at the complex, so her mother has "homies" to hang out with.

The family will spend Thanksgiving and Christmas with returned Mormon missionaries who met the family in Africa.

Utah, Yvette says, is beginning to feel like home.

It will be strange if her older sister moves to Provo to attend school. But, Yvette figures, it's inevitable that her siblings will eventually set out on their own.

"We've shared a room since I was born," she said. "It will be a little weird, but I guess there comes a time when everybody needs to leave."

bwood@sltrib.com Utah's refugee population

Vietnamese: 14,000 people

Iraqi: 6,000 people

Somali: 6,000 people

Sudanese: 6,000 people

Bosnian: 6,000 people

Total: 60,000 people

*numbers are approximate

Source: Refugee Services Office, Department of Workforce Services